From CNN

women in sexual professions have always distinguished themselves from other women, from the mores of the time, by pushing the boundaries of style. The most celebrated concubines and courtesans in history set the trends in their respective courts. The great dames of burlesque — Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee — boasted a signature style on- and offstage, reflecting broader-than-life personalities.

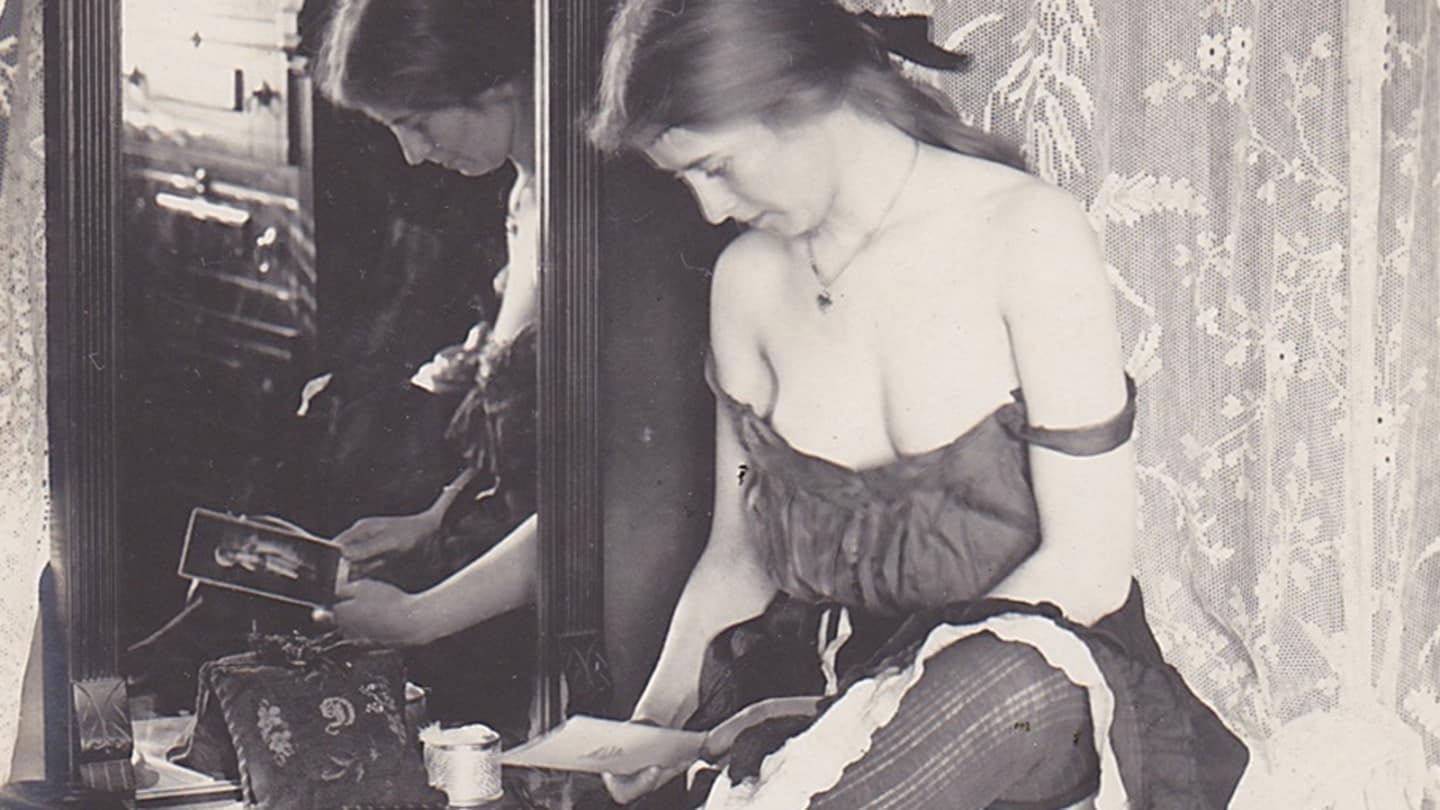

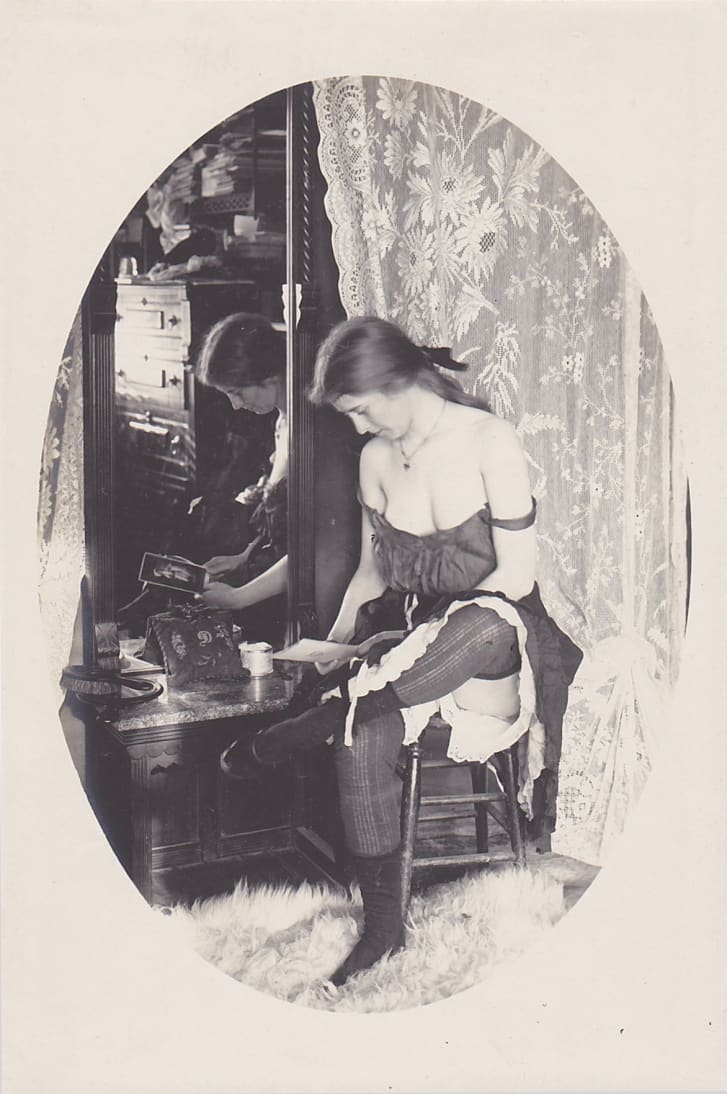

Given that photography was still an emerging technology, an emerging creative medium, when these “working girls” posed for William Goldman in the 1890s at a Reading, Pennsylvania brothel, the entire exercise transcends their initial business liaison. The instantaneous concept of click-and-shoot was still decades away. To be photographed required sitting very still. The women featured in Goldman’s collection obviously caught his eye. Not just anyone is asked to be the subject of artistic documentation.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

