There’s a tendency, when looking back on the history of women’s suffrage in the United States, to assume that it was inevitable that women would get the right to vote: By the time Tennessee became the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment, on August 18, 1920, 15 states had already granted women suffrage, starting with Wyoming, which became a state in 1890. (As a territory, it gave women suffrage in 1869.) How long could such an electoral-rights imbalance reasonably be expected to survive?

Then again, was it really inevitable? The amendment’s passage was the culmination of probably the longest sustained sociopolitical movement in American history, and even so it came down to a single 24-year-old Tennessee state legislator’s vote—changed from nay to aye after his mother wrote him a letter lobbying him to do so—or it wouldn’t have happened, at least not in 1920. And even then, the 19th Amendment hardly put an end to systematic disenfranchisement (and not only of women) in this country. On a practical basis, Black women in the South, and to some extent Black women anywhere, still didn’t get to exercise their right to vote (as Black men hadn’t and didn’t)—not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 swept away many of the tactics vote suppressors had used for decades to thwart them. Native American women (along with Native American men) didn’t get the vote until 1924, when their citizenship was recognized (they weren’t guaranteed the right to vote in every state until 1962); all Asian-American citizens didn’t get the vote until 1952, when the McCarran-Walter Act granted all people of Asian ancestry the right to become citizens. As an additional point of comparison, women in Switzerland were not granted the right to cast a ballot in their national elections until 1971. Imagine how different this country might be—socially, culturally, politically—if women had been forced to wait 51 more years before successfully seizing the right to exercise their power at the polls. Imagine how different things might be if women never got that right.

The contemplation of hypothetical, alternative histories—the conjuring of counterfactual scenarios and the spinning of stories about what the world and our lives might be like if this, this, or this had happened or not—is an endlessly fascinating pastime. (The “What if the Nazis had won?” alternative-history subgenre has lately seen a particularly strong resurgence with the bingeworthy Hollywood adaptations of The Man in the High Castle and The Plot Against America.) It’s also a deeply fraught exercise, with each counterfactual pivot triggering an endless range of possible implications and outcomes, each of which in turn sets in motion its own innumerable ripples of “what if.” We can’t say definitively how a century of women voting has shaped the world we live in or what that world would look like in its absence. But we can crunch some numbers and offer some data-driven possibilities. We can, for instance, examine state-by-state exit polling from presidential elections to see whether and how the Electoral College might have swung if men alone had wielded the ballot.

