South China Morning Post / Winston Mok / Sep 9, 2020

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3100608/why-nokia-or-ericsson-might-be-wests-best-bet-against-huawei

The US has continued to pressure countries around the world not to use Huawei equipment in their 5G networks. When Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s talking head is the US’ key competitive weapon against Huawei, something is not quite right.

While the US government is fighting Huawei today, earlier in the last century, it did the opposite – dismembering Western Electric, AT&T’s equipment arm, long before the break-up of AT&T. Its actions led to the creation of two Western Huaweis – Nortel and Alcatel – which became leading competitors of Lucent, the stand-alone American successor of Western Electric.

ITT, a US company which acquired Western Electric’s international operations in 1925, was a key telecoms equipment maker. In the 1960s, through leveraged buyouts, ITT diversified into a range of unrelated businesses, including the Sheraton Hotels chain. Once the largest shareholder of Ericsson, it sold its interests in the company in 1960.

In 1986, an overleveraged ITT sold its telecoms equipment businesses to a French company that would become Alcatel. Meanwhile, the sale of Northern Telecommunications, established by Western Electric to serve the Canadian market, to Bell Canada, resulted in the formation of Nortel.

When Lucent went public in 1996, Alcatel was the world’s largest telecoms equipment company. But in 2006, a struggling Lucent merged with Alcatel; a decade later the combined entity was acquired by Nokia.

More than technological changes and international competition, the fall of the once mighty Lucent may be understood primarily in the American regulatory context and how incentives provided by US capital markets shaped management decisions.

Lucent’s demise was far from inevitable upon its separation from AT&T. Western Electric owed its dominance to being an integral part of AT&T for more than a century. Globally, however, telecoms equipment suppliers usually compete for business outside the umbrella of service providers. Ericsson and Nokia, both from small countries without large service markets, thrive independent from telecoms companies.

More consequential were antitrust actions decades earlier – in 1925 and 1956 when Western Electric’s international and Canadian operations were hived off, resulting in the formation of Nortel and eventually Alcatel which began to compete with Western Electric. Had its limbs not been cut off decades earlier, Western Electric would have been a more dominant global company facing less international competition when it became Lucent.

Lucent, a notable casualty in the dotcom bubble, was a classic case of overextended growth. With aggressive equipment financing, Lucent underwrote a good chunk of capital for new telecoms companies which eventually went bankrupt. Lucent was just as aggressive in engaging in sales and accounting malpractices to deliver “consistent” growth.

Instead of focusing on developing its core products, Lucent spent lavishly on acquisitions which mostly proved to be futile. After the bubble, it made overly drastic cuts to deliver short-term results to the irreparable detriment of its core strengths. Lucent, and ITT earlier, epitomised Anglo-Saxon capitalism’s excesses.

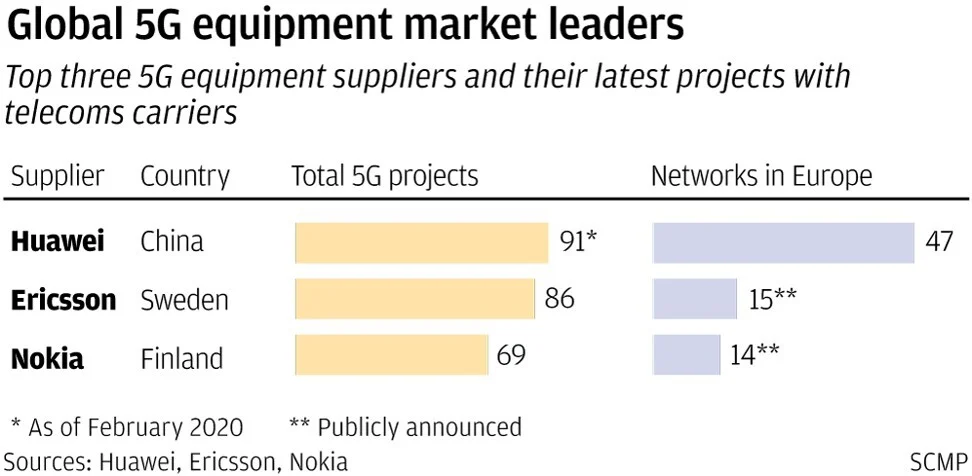

Even though the US lacks a major fully fledged telecoms equipment supplier, it remains a leader in key segments and upstream. Although Huawei may appear to be the global leader in telecoms equipment, market share by segment offers a more useful picture.

For example, Cisco remains the leader in routers. In optical networks, Ciena is a leading competitor. Perhaps, more importantly, the US continues to occupy the top spot in intellectual property, software and chips, through companies such as Qualcomm, Broadcom, Google and Intel. The US can be a much bigger threat to Huawei than the other way around.

Foreign firms’ know-how helped the development of China’s telecoms equipment industry. Technology transfer started with Shanghai Bell, a join venture with Belgium’s Bell Telephone Manufacturing of Belgium, then an ITT subsidiary. Many foreign companies followed suit to gain access to a large and growing market.

Over time, Huawei learned from a range of international peers, through joint ventures with Lucent, Motorola, Siemens and NEC. Nevertheless, the rise of Huawei was probably a contributing factor, rather than the decisive one, in the fall of some of its teachers in the waves of global industry consolidation.

Lucent’s demise is a uniquely American story. The decisions made by its management were shaped by US capital markets which reward short-term results. In contrast, operating in continental European capitalism, Ericsson and Nokia survived the dotcom crisis as they pursued long-term objectives, subject less to the vicissitudes of capital markets. More than competition from dismembered parts of its former self and Huawei, Lucent was destroyed by American capitalism.

From Microsoft to Facebook, Anglo-Saxon capitalism has fostered radical innovations. But it lacks the patience to cultivate incremental innovations over the long term, as the telecoms equipment industry often requires. This patient capital has supported the unrelenting development – through the ups and downs of markets – of the likes of Ericsson and Nokia.

If the US wants Ericsson and Nokia to remain strong Western alternatives to Huawei and ZTE, it would do best to leave them alone, in safe Nordic hands. Otherwise, these last bastions of defence against “Chinese technological domination” may risk perishing under the warped incentives of Anglo-Saxon capitalism.