The New York Times / Hahna Yoon / October. 19, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/19/style/hanbok-k-pop-fashion.html?action=click&module=Features&pgtype=Homepage

When the K-pop band Blackpink released the music video for their song “How You Like That” in June, fans began asking about the group’s outfits, which appeared at once traditional and contemporary. Who was the designer behind Jennie’s cropped pink jacket, they wanted to know, and what inspired the look?

In the past few years, similar design concepts have been spotted on members of K-pop groups like BTS, SHINee and Exo. They are fresh takes on a centuries-old form of Korean dress called a hanbok. Scroll through the #hanbokstagram hashtag on Instagram and you’ll find thousands of posts with updated looks.

While a hanbok — which usually consists of a jeogori (jacket), paired with baji (pants) for men and a chima (skirt) for women — is generally reserved for holidays and special occasions, contemporary designers have been reimagining it.

Some modern hanbok brands have been boosted by K-pop stars who command devoted stan armies. Kim Danha, of the label Danha, said her brand’s site saw nearly 4,000 visitors a day after her jacket appeared on Jennie in the Blackpink video.

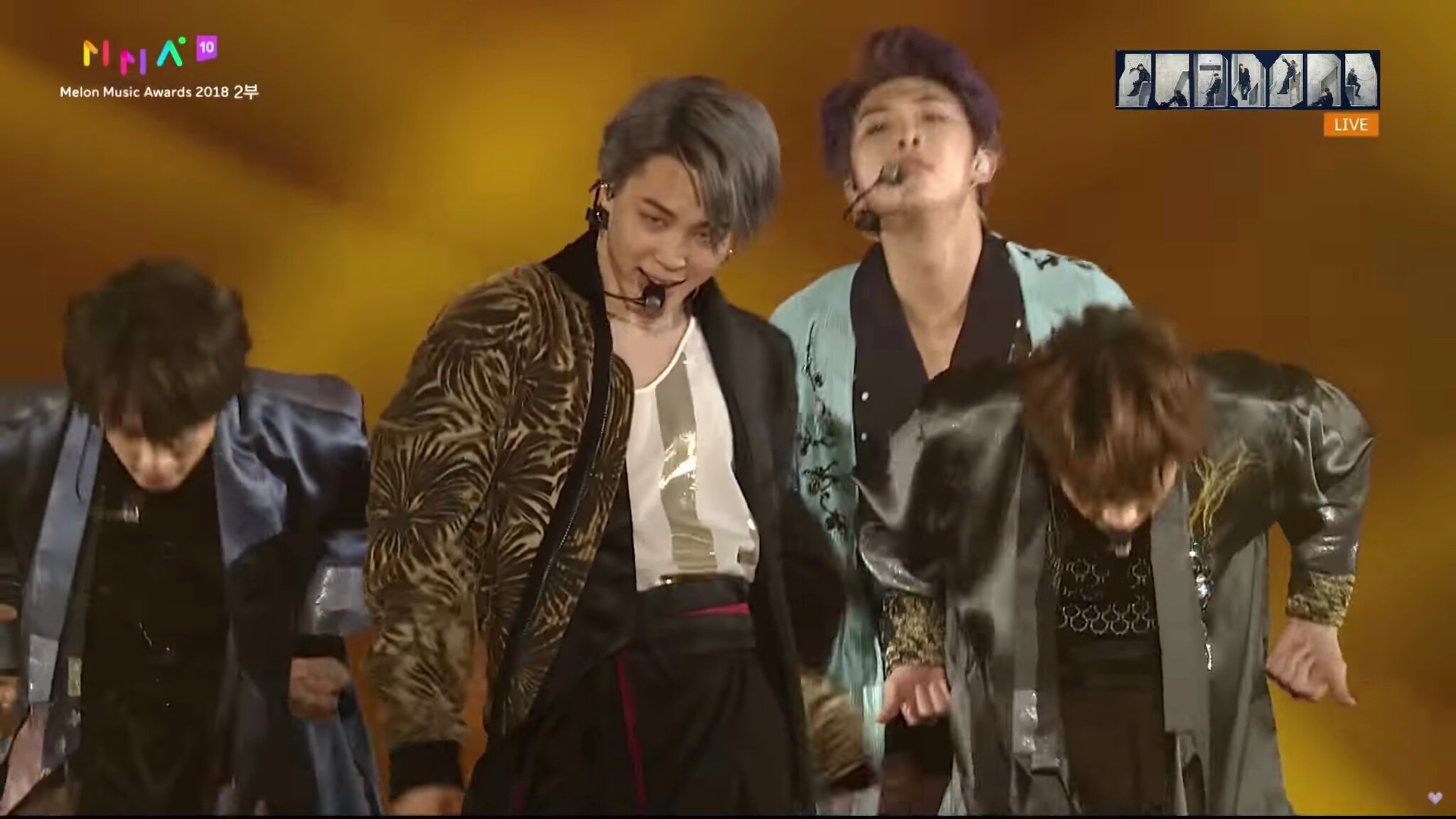

Leesle Hwang, the designer of the brand Leesle, saw an increase in sales after Jimin of BTS wore one of her hanbok ensembles at the 2018 Melon Music Awards in Seoul. “It’s incredible how many people got to know Leesle through that one appearance,” she said. Another brand, A Nothing, gained some 8,000 followers after Jungkook, another BTS member, wore its clothes.

“The reason why people became interested in hanboks, especially outside Korea, is this growth soft power as demonstrated by K-pop,” said Kan Ho-sup, a professor of textile art and fashion design at Hongik University.

In Korea, the style can be traced back to the first century B.C., and was traditionally made out of silk dyed in vivid colors. (Before the advent of Western clothing in Korea, all clothing was simply a hanbok; the word itself means “Korean clothing.”)

According to Minjee Kim, a dress historian in San Francisco, Western clothing completely replaced the hanbok in the early 1980s. Almost concurrently, there were designers incorporating traditional Korean elements into Western designs.

Ms. Kim attributed the late designer Lee Young-hee as the first designer to transcend the boundaries of hanbok design. At Paris Fashion Week in 1993, the designer sent bare-shouldered models down the runway wearing hanboks without a jeogori.

Around the same time, the stylist Suh Younghee became interested in hanbok because she felt it could counter the industry’s obsession with Western labels. She began playing with hanbok conventions at Vogue Korea, where she worked. In the February 2006 issue, she styled jokduri (traditional coronets) on models with vibrantly dyed hair, an image that defied any conventionality the garment might convey. In 2014, she helped start the Hanbok Advancement Center, which leads programs on hanbok education and funds related events.