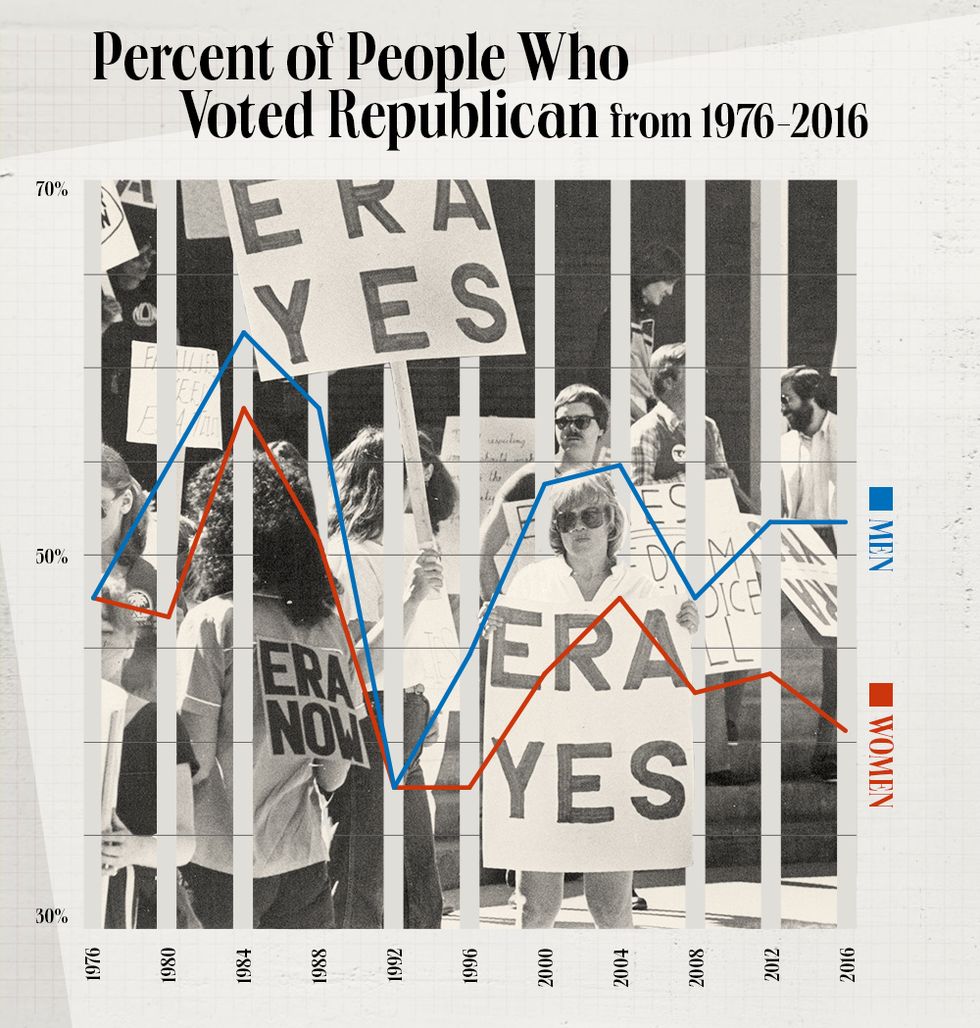

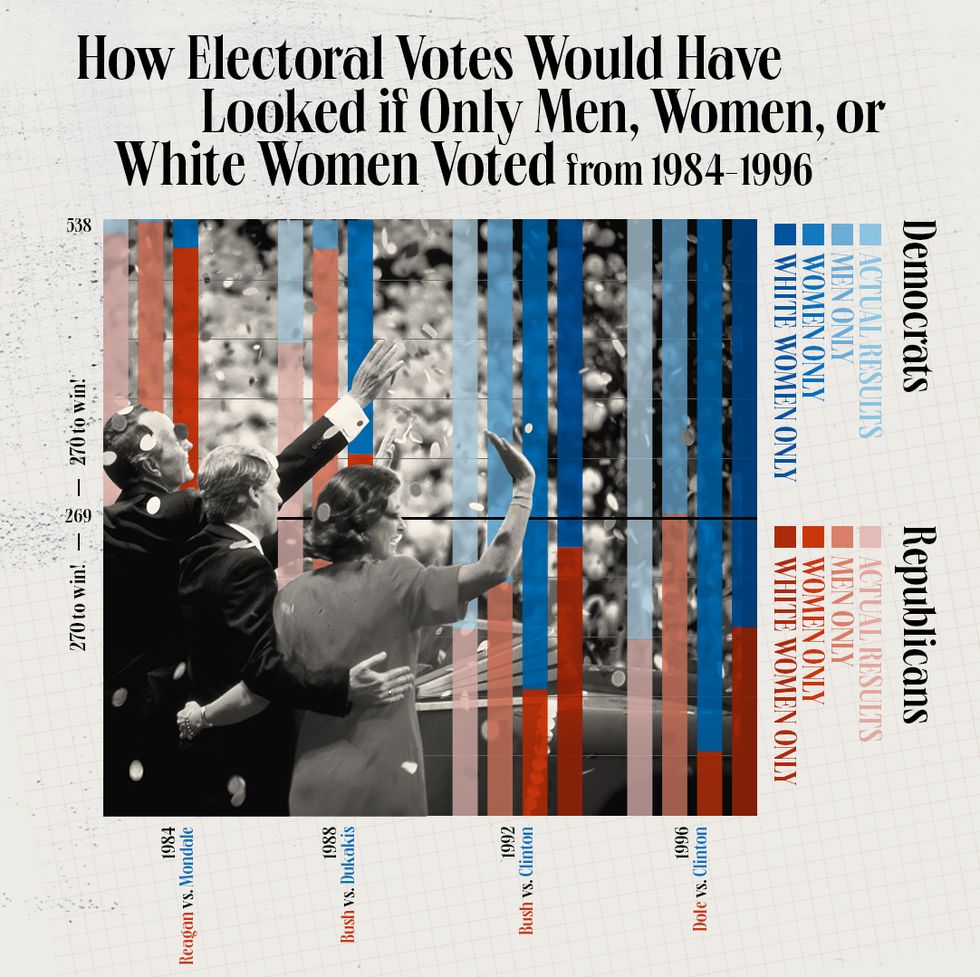

And when we do so, here is what we find: Women’s and men’s votes have been diverging in significant ways for several decades, so much so that at least two relatively recent elections might very well have gone the other way—from the Democratic candidate to the Republican—if women had still been barred from the polls on election day.

