From Vogue/By LIANA SATENSTEIN

November 2, 2020

Today we have celebrities on social media imploring their followers to go vote, but in 1990, there was “Rock the Vote,” which featured the music industry’s range of pop stars and celebrities to speak about the importance of voting. The initiative was created 30 years ago by Virgin Records music executive Jeff Ayeroff in a response to censorship of rock and rap lyrics, and who had seen it as suppression to freedom of speech. The initiative’s purpose was to share information and encourage voter participation among the youth. While the campaign kicked off in 1990, the organization still exists today. But the ’90s videos are particularly special, in all of their grainy and experimental glory, featuring the likes of Lenny Kravitz, Madonna, and Iggy Pop. And while each message was tailored to the participants personality, the message was the same: Get out and vote.

The videos are still available on YouTube, some of which are compiled by fans, and others by Rock the Vote itself. In one clip, we see Iggy Pop wearing his most signature look, which is him shirtless and a low-slung pair of jeans, rotating on a disc while simultaneously being mummified in tape. (It looks painful!) Another standout video features Lenny Kravitz with a patchwork jacket, his go-to look during the era. “Tell them what’s on your mind,” he says in the video. Sarah Jessica Parker fans will be overjoyed to see her with then-boyfriend Robert Downey Jr. in an ad by director Lawrence Bridges. The baby-faced duo wears all black and performs together in an art house style film that taps into the concept of “Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil.” SJP leaves us with the words: “It is your turn to speak. Your vote, is your voice.”

The most jaw-dropping outfit was Madonna’s. At the time, the Queen of Pop boasted a Marilyn Monroe-style coif, and was snapping and singing with her backup dancers, all while wrapped in the American flag. (Underneath it, she wears red lingerie.) She sang the song “Vogue” but replaced the word with “Vote.” The off-the-cuff tune had the following lyrics: “Abe Lincoln, Jefferson Tom/They didn’t need the atomic bomb/We need beauty, we need art/We need government with a heart/Don’t give up your freedom of speech/Power to the people is in our reach.” (She also rapped: “If you don’t vote, you’re gonna get a spanking.”) The look was controversial and it drew criticism from Veterans of Foreign Wars for how Madonna draped herself in the flag. In response, her publicist noted: “It is essential that people should vote. She’s trying to get that message across in a humorous, dramatic way. But she’s very serious about the issue.”

As much controversy as the campaign may have caused, it was successful in getting young people to vote. At the time, according to a New York Times article from October 20, 1990, 10,000 college students from five California campuses registered to vote in the wake of the campaign. Since then, other campaigns have followed suit, like MTV’s “Choose or Lose”, which aired a clip of Madonna and Iggy Pop in 1996. The duo wore red and blue eyeshadow, and had “Choose or Lose” animated into their eyes. (Moss wore a dress dotted with “Choose or Lose” pins, including on cups that acted like pasties. Iggy Pop went shirtless with pin-dotted pants, and Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers made a cameo at the end in a pin-covered floppy hat.) Back in 2004, P. Diddy launched the “Citizen Change,” and released those iconic “Vote or Die” T-shirts, which were recently revamped by Pyer Moss.

The “Rock the Vote” visuals were groundbreaking and had that stellar free-for-all flair seen in other MTV-backed productions, like Sofia Coppola and Zoe Cassavetes’s Hi Octane.The aesthetic of the ’90s “Rock the Vote” campaigns are still making an artistic impact, too. Most recently, New York-based downtown director Dani Aphrodite, along with the organization Soft Power Vote, released the “Level Up” series, a nostalgic collection of videos that feature downtown New York’s favorite faces with messages to vote, all of which were heavily influenced by “Rock the Vote.” Turns out that while times have changed, the message and influence of “Rock the Vote” still stands and feels just as strong as it did since its inception 30 years ago.

From BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES / BBC

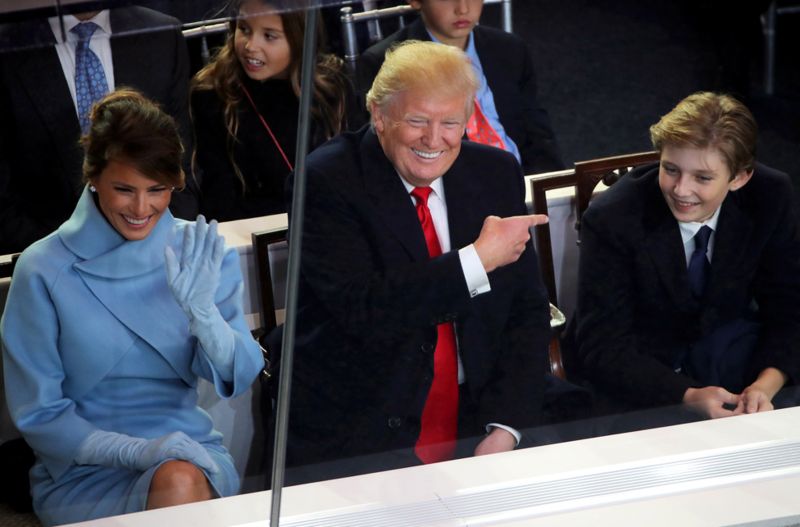

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES / BBCPresident Donald Trump, 74, and Democratic challenger Joe Biden, 77, each have more than seven decades of personal and professional experience behind them.

Here is a selection of photos that span their lives.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTALAMY

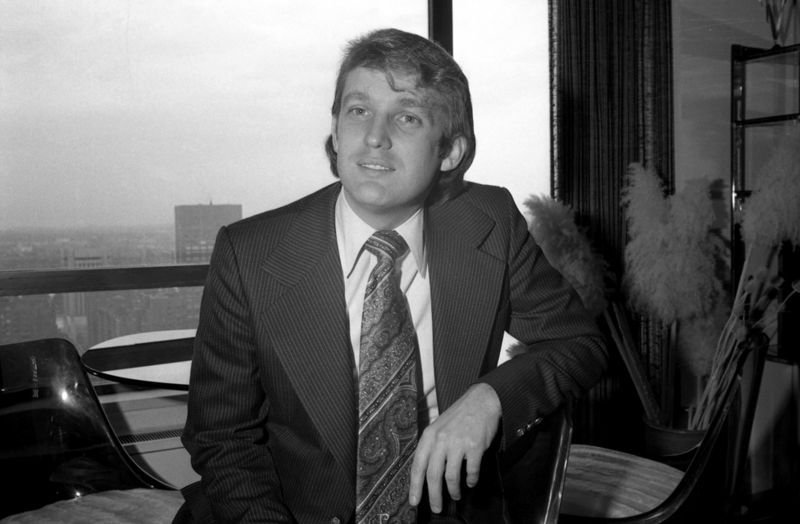

IMAGE COPYRIGHTALAMYBorn in the wake of World War Two, in June 1946, Donald John Trump was the fourth child of New York real estate tycoon Fred Trump and Mary Anne MacLeod Trump. Despite the family’s wealth, he was expected to do the most menial jobs within his father’s company and was sent to a military academy at age 13 after he started misbehaving in school.