In the early 2000s, the designer Kim Young-Jin started rethinking the style’s tradition while studying with Park Sun-young, a master of hanbok needlework. Ms. Kim learned about a type of traditional military uniform worn by men during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1897) called the Cheolik, and recreated it as a midi-length wrap dress with a V-shaped collar, tailored to fit the female form. “Just because something is inspired by the past doesn’t mean there’s no creativity in it,” she said.

When images of the garment began circulating, other labels started creating similar looks. Ms. Suh, who often collaborates with Ms. Kim for high-end fashion photo shoots, called the number of “copies” troubling. “I’m not saying this because we’re close, but Tchai Kim’s Cheolik one-piece marked a new era of hanbok design,” Ms. Suh said.

After experimenting with leftover textiles at her parents’ bedding and curtains shop, Ms. Hwang, of Leesle, began selling her pieces online and eventually started Sonjjang, a hanbok line focusing on what she called “altered hanboks,” with lace and frills, and shortened sleeves and skirt lines.

When Ms. Hwang began thinking about creating hanboks for everyday wear, she turned to the internet. A majority of traditional hanbok shops were, and still are, reluctant to stray from the expensive, ’70s-style tailored-to-fit designs, but online communities devoted to hanbok subcultures were already discussing what changes they wanted in the garment as early as the mid 2000s.

Taking their feedback into account, Ms. Hwang founded Leesle in 2014, selling easy-to-wash hanboks. Her clothes are available in extra small to large, unlike many companies that offer only one size. “I don’t want to be exclusive,” Ms. Hwang said. “Bigger people. Older people. Slender people.” Her garments are also more modestly priced than their silk forebears, at under $200 apiece.

“It’s still uncommon to see people in modern hanbok,” Ms. Hwang said. “And while it doesn’t need to be worn all the time, it can become a basic item like a white T-shirt or black pants.”

Kim Danha said she hopes those who encounter her brand come to appreciate Danha’s environmental ethos. The label has a focus on sustainability; 30 to 50 percent of its fabrics are recycled polyester or organic cotton.

“Sustainability and traditional Korean design go well together because compared to Western shapes, original hanbok designs produce less scraps,” she said. The hanbok’s straight lines, she said, waste less fabric than, for instance, the rounded collar of a T-shirt.

She cited the worsening air pollution in South Korea as a motivation for her interest in environmental issues.

However, so-called slow fashion is a tough business, she said. Upcycling discarded wedding dresses is labor-intensive, and everything, even printing on fabric, costs more when you take the eco-friendly route, she said. So while she tries to uphold that model, most important to her is honoring the hanbok and giving it a place in the future.