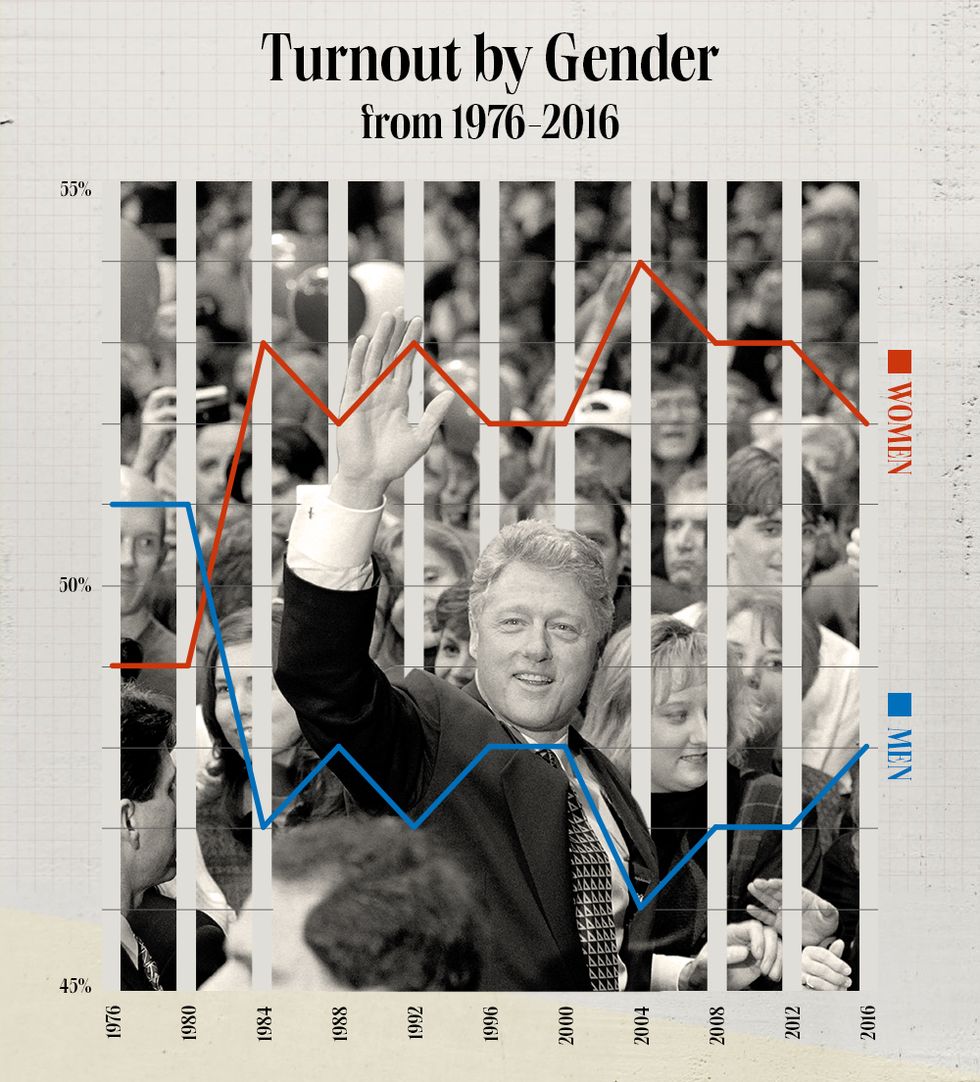

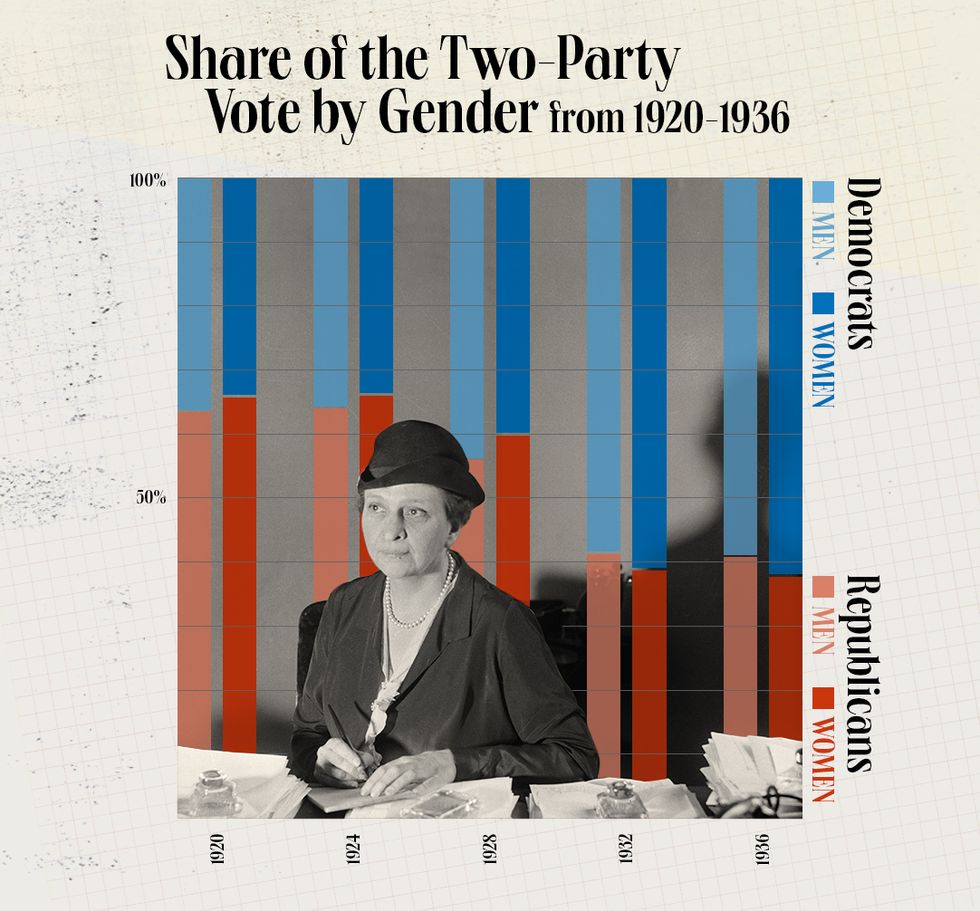

For a while after the 19th Amendment went into effect, it looked as if the entry of women into the electorate would have little or no tangible impact at all. Women didn’t vote at nearly the level men did—36 percent of eligible women cast a ballot in 1920, versus 68 percent of men—and when they did vote, they tended to do so pretty much as men did. “Suffragists get a bad rap because the amendment passes, and then the world doesn’t change,” says Susan Ware, author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. “It wasn’t as if all of a sudden women threw all the politicians out of office and decided to end war and end prostitution and all these things. But suffragists never claimed that the world would change. They didn’t say women would vote as a bloc and war would end.”

In some ways, the specter of a woman’s vote seems almost to have had more power than the vote itself—at first. “Right after 1920, we get the Sheppard-Towner Act, which provides support for mothers and infant care,” says Christina Wolbrecht, director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the University of Notre Dame and co-author of A Century of Votes for Women: American Elections Since Suffrage (which is where the 1920 voter-turnout stats above come from). “We also get the Cable Act, which says that if you’re a woman and you marry a foreigner, you don’t immediately lose your American citizenship. And then it turned out that women didn’t vote that differently than men and most of them stayed home, so politicians decided that they weren’t really a threat anymore, and so we don’t really need to pay as much attention to their agenda items. So you don’t see as much of those issues in the ’30s and into the ’40s.”