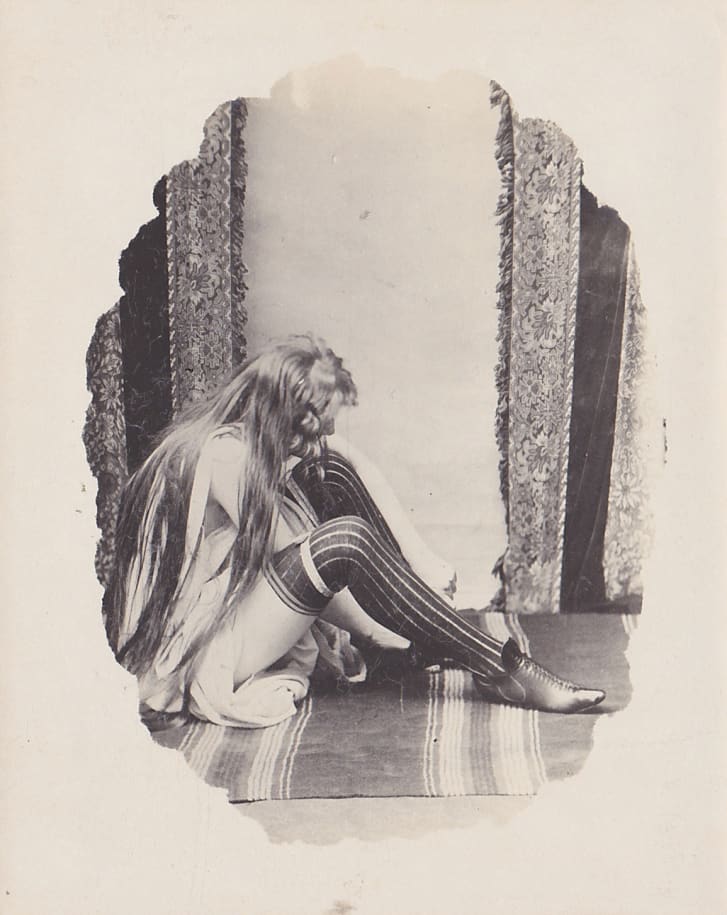

The local photographer and his anonymous muses appear to straddle an artful titillation, at times striving toward Degas nudes and at another, more in the spirit of a strip and tease. There is a beauty in even the most mundane moments.

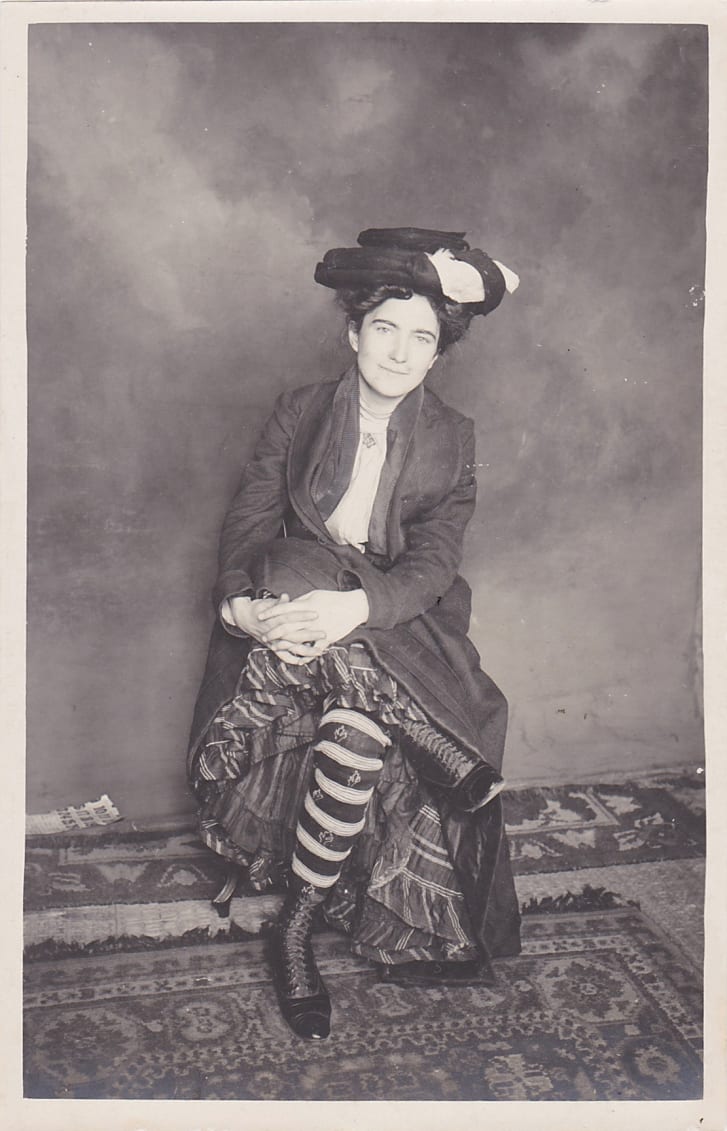

Among Goldman’s models, my own gaze zeroed in on the striped stockings and darker shades of their risqué brassieres. These ladies of Reading, Pennsylvania, might not have had the wealth of Madame du Barry, celebrated mistress of Louis XV of France, or the fame and freedom of a silver-screen sex goddess such as Mae West. But they sought to elevate their circumstances, to feel lovelier and more fashionable, with a daring pair of knickers.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

To feel special is fundamental to the human condition. Few opportunities outshine a sense of specialness than when an artist asks to record your looks, your beauty. Under the right circumstances, to be the object of admiration — of desire — to be what is essentially objectified is not only flattering. It can also provide a shot of confidence and a sense of strength and power and even liberation, however lasting or fleeting.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

For these working girls who were already going against the drudgery of toiling in a factory or as a domestic, who were surviving in a patriarchal world by their wits and sexuality, the opportunity to sit for Goldman was very likely not only thrilling. It was also empowering.