He attended the University of Pennsylvania and became the favourite to succeed his father in the family business after his older brother, Fred, opted to become a pilot.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTALAMY

IMAGE COPYRIGHTALAMYJoseph Robinette Biden Jr was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1942. He was the first of four children, in an Irish-American Catholic family. Young Joe’s biggest challenge was overcoming a speech impediment – a stutter – that afflicted him well into high school. His technique of practising speaking in front of a mirror paid off after several months.

Mr Biden attended the University of Delaware and then law school at Syracuse University.

He later married his first wife, Neilia, and started his political career in Wilmington.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESMr Trump says he got into the property business with a “small” $1m loan from his father, before joining Fred Trump’s company. There, he helped manage an extensive portfolio of residential housing estates in New York City, eventually taking control of the company. In 1971, he renamed it the Trump Organization.

Six years later, Donald Trump married his first wife, Ivana Zelnickova, a Czech athlete and model. His children from his first marriage – Donald Jr, Ivanka and Eric – now help run Trump Organization, though he is still chief executive.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

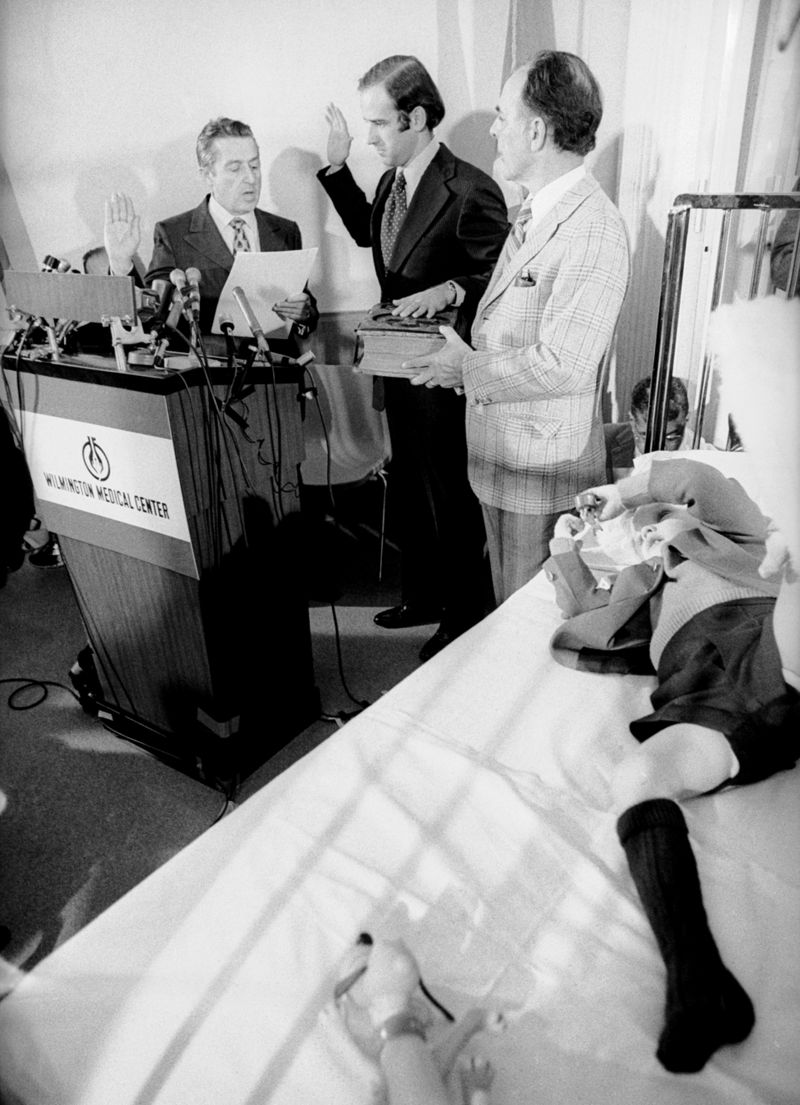

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESJoe Biden was eagerly waiting to take up his seat in the US Senate, having been elected in 1972, when tragedy struck. His wife and infant daughter Naomi were killed in a car accident. His sons Beau and Hunter were seriously injured.

Mr Biden famously took the oath of office for his first term as a Democratic Party senator from the hospital room of his toddler sons.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTJOE MCNALLY / GETTY IMAGES

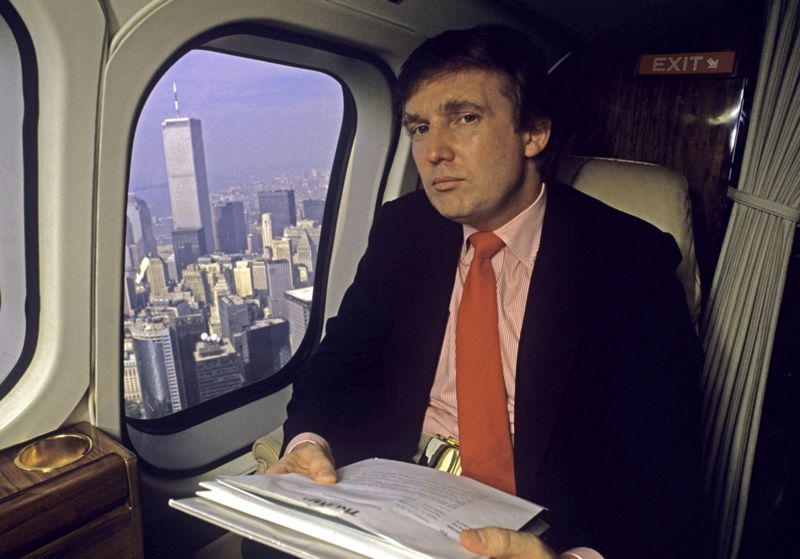

IMAGE COPYRIGHTJOE MCNALLY / GETTY IMAGESIn the late 1970s Mr Trump stepped his ambitions up a gear, shifting his property focus from Brooklyn and Queens to glitzy Manhattan. After snapping up a rundown hotel and transforming it into the Grand Hyatt he built the most famous Trump property – the 68-storey Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue. It opened in 1983.

Other properties bearing the famous name followed – Trump Place, Trump World Tower, Trump International Hotel and Tower – and his powerful brand began to draw media interest.

But not everything he touched turned to gold. Mr Trump’s ventures have led to four business bankruptcy filings.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTARNIE SACHS / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTARNIE SACHS / GETTY IMAGESDuring his first 14 years in Washington, Mr Biden rebuilt his personal life after the deaths of his wife and daughter. He committed to giving his sons a semblance of a normal life, and commuted each day from the family home in Delaware to Washington DC. He eventually remarried, to schoolteacher Jill Jacobs, with whom he had another child, Ashley.

Mr Biden established himself on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and began to build a national profile. In 1987, he launched his first go at the US presidency, but withdrew after he was accused of plagiarising a speech by the then leader of the British Labour Party, Neil Kinnock.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESProperty alone was not enough for Mr Trump, who moved into the entertainment sector, snapping up a clutch of beauty pageants in 1996: Miss Universe, Miss USA, and Miss Teen USA. In his personal life, after splitting with Ivana he married actress Marla Maples in 1993.

They had a daughter, Tiffany, before divorcing in 1999 – the same year Mr Trump’s father died.