But what you do see in the ’30s and ’40s is women deploying a political savvy honed during the long campaign for suffrage, gathering and exercising a type of soft power to mold policy and shape national agendas from positions just out of the spotlight. “When we think about the impact of women’s suffrage,” Wolbrecht says, “an obvious focus is outcomes of elections. But we also might ask about something we would call in political science the second face of power. One face of power is, something is being debated and you can determine the winner or the loser. The second face of power is just getting that thing to be talked about in public life, to be on the political agenda. And by becoming voters, women had more power to influence the political agenda.”

Ware offers the Social Security Act as an example of this sort of exercise of soft power. “The secretary of labor at the time that was passed was Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in the cabinet,” she says. “And Frances Perkins was a former suffragist.” (In fact, so pervasive was Perkins’s influence on the blossoming of social programs during the FDR administration that Collier’s magazine would later describe those accomplishments as “not so much the Roosevelt New Deal as…the Perkins New Deal.”)

But for the most part, if your hopes as a suffragist, or your aims as a counterfactualist, are to find in the early decades of women’s voting evidence that the ballot was a power wielded by women to bring about sociopolitical change, you are doomed to disappointment. “In eras where there’s a lot of traditional ‘family values’ conservatism, where men are the primary breadwinners, stay-at-home women will support the conservative party very strongly,” says Kevin Corder, a professor of political science at Western Michigan University and co-author with Wolbrecht of A Century of Votes for Women. “In countries where they introduced suffrage at a time when you had a lot of traditional values, women were overwhelmingly voting for the conservative party. And that’s what the U.S. electorate in the ’50s did.”

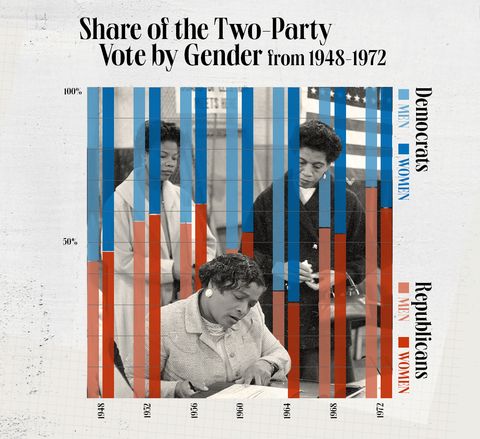

In fact, to the extent that there was a partisan gender gap—a measurable difference between women’s and men’s relative support for the same candidate—throughout the 1950s and into the early ’60s, it showed a tendency for a slightly higher proportion of women than men to vote Republican. That changed by 1964, with both women and men favoring Lyndon Johnson in his trouncing of Barry Goldwater and women favoring the Democrat to a slightly greater degree, a pivot that heralded what became a slowly growing schism between the sexes, driven by some combination of men migrating rightward and women leftward.

“The 1960s is also when the parties become sharply defined on social welfare,” Wolbrecht says. “One party says government is the problem; the other says government is the solution. If you’re economically vulnerable, the party that wants to have a social safety net may be more attractive to you. But even for women who are not economically vulnerable, something like 60 to 70 percent of the growth in middle-class women’s employment comes from the public sector. They are the public schoolteachers for the baby-boom kids. They’re the nurses in public hospitals. They are the social workers in all of these Great Society programs. They’re all these sorts of things that make their own economic interests much more linked to an active federal government.”

There is an insistent article of faith among scholars of women’s suffrage that goes like this: “Women” is not a voting bloc. “The category of ‘women,’ when it comes to voting, is just too broad,” Ware says. “I’ll give you two examples. One is the suffrage movement itself, where you had women who were for the vote and a lot who were against it. And the Equal Rights Amendment, where you had a lot of feminists struggling for the ERA and then you had antifeminists who were vehemently opposed to it. You have to be very, very careful about talking about women as a group and any expectation that there would be a women’s bloc; it just doesn’t hold up.” And with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 opening the electorate up to far greater numbers of Black women, it would soon become clear just how absurd it is to think that women all vote the same.