One can only imagine the mutual giddiness prevailing among them all, too, at the possible outcome from all these lost afternoon shoots. In a singular image from this collection appears Goldman striking a pose as proud as a peacock. It’s one of stock masculinity in the canons of classic portraiture (though usually in military uniform), and like his muses, presented in all his naked glory. By sharing in the objectivity of the process, Goldman basks in the specialness his models must have felt. By stepping around the lens, he becomes a true confidante.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

It suggests a balance of power between artist and muse, man and woman — at least behind closed doors. Their collective decision to strip and strut for the camera reveals a shared lack of shame for the body beautiful and, in that, a shared, albeit secret, defiance of cultural mores.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

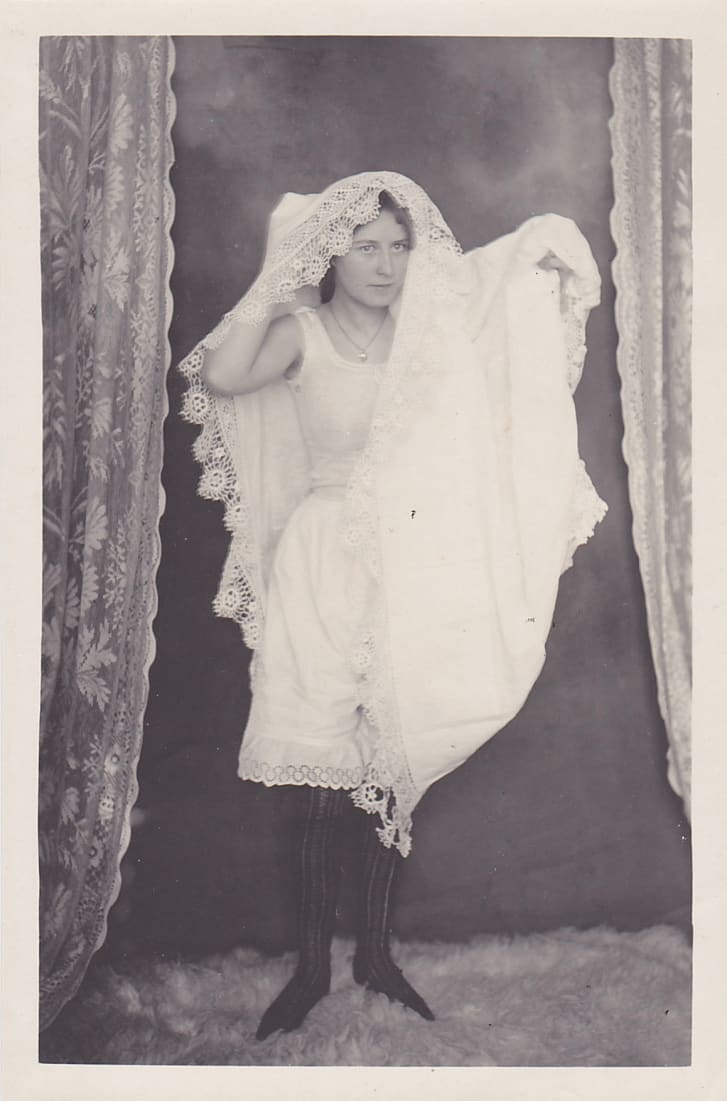

By all accounts from curator Robert Flynn Johnson’s devoted research on this once-lost collection, Goldman seems to have kept his treasured collection as a personal trove. As a successful photographer of weddings and social events, it was most certainly not in his interest for the public to know about his private creative pursuits.

Courtesy Serge Sorokko Gallery/Glitterati Editions

The brothel was a necessary evil in town, where men with certain desires visited women who would oblige. In this case, it was the desire of a man to capture the beauty and sensuality of the women he befriended. There is much to learn and (most of all!) take pleasure in with this discovery.

As these lost photographs illustrate more than a century later, one period’s “social problem” is another’s cultural revelation.