“My father was my inspiration,” Mr Trump said at the time.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTWALLY MCNAMEE/ GETTY IMAGES

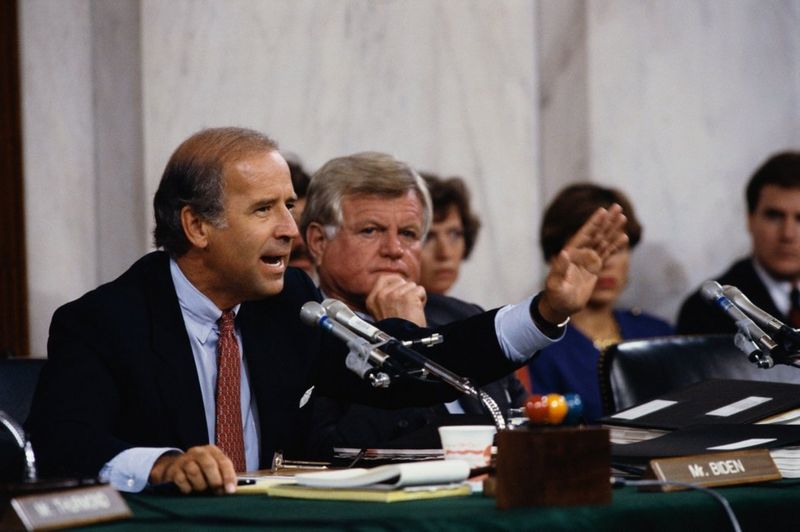

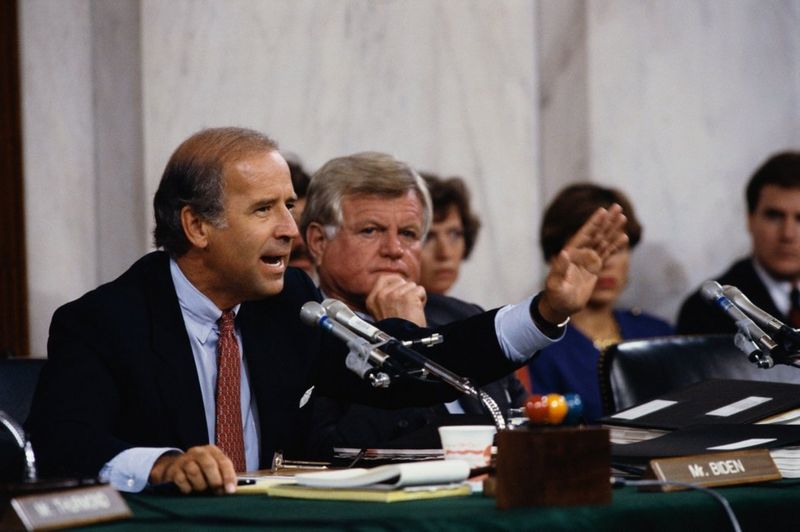

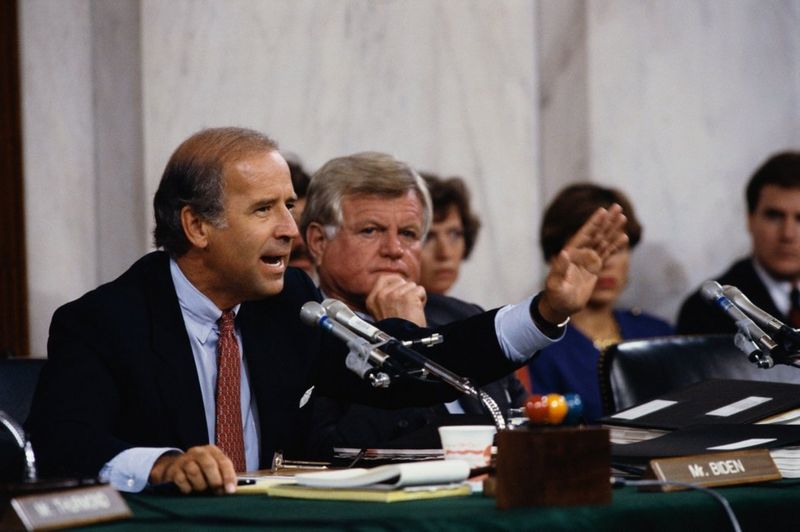

IMAGE COPYRIGHTWALLY MCNAMEE/ GETTY IMAGESOn 11 October 1991, the US public were glued to their TVs as Anita Hill, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee. The committee was holding a hearing into the nomination for the US Supreme Court of Clarence Thomas. Ms Hill alleged he had sexually harassed her on many occasions when they had both worked for the Reagan administration.

As chairman of the committee, Joe Biden led the hearing. His handling of Ms Hill’s evidence has long been criticised.

The hearing was conducted by an all-white, all-male panel, and several women apparently willing to back up Ms Hill’s account were not called by Mr Biden to testify.

Speaking in a TV interview in April 2019, Mr Biden said that he was “sorry for the way she got treated”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTRON GALELLA / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTRON GALELLA / GETTY IMAGESIn 2003, Mr Trump fronted a new reality TV show that played to his reputations as both a businessman and a media personality. Called The Apprentice. the programme featured contestants competing for a shot at a management job in Mr Trump’s commercial empire.

He hosted the show for 14 seasons, and claimed in a financial disclosure form that he had been paid a total of $213m by the network during the show’s run.

Meanwhile, in 2005, he married his current wife, Melania Knauss, a Yugoslavian-born model. The couple have one son, Barron William Trump.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTJOE RAEDLE / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTJOE RAEDLE / GETTY IMAGESMr Biden had another shot at the presidency in 2008 before dropping out. But while his campaign had failed to break through, he was to reappear later that year in a role that assured him international prominence. On 23 August 2008, Mr Obama introduced Joe Biden as his vice-presidential running mate.

It was a winning ticket and the pair eventually served two terms, establishing a close working relationship in which Mr Biden frequently called Mr Obama his “brother”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTCARLOS BARRIA / REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHTCARLOS BARRIA / REUTERSIt was not until June 2015 that Mr Trump formally announced his entrance into the race for the White House. His campaign for the presidency was rocked by controversies, including the emergence of a recording from 2005 of him making lewd remarks about women, and claims, including from members of his own party, that he was not fit for office.

But he consistently told his army of supporters that he would defy the opinion polls, which mostly had him trailing his Democratic rival Hillary Clinton. He said his presidency would strike a blow against the political establishment and “drain the swamp” in Washington.

He took inspiration from the successful campaign to get Britain out of the European Union, saying he would pull off “Brexit times 10”. Despite almost all the predictions, Mr Trump was victorious in the 2016 election. He was inaugurated as the 45th US president on 20 January 2017.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTMICHAEL REYNOLDS / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTMICHAEL REYNOLDS / GETTY IMAGESIn a surprise ceremony in the final days of his presidency, Mr Obama awarded Mr Biden the Presidential Medal of Freedom – the nation’s highest civilian honour.

“To know Joe Biden is to know love without pretence, services without self-regard and to live life fully,” the then president said.