Ronald Reagan’s 489–49 electoral-vote shellacking of Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election was fueled, not surprisingly, by support from both men and women. What was surprising, or at least notable, was the difference in the scope of support for Reagan between the sexes. Reagan outpolled Carter among men by a whopping 55–38 margin (Independent candidate John Anderson took 7 percent of the votes); among women, Reagan barely squeaked out a 47–46 victory. Feminists seized on the eight-point (55 versus 47 percent) “gender gap” in votes for Reagan (Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women at the time, is generally credited with coining the term) as a way to highlight the importance of the women’s vote and of promoting policies that women care about. (This came at a time when the parties were becoming distinctly polarized around some of those issues; Republicans removed support for the Equal Rights Amendment from their party platform in 1980 for the first time in 40 years.)

The gender gap waxed and waned, though mostly waned, until 1996, when Bill Clinton ran for his second term, against Bob Dole, and the gap ballooned to 11 percent. The interesting thing about this particular shift is what it reveals about the dynamics that underpin it. In the previous election, the gap had been only 4 points, with both women and men favoring Clinton over George H.W. Bush—women giving Clinton 45 percent of their vote and men 41. (The numbers are skewed by the fact that H. Ross Perot performed so well as a third-party candidate, taking 21 percent of men’s votes and 17 percent of women’s.) “What happens in 1996,” Wolbrecht says, “is that women become more Democratic, but it’s also that many men returned to the Republican Party.” This is an important point: The gender gap is not just about how women vote. As Wolbrecht puts it, “1996 is such a great example of how the gender gap can be driven by both men and women.”

And those antipodal shifts by men, in turn, lead us to the first of our “What if women never got the right to vote?” electoral overturns: A close examination of state-by-state exit-poll numbers indicates that if women hadn’t voted in 1996, Bob Dole would have flipped the results in nine states and won a narrow victory, depriving Clinton of a second term. Here are a few other things that an all-male electorate would have deprived Clinton of: credit for four straight years of budget surpluses and the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in U.S. history; a successfully negotiated end to the war in Kosovo; and making Madeline Albright the first female secretary of state. Dole would have enjoyed Republican control of both houses of Congress, giving him the opportunity, perhaps, to achieve more in his first term than Clinton was able to in his second, so maybe he would have managed to abolish the four cabinet departments (Housing and Urban Development, Energy, Commerce, and Education) he had in his sights or to sign a bill (like the one Clinton vetoed toward the end of his first term) to allow drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. One distraction he (and the country) likely would not have faced: the impeachment of a sitting president. Monica Lewinsky would probably not have become the household name she did. And who knows what impact all that might have had on Hillary Clinton’s political career.

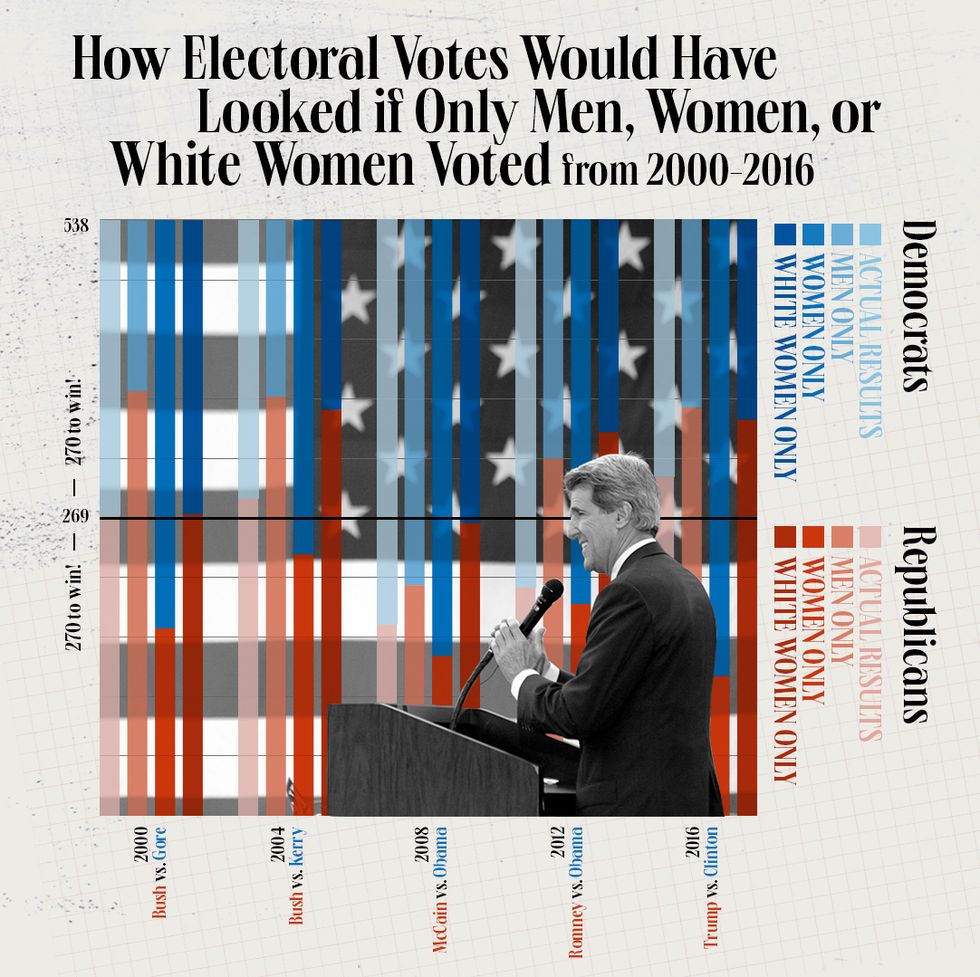

Of course, if that’s the way history had actually gone, all bets would be off for how subsequent elections would have unfolded—since two Dole terms means no George W. Bush hanging-chad victory in 2000, and on and on. So let’s file Dole’s 1996 triumph away in the annals of alternative history and travel ahead another 16 years to take a look at the second upset the all-male electorate would have bestowed. This one, again, is the denial of a second term to a Democratic president, with Mitt Romney snatching nine additional states away from Barack Obama in 2012 and scoring a 322–216 Electoral College win. Here are a few things that happened in Obama’s second term that might thus have vanished into the alternative-history mists: the Iran Nuclear Deal, the Clean Power Plan, the Paris climate accord. One other thing that almost certainly would have gone away if Romney had run in 2016 for his second term: the presidency of Donald Trump. (Didn’t we warn you this was a fraught exercise?)

To illuminate the influence of women’s votes on presidential elections from a different angle, we also crunched the numbers on the opposite postulate: What if only women had the right to vote? A few highlights: Bill Clinton beats George H.W. Bush by a lot more in 1992 and absolutely demolishes Bob Dole in ’96; Al Gore wins with a comfortable 368 electoral votes (and no need for a Supreme Court intercession) in 2000; John Kerry claims a victory in 2004; Obama cruises to two terms; and Hillary Clinton actually does become the first woman president in U.S. history, beating Donald Trump 412–126 and presumably presiding this year over many joyous celebrations of the centennial of women’s suffrage.

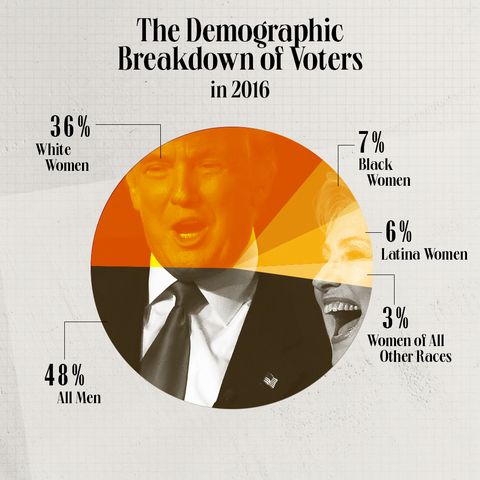

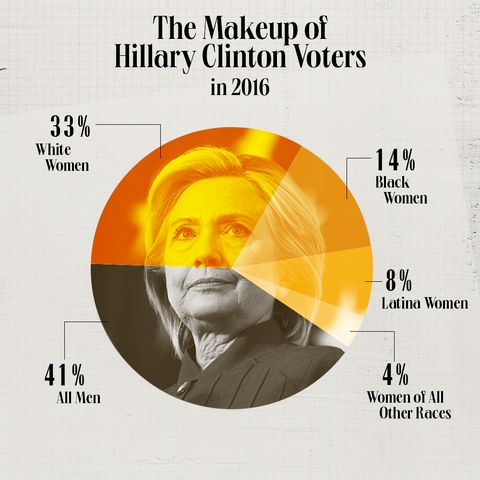

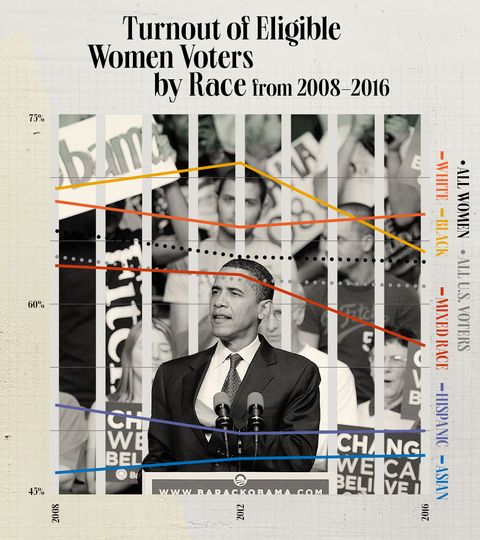

If that litany of outcomes reinforces your belief that women have become a staunchly reliable source of Democratic votes…then you haven’t been paying close enough attention. Remember “‘Women’ is not a voting bloc”? Because a deeper crunch of the exit-poll data reveals just how consequential the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act truly was on the electoral calculus: It’s not “women” who, if they were the only ones with the vote, would have been responsible for sweeping an unbroken string of Democratic candidates into office over the past three decades; it’s Black women and, to a slightly lesser extent, other women of color. If the power to vote had been held by white women only, every presidential election over those 32 years would have had the same outcome, with one exception: Romney would have beaten Obama in 2012 (and by a bigger margin than if only men had voted in that election).

Trump would have won in 2016 by 51 more electoral votes than he did. It’s only the overwhelmingly Democratic votes of non-white women that push the overall category of “women voters” resolutely into the Democratic column. As University of Michigan political scientist Ken Kollman pithily sums up: “Trump won the majority of white women. He got slaughtered among Black women and Latina women.”

Above: In 2016, nonwhite women made up 16 percent of all voters yet contributed to 26 percent of Clinton’s total votes. If just white women had voted, Trump would have won by an additional 51 electoral votes.

Kollman is far from alone among electoral scholars in anticipating the possibility that the 2020 election might emerge as a gender-gap pivot point—and a harbinger of challenging times to come for the Republican Party. “The data show that Trump is uniquely disliked by women,” he says. “And a lot of that is driven by women under 45. The partisan gap between men and women is increasing in the population as a whole, but it’s really a big step by generation. You go down in age and the gap gets bigger and bigger and bigger. And the modern Republican Party is in trouble. It’s not just that young people are being driven away from the Republican Party, which is true, but that young women are being dramatically driven away from the Republican Party.”

Heading into this centennial year for women’s suffrage, Susan Ware would find herself trying to conjure in her imagination a society where women can’t vote. “I went to my first feminist demonstration in 1970, on the 50th anniversary of women voting,” she says. “That’s not that long ago! I was born in 1950, and women had been voting for only 30 years, and that seems really bizarre to me. I haven’t found a really good way of conveying this to people, but just try to imagine a landscape where half the population is arbitrarily denied the right to vote because of their sex. To me, that’s the importance of suffrage: that we got past that hurdle.”

Ware, who has spent much of her career writing about the early suffragists, also likes to torture herself by trying to imagine what her biographical subjects would make of how far—or not—the country has come since 1920: “If I could bring my women up to the present and say, ‘All right, here’s where we are 100 years later,’ what would they think? Would they say, ‘Way to go, this is much further than we expected!’ or would they say, ‘Come on, Susan, not enough has happened.’ I go back and forth.”

One thing she does know, though, is that the right to vote, and to have a voice, is not something to be won and then taken for granted. “The suffragists needed to get women the vote, and it was a hard and a long struggle, and then it’s been up to women in the years since to figure out what they want to do with it,” Ware says. “And that process is still ongoing. And it will be going on long after I’m not here. But I see myself as being part of something bigger. And I see the centennial as being part of something bigger. I would hope that maybe you will get your readers thinking about that. And then the last line of your story has to be to remind them to vote no matter what.”