It had been a successful partnership, but a period not without trauma for Mr Biden, whose son Beau died of brain cancer in 2015 at the age of 46. The younger Biden was seen as a rising star of US politics and had intended to run for Delaware state governor in 2016.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTWIN MCNAMEE / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTWIN MCNAMEE / GETTY IMAGESMr Trump’s re-election campaign has been conducted against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, in which 230,000 Americans have died, and seen the president himself become infected. First Lady Melania Trump and their son Barron caught the virus too, along with a number of staff at the White House.

In the days before the election on 3 November, Trump urged states to shun lockdowns, whilst continuing his schedule of rallies in battleground states.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTROBERTO SCHMIDT / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTROBERTO SCHMIDT / GETTY IMAGESThe two presidential rivals’ divisions over the coronavirus have been deep, with Mr Biden having said the president’s handling of the worsening coronavirus crisis was an “insult” to its victims.

“Even if I win, it’s going to take a lot of hard work to end this pandemic,” he said. “I do promise this – we will start on day one doing the right things.”

More than 90 million Americans have voted early, many of them by post, in a record-breaking voting surge driven by the pandemic.

Photos are subject to copyright.

By Jessica Stewart on October 28, 2020

“Terry the Turtle flipping the bird” ©️ Mark Fitzpatrick / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Overall Winner, Creatures Under the Water Award. Animal: Turtle, Location: Lady Elliot Island, Queensland Australia.

“I was swimming with this turtle at Lady Elliot Island on the Great Barrier Reef when he flipped me the bird!”

Could you use a good laugh? You’re in luck because there are lots of laughs to be had when looking at the winners of the 2020 Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards. With over 7,000 entries from photographers around the world, it wasn’t an easy decision to narrow the field to a winner. But in the end, it was a photo of a sassy turtle that helped photographer Mark Fitzpatrick win the top award.

It was a case of being in the right place at the right time for Fitzpatrick. The Australian photographer was swimming with turtles off Lady Elliot Island in Queensland when he happened to catch one giving him the middle finger. It’s a hilarious moment that makes you wonder how Fitzpatrick was able to maintain his composure and take the photo.

“It’s been amazing to see the reaction to my photo of Terry the Turtle flipping the bird, with Terry giving people a laugh in what has been a difficult year for many, as well as helping spread an important conservation message,” shares Fitzpatrick. “Hopefully Terry the Turtle can encourage more people to take a moment and think about how much our incredible wildlife depend on us and what we can do to help them. Flippers crossed that this award puts Terry in a better mood the next time I see him at Lady Elliot Island!”

Other category winners include a raccoon half stuck inside a tree (bottom side out), a spermophile singing a tune, and a brown bear knocked out by its own gas. Aside from giving us a good chuckle, the photographs remind us of how special our wildlife is, and that we need to continue to protect it at all costs.

“Social distance, please!” ©️ Petr Sochman / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Think. Highly Commended. Animal: Rose-ringed parakeet, Location: Kaudulla national park, Sri Lanka.

“This photo from January 2020 is the beginning of a scene which lasted approximately one minute and in which each of the birds used a foot to clean the partner’s beak. While the whole scene was very informative, this first photo with the male already holding his foot high in the air was just asking to be taken out of the context…”

“O Sole Mio” ©️ Roland Kranitz / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Affinity Photo People’s Choice Award. Animal: Spermophile, Location: Hungary

“It’s like he was just “singing” to me! She had a very nice voice.”

“Almost time to get up” ©️ Charlie Davidson / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Alex Walker’s Serian Creatures on the Land Award. Animal: Raccoon, Location: Newport News, Virginia.

“The raccoon was just waking up and stretching. We have a raccoon in this tree every so often, sometimes for a night and sometimes for a month.”

“Deadly Fart” ©️ Daisy Gilardini / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Amazing Internet Portfolio Award. Animal: Brown bear, Lake Clark National Park, Alaska.

“A brown bear is lifting its leg to smell after a fart.. then collapses.”

“I had to stay late at work” ©️ Luis Burgueño/ Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: South sea elephant (Mirounga), Location: Isla Escondida, Chubut, Patagonia Argentina.

“South sea elephant in patagonia (Isla Escondida) They adopt very curious gestures!”

“Tough negotiations” ©️ Ayala Fishaimer / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Fox, Location: Israel

“I was came across a foxes den while I was traveling, looking for some nature, in the nearby fields. I spent an entire magical morning with four cute fox cubs. At some point I noticed that one of the cubs start sniffing around, and a seconds after, he pulled this shrew (which he probably hid there earlier) out of the sand and started playing with it. after a while, the fox cub stood on the stone and threw the shrew in the air .. the shrew landed in such a way that it seemed as if they were having a conversation, and he is asking the fox “Please don’t kill me” It’s actually reminded me of a scene from ‘The Gruffalo’ story …”

“Seriously, would you share some” ©️ Krisztina Scheef / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Atlantic Puffin, Location: Scotland, UK

“Atlantic Puffins are amazing flyers and their fishing talents are – well – as you see some do better than others! I just love the second Puffin’s look—can I just have one please?”

“Smiley” ©️ Arthur Telle Thiemenn / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Sparisoma cretense, Location: El Hierro, Canary Islands

“Parrot fish from El Hierro, Canary Islands… among a group of parrot fish I saw this one, with a crooked mouth, looking like it was smiling. I don’t know if it was caused by a fishing hook, or just something hard that it tried to bite. I concentrated on it, and it took me several minutes until I got this frontal shot… and yes, it made my day!”

“I’ve got you this time!” ©️ Olin Rogers / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Think Tank Photo Junior Category Winner. Animal: African lion cub, Location: Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe

“An African lion cub stalks his brother from atop a termite mound.”

“Hide and Seek” ©️ Tim Hearn / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Spectrum Photo Creatures in the Air Award. Animal: Azure Damselfly, Location: Devon, UK.

“As this Azure damselfly slowly woke up, he became aware of my presence. I was lined up to take a profile picture of his wings and body, but quite sensibly the damsel reacted to the human with the camera by putting the marsh grass stem between me and it. I took the shot anyway. It was only later that I realized how characterful it was. And how much the damselfly looks like one of the muppets.”

“Fun For All Ages” ©️ Thomas Vijayan / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Langur, Location: Kabini, India

“Shooting the most common is the most challenging thing. Langurs are very common but waiting for the right movement is very challenging and needs lots of patience. Photography is not about the quantity I consider it more of a quality and a storytelling frame that can put a smile in someone’s heart. In 2014 I had made 15 trips to India in search of a perfect frame out of these trips, in one of the trips I could only get this frame and I am more than happy with this picture – A playful monkey with its family is a special frame for me.”

“Sun Salutation Class” ©️ Sally Lloyd-Jones / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Sea Lion, Location: Galapagos Islands.

“We were surprised to see that Sea Lions actively practice Yoga. Guess they need to get their Zen as well.”

“The race” ©️ Yevhen Samuchenko / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Langur, Location of shot: Hampi, India.

“My friends and I walked in the center of the small town of Hampi in India. There was a bicycle parking nearby. Suddenly a flock of langurs jumped on these bicycles and began to frolic. We were afraid to frighten them away, I started taking pictures from afar, but then we came very close to them and the langurs continued to play with bicycles.”

“It’s A Mocking Bird!” ©️ Sally Lloyd-Jones / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: A Kingfisher, Location: Near Kirkcudbright

“I was hoping a Kingfisher would land on the ‘No Fishing’ sign but I was over the moon when it landed for several seconds with a fish. It then flew off with its catch. It appeared to be mocking the person who erected the sign!”

“Monkey Business” ©️ Megan Lorenz / Comedy Wildlife Photo Awards 2020. Highly Commended. Animal: Pig-Tailed Macaques, Location: Kinabatangan River in Borneo, Malaysia.

“While on a trip to Borneo, I had many opportunities to watch monkeys interacting with each other. These Pig-Tailed Macaques showed me a bit more than I bargained for! Don’t blame me…I just take the photos, I can’t control the wildlife! So many titles came to mind for this photo but I went with the safe ‘family-friendly’ option and called it ‘Monkey Business’.

From CNN

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/10/31/entertainment/gallery/sean-connery/index.html

Legendary screen actor Sean Connery, who put a face to the equally legendary character James Bond, has died, according to his publicist.

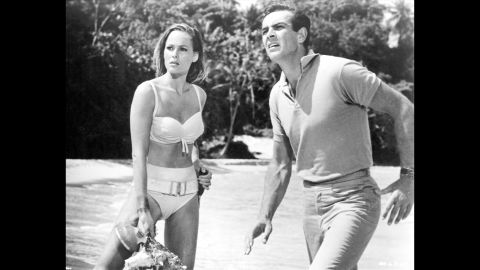

Connery was best known for his role as the swaggering, lady-loving British spy James Bond, a role he played in seven movies, including “Dr. No” and “Goldfinger.” The Edinburgh-born actor, who was a staunch supporter of Scottish independence, also brought to life characters in films such as “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” “The Untouchables” and “The Rock.”

He was 90 years old.

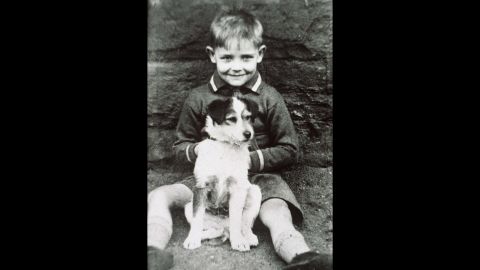

A young Connery poses with a dog. He was born into a working-class family in Edinburgh.

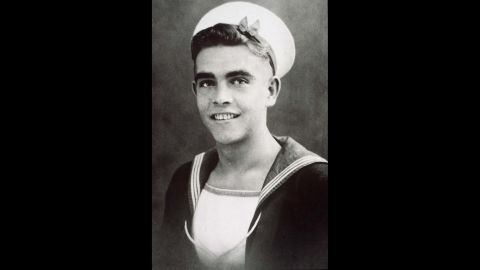

A young Connery poses for a photo. He quit school in his early teens and enlisted in the military.

Connery, number 24 in center, competes in a bodybuilder beauty contest in the 1950s.

Connery is seen with his wife, Diane Cilento, on their honeymoon near Marbella, Spain, in December 1962.

Connery poses for a photo in 1962, the year he would first play James Bond.

Ursula Andress and Connery perform in a scene from “Dr. No,” Connery’s first film as James Bond.

Connery on the set of “From Russia with Love.”

Connery poses as James Bond next to his Aston Martin DB5 in a scene from “Goldfinger” in 1964. Bond is often seen in the movies driving the car at high speed.

Claudine Auger and Connery in a scene from “Thunderball.” Connery’s attractive female co-stars in the series became known as “Bond girls.”

Connery signs autographs at the Cannes Film Festival in France in 1965.

Connery travels with his actress-wife, Diane Cilento, and their children Gigi and Jason in 1967.

Anthony Costello and Connery on set of “The Molly Maguires” in 1970.

Connery rehearses a scene in the 1971 Bond film “Diamonds Are Forever.”

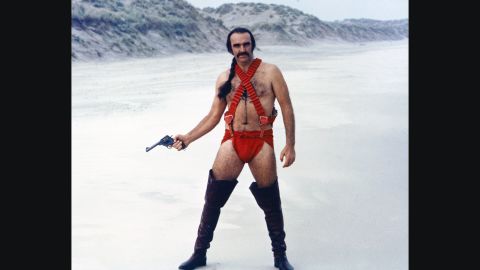

Connery poses for a publicity photo for the film “Zardoz” in 1974.

Connery dances with Kim Basinger in a scene from the 1983 film “Never Say Never Again,” his last film as Bond.

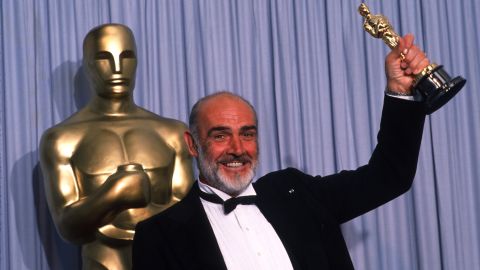

Connery holds up his Oscar for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for “The Untouchables” at the 1988 Academy Awards.

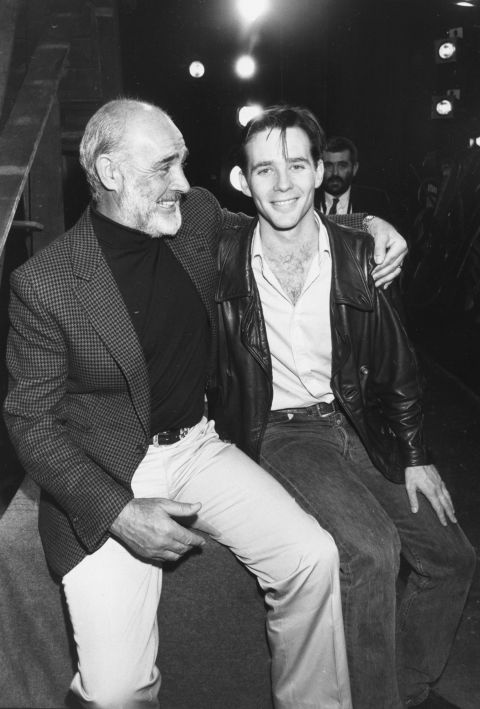

Connery and his son, Jason, are seen on the set of the play “Journey’s End” in 1988.

Harrison Ford and Connery during a scene from “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” in 1989. Connery played Jones’ father as a man who competed with his son for everything — including women.

Connery and his second wife, Micheline Roquebrune, attend a premiere in London.

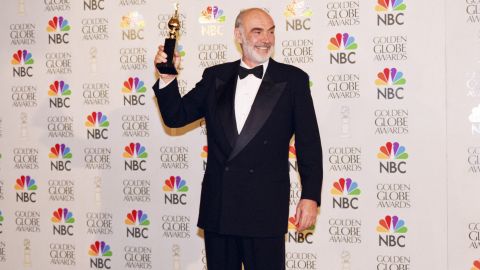

Connery holds up his Cecile B. DeMille Award during the Golden Globe Awards in 1996.

Connery in a scene with Nicolas Cage from the 1996 film “The Rock.”

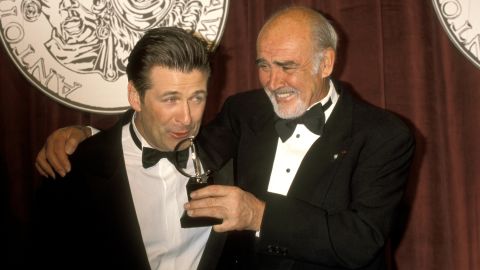

Alec Baldwin and Connery pose for photos during the Tony Awards in 1998.

Connery shows his feet to the crowd on the Hollywood Walk of Fame during his Hand and Footprint Ceremony at the Mann Chinese Theater in Hollywood in 1999.

Sean Connery was among the Kennedy Center Honorees in 1999. From top left, clockwise: Judith Jamison, Connery, Victor Borge, Stevie Wonder and Jason Robards, as they pose following a dinner.

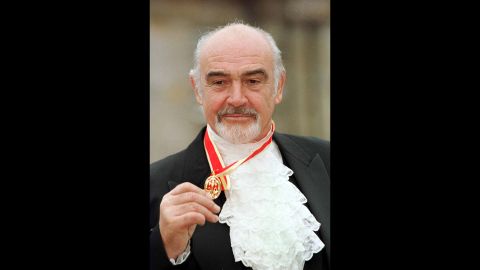

Connery poses for photos in full Highland dress along with his medal after he was formally knighted by the Queen in 2000.

Connery takes a ceremonial kick off during a “Match for Peace” in Barcelona, Spain, in 2005. FC Barcelona played a team comprising Israeli and Palestinian players to support efforts to end the conflict between the countries.

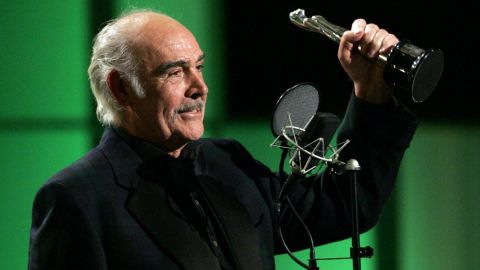

Connery receives the European Film Academy’s lifetime achievement award in 2005.

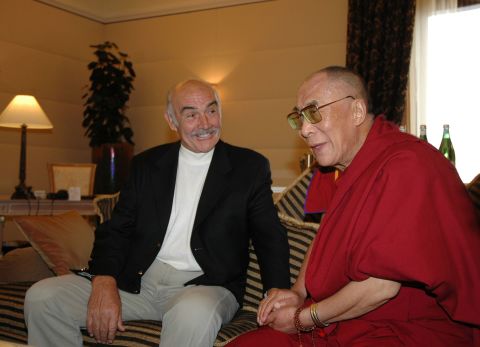

Connery meets with the Dalai Lama in Italy in 2006. The actor’s appeal, partly due to the name recognition of his signature character, made him a global figure.

Connery promotes his new book “Being a Scot” at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in 2008. Connery was a staunch supporter of Scottish independence.

Connery watches a tennis match during the US Open in 2017.

Dharavi contained Covid-19 against all the odds. Now its people need to survive an economic catastrophe.

Normally, Khwaja Qureshi’s recycling facility in Dharavi, the slum in Mumbai, would be no place for three newborn tabby kittens. Before efforts to contain the novel coronavirus idled much of the Indian economy, the 350-square-foot concrete room was a hive of nonstop industry. Five workers were there 12 hours a day, seven days a week, dumping crushed water bottles, broken television casings, and discarded lunchboxes into a roaring iron shredder, then loading the resulting mix of plastic into jute sacks for sale to manufacturers. But during a recent visit, the shredder was silent and the workers gone, decamped to their villages in India’s north. That left the kittens plenty of space to gambol across the bare floor, nap on a comfortable cardboard box, or be amused by the neighborhood kids who came to visit.

Qureshi, a stout, thick-fingered man of 43 whose father founded the operation, mostly ignored his feline workplace companions. He’d been spending his days sitting on a plastic chair, drinking cup after cup of milk tea and chatting with other Dharavi entrepreneurs, all of them part of Mumbai’s fearsomely efficient but completely informal recycling industry, who stopped by to talk business. The consensus was pessimistic. India’s economy is in an historic slump, and less economic activity means fewer things being thrown away—and also less demand to make new products from the old. No one had much hope that things would pick up soon.

The irony is that Dharavi, which has a population of about 1 million and is probably the most densely packed human settlement on Earth, has largely contained the coronavirus. Thanks to an aggressive response by local officials and the active participation of residents, the slum has gone from what looked like an out-of-control outbreak in April and May to a late-September average of 1.3 cases per day for every 100,000 residents, compared with about 7 per 100,000 in Portugal. That success has made Dharavi an unlikely role model, its methods copied by epidemiologists elsewhere and singled out for praise by the World Health Organization. It’s also a remarkable contrast to the disaster unfolding in the rest of India. The country has recorded more than 6.5 million confirmed cases—putting it on track to soon overtake the U.S.—and over 103,000 deaths.

Dharavi’s economic calamity, however, may be just getting started. Its maze of tarpaulin tents and illegally built tenements and workshops have traditionally served as a commercial engine for all of Mumbai, a frenetic crossroads of exchange and entrepreneurship at the heart of India’s financial capital. Before the pandemic, it generated more than $1 billion a year in activity, providing a base for industries from pottery and leather-tanning to recycling and the garment trade. Deprivation abounded, but Dharavi could also be a social accelerator, allowing the poorest to begin their long climb to greater prosperity—and to joining the consumer class that powers the $3 trillion Indian economy. Qureshi’s own family is a case in point. His father was born in the hinterland to a poor tenant farmer but moved to Dharavi to work in a textile factory, getting into the recycling business after he realized the value of the plastic packaging that new spools of thread arrived in.

Led by an energetic municipal manager named Kiran Dighavkar, who was also in charge of the slum’s Covid-19 response, people in Dharavi are now trying to restart their economic lives without seeding new outbreaks. Their success or failure will be an important example for similar places around the world—areas that are home to as much as a sixth of the global population and which no government hoping for a durable recovery from the virus can afford to ignore. Whether in Nairobi’s Kibera or Rio de Janeiro’s hilltop favelas, slum economies are inextricably linked to the cities around them. In some countries their inhabitants account for 90% of the informal urban workforce—an army of construction laborers, small-time vendors, assembly-line helpers, and restaurant servers that developing world metropolises rely on to function. Those jobs are never easy, but they are often preferable to the monotony of rural poverty.

The challenge in Dharavi is to reclaim this vitality safely. “Now we have to live with this disease,” Dighavkar said in an interview at a temporary hospital, one of several he’d established to handle Covid-19 cases. “Dharavi is a hub of activity, and we cannot let it go.”

Dharavi’s modern history dates to the late 19th century, when Muslim tanners, looking for a place to practice their odoriferous trade outside the limits of British-run Bombay, built a rudimentary settlement nearby. By the 1930s it was attracting other migrants: potters from Gujarat, crafters of gold and silver embroidery from north India, and leather workers from the Tamil-speaking south, among many others. All added their own living quarters, building with whatever materials they could find, giving little notice to the fact they were, technically, squatting on government-owned land.

As the Raj gave way to independent India and Mumbai’s population swelled, the teeming slum eventually found itself not on the city’s fringe but near its geographic center. By then, many of its tents and huts had been replaced by structures of brick, concrete, and tile, arrayed around communal wells and powered by electricity from the municipal grid—even though almost no residents had formal land title. There were far too many of them to evict, or ignore, and in the 1970s, vote-seeking politicians began to make small improvements, such as public latrines. By the time the area played a starring role in 2008’s Slumdog Millionaire, soaring housing costs in the rest of Mumbai had even made it attractive to some white-collar workers looking for affordable, centrally located housing.

Meanwhile, Mumbai’s government had begun floating ideas for a redevelopment, one that would replace lopsided squatters’ homes with modern apartments and move factories and workshops into purpose-built quarters, probably elsewhere in the metropolis. But successive consultations, proposals, tenders, and visioning exercises failed to settle on any plan. That was due in part to opposition from residents, who pointed out that even if renovations brought better housing, their jobs might be relocated to distant industrial parks.

Dighavkar, who is 37 and a civil engineer by training, came to Dharavi with modest ambitions. Last year he was named assistant municipal commissioner for G Ward North, a swath of Mumbai that includes the slum. His previous posting was in the historic core, where his signature project had been the construction of a viewing platform in front of Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, an architecturally spectacular Victorian rail hub, that allowed tourists to snap photos without dashing into traffic. He also proudly took credit for building the city’s costliest public convenience, a $122,000 toilet complex on a busy seaside promenade.

With redevelopment plans in flux, Dighavkar’s superiors had little enthusiasm for putting significant money into Dharavi. So in his first months in his new role he focused on the middle-class neighborhoods at its edges, laying new sidewalks and making symbolic changes such as switching the figures on crosswalk signals from male to female.

Dharavi’s first coronavirus case was posthumous. In early April, a 56-year-old resident tested positive after he’d already died. There were only about 2,000 confirmed infections in India at the time, mostly traceable to international travel, and the news seemed to indicate a serious problem. A place with more people than San Francisco, crammed into an area smaller than Central Park, is hardly a promising environment for social distancing. As many as 80 people may share a single public toilet in Dharavi, and it’s not uncommon for a family of eight to occupy a 100-square-foot home. Infections were soon spreading rapidly, prompting the Mumbai government to impose draconian containment measures. Whole streets were sealed off behind checkpoints, with officers on patrol and camera-equipped drones buzzing overhead. With rare exceptions, no one could leave the area, not that there was anywhere to go: The rest of the city, and all of India, were locked down, too, though usually with much lighter enforcement.

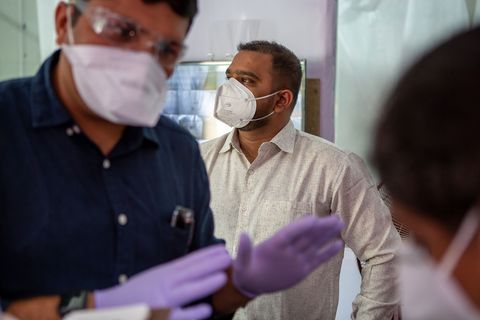

But to Dighavkar, the impossibility of keeping slum residents in their homes quickly became evident. At the very least, people had to come out to use the toilet, to fill water bottles from public taps, and to collect food packets donated by charities. Gradually he and his colleagues developed a more precise approach. Rather than waiting for infected people to announce themselves, the government began dispatching teams of health-care workers to find them, going door to door asking about symptoms, offering free fever screenings, and administering tests to those likeliest to have the virus. They commandeered wedding halls, sports centers, and schools as isolation facilities to separate suspected cases from the rest of the population. Those who tested positive were sent to hospital wards that had been dedicated entirely to treating Covid-19, while contact tracers raced to locate people they’d spent time with.

Some were reluctant to cooperate. Many people in Dharavi work in unlicensed businesses that are in perpetual danger of being closed, and have good reasons to avoid contact with the authorities. But Dighavkar’s workers gradually won their trust, thanks in part to residents returning from quarantine telling of a comfortable stay and competent care. By July the number of new cases had declined to an average of 10 a day, compared with 45 per day in May, although the figure has since ticked modestly upward.

Some scientists have suggested the impressive numbers aren’t entirely the result of public-health measures. Antibody surveys over the summer found that almost 60% of the population in certain Mumbai slums had coronavirus antibodies, indicating that a degree of herd immunity could be at work. But even the most fatalistic virologists credit Dighavkar’s model with keeping mortality low, with some help from a youthful population. At just 270 confirmed deaths, Dharavi has one of the lowest Covid-19 fatality rates of any urban area in India, and methods developed there are now being rolled out across the country as the disease tears through smaller cities.

The apparent containment of the virus in Dharavi, or at least of its worst effects, didn’t spare its people economically. Many have had experiences like those of Valli Ilaiyaraaja, who used to work as a cleaner for three families in a neighborhood near the slum, and said none would allow her back even after the national lockdown ended in June. Their apartment buildings had banned entry to outside help, out of fear that cleaners and cooks would bring the virus with them. Similar policies remain in place across the city.

This has resulted in some inconvenience for Mumbai’s middle and upper classes—one local company had to suspend sales of dishwashers because of an overwhelming volume of orders. But it’s a financial catastrophe for people like Ilaiyaraaja. She and her three young daughters now depend entirely on her husband, who lost his job as a welder during the lockdown and is making just 100 rupees ($1.37) a day loading trucks. That’s not enough to pay for the cost of traveling to their home village in South India, where they could live rent-free, nor to cover school tuition for the girls. So the family is in limbo, waiting both for the economy to pick up and for the stigma attached to slum dwellers to fade. “We are fed up with this virus,” Ilaiyaraaja said in her tiny tenement apartment, two of her daughters sitting shyly by her side, “and with waiting for this nightmare to be over.”

On a muggy summer day, seven anxious-looking people, all wearing masks, stepped off a minibus and into a large vinyl tent that had taken over a parking lot on Dharavi’s outskirts. The tent housed a 192-bed field hospital for Covid-19 cases and had been carefully designed to triage incoming patients without letting them spread the virus. Past the double doors the group entered a spacious holding area monitored by a thermal camera on a tripod. Just behind, in a sealed-off observation booth, Dr. Asad Khan issued instructions through a microphone while observing the camera feed on a monitor.

When the system detected a fever, the monitor was supposed to show a red box around a patient, while normal temperatures would prompt a green box. The trouble, though, was that all the boxes were green—not something a physician greeting confirmed coronavirus carriers would expect to see. This prompted Khan to query the new arrivals on why they’d been brought to his tent. A young man stepped forward as the group’s unofficial spokesperson, and after some back and forth, Khan learned that none of them had even been tested for the virus. They were contacts of positive cases and were supposed to have been taken to an isolation center, not the hospital. A few minutes later they climbed back into their vehicle and were driven away.

Dighavkar, watching from inside the booth, was pleased. A bus going to the wrong facility was a harmless mix-up, but letting seven potentially healthy people interact with infectious Covid-19 patients would have been a disaster. The thermal camera and Khan’s questioning had prevented that outcome—evidence, to Dighavkar, that the system was working. “This is our own invention,” he said of the camera-and-interview process. “This is the procedure. Contactless entry.”

He was conscious, though, that a system sufficient to contain the virus with the economy halted could be severely tested by the resumption of more activity. By July some parts of Dharavi were coming slowly back to life. Beggars had returned to intersections, though usually wearing masks as they shuffled from car to car. Fabric wholesalers had rolled up their steel shutters, while corner stores were again places for groups of local women to meet and chat.

What worried Dighavkar was the prospect of reopening factories—cramped, poorly ventilated places where laborers spend hours on end, elbow-to-elbow. “Once the factories start again, maybe we’ll get more cases,” he said in his office. In front of his broad wooden desk, someone had set up neat rows of chairs to allow subordinates to gather before him like students at an assembly. “We have to make sure safety measures are taken.” His most urgent priority was to get as much protective gear to workers as possible. The municipal government had been distributing masks, gloves, face shields, and sanitizer to factories for free, turning a blind eye to illegal operations in the hope that owners would accept help. Regardless of their official status, “we are here to take care of them,” Dighavkar said.

The future of Dharavi’s manufacturing sector may look like International Footsteps, a factory that makes sandals for Western mall brands such as Aldo. To get there, you must first turn off one of the slum’s raucous commercial drags and into a lane of decrepit buildings covered in tarps and corrugated steel sheets, which opens after a little while into something of a public square. There, if you skip between a puddle of foul water and a dead rat, then duck beneath a tangle of electrical wires, you’ll come to a dark, damp tunnel leading to what feels like a different world. In a pristine marble hallway, a multilingual sign asks visitors to apply some hand sanitizer from a dispenser on the wall. Just beyond is a bright workshop, where during a recent visit eight artisans sat cross-legged at workstations spaced about two feet apart—considerably less jammed-in than they would have been before this year. Managers had cleared out some upstairs storage space to allow more distance between each employee, and all of them were wearing disposable smocks, masks, and plastic face shields, purchased at the company’s expense. The protection raises costs, “but it’s required for the safety of everyone,” said floor manager Vijayanti Kewlani, who’d donned the same gear.

The problem, for International Footsteps as well as other businesses in Dharavi, is that “everyone” isn’t who it used to be. Only about two-thirds of the slum’s people are formal residents; the rest are rural migrants who traditionally slept on factory floors or shared rented rooms, returning to their hometowns a few times a year. But there was no government help to cover wages during the national lockdown, and it caused a severe crisis for these laborers. With snack bars and mess halls shut, even those who could afford food struggled to find enough to eat.

Many had little choice but to go home, a journey that had to be made on foot, because the government had suspended train and bus services to contain infections. It was likely the country’s largest forced migration since Partition, the violent 1947 division of India and Pakistan—and had the unintended result of spreading the coronavirus deep into rural areas. With the global economic slump depressing activity in cities, a large proportion of the migrants have stayed in the countryside.

International Footsteps tried to keep connected with its workers, paying them 80% of their salaries for the first month of lockdown and 60% for the second. It also offered to cover the cost of transportation back to the city and is looking into securing more spacious housing—maybe even with the luxury of an attached toilet—for staff who return. But only 30% of its personnel have resumed their jobs, mostly Dharavi locals, leaving the company well short of the numbers it might need to fill large orders.

Suraj Ahmed was one of the few who’d come back—in his case from a small village in Uttar Pradesh. He couldn’t afford to live in the room he’d been sharing with two co-workers, because neither had yet returned. So the company was letting him stay on the premises for free, until he could find a more permanent arrangement. The visible precautions in the factory made him feel safer, Ahmed said as he attached a finely worked leather strap to the top of a new sandal, his wiry beard peeking out from under his mask. But he was more impressed with the 10% raise he’d received for coming back to work. “I have to earn a living,” he said.

Despite its absent workers and stepped-up protective measures, Dharavi could still provide an extremely hospitable environment for the virus—particularly if a rush of returning migrants reintroduces it at large scale. The only solution, Dighavkar says, is “screening, screening, screening,” an unrelenting effort to track down infected people and isolate them from the community. “It will be part of our continuous process from now on.”

The front line of Dighavkar’s plan will be made up of women. His department has assembled an army of almost 6,000 health workers and volunteers, mainly from Dharavi itself, who’ve been given thermometers, pulse oximeters, and basic training in how to spot Covid-19. The idea is to send them house to house, day after day, in continuous sweeps of every part of the slum, and to keep doing it until the end of the pandemic. It’s a substantial commitment of resources, but the human and economic toll of a renewed outbreak would be far larger.

One morning in July, after one of the heaviest monsoon rainfalls Mumbai had seen in years, about a dozen of these women gathered at a public hospital to collect their addresses for the day and suit up in protective gear. Some undertook a tricky maneuver that involved pulling the hems of their saris up and back between their legs, tucking the fabric behind their waists, to step into the white coveralls they’d been issued. After drawing the hoods over their hair, they looked a little like snowmen.

Sunanda Bhoyar was more practically attired, in a block-print tunic over billowy pink trousers, and donned her suit with ease. She was one of the group’s few professionals, a registered nurse assigned to guide the less-experienced workers. She soon set off into the heart of Dharavi’s residential quarter, a warren of footpaths and alleyways often too narrow for a pair of people to walk abreast. There was almost no sunlight, the result of haphazard additions that had pushed the buildings on either side to structurally questionable heights.

Bhoyar knew the way and soon found what she was looking for: the home of an elderly couple who’d just tested positive and were being treated in hospital. She told the young man who answered the door that everyone who lived in the house needed to go to a quarantine center for observation and testing. But the man, who said he worked as a sales manager at an insurance company, making him prosperous by local standards, was reluctant. He and his three brothers had four rooms, he said—plenty of space to isolate at home. Bhoyar wasn’t having it. She ordered everyone’s hands marked with indelible ink—also used in India to prevent people from voting twice in elections—to ensure they’d be brought to quarantine.

Soon, Bhoyar approached a neighbor, who was skeptical that he was at risk, claiming that he and his wife didn’t even know the people who’d been infected. Contact tracing suggested otherwise. Bhoyar patiently explained that the man’s 9-year-old daughter was friends with one of the brothers’ children, and often visited their house to play. The neighbor’s family wouldn’t have to quarantine, she said, but would be visited again to see if anyone had developed symptoms. As Bhoyar spoke, a city sanitation worker stepped forward to spray the house with disinfectant. Bhoyar soon gathered up her entourage of assistants to move on.

This kind of tedious work has none of the technological glitz of an innovative treatment or the silver-bullet promise of an effective vaccine. But as the rain started to pick up again, Bhoyar said she was convinced that, in Dharavi, it would be enough to keep the virus at bay. “Precaution will be our key focus going forward,” she said—“social distancing, awareness related to hygiene, fever screening, and sanitization.” Even with the massive slum slowly coming back to life, Bhoyar added, “I’m not really scared.”

From gamespot/By

There are all kinds of horror-tinged media to choose from nowadays, but games may be the most chilling medium of all due to the level of immersion and interactivity they impart. If you’ve ever sat in a dark room with headphones and played something like Silent Hill or Resident Evil, you know that unique feeling of terror we’re talking about. And god forbid you need to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Horror games aren’t exactly for the weak of heart.

But as Halloween approaches, there’s no more fitting genre for the season, and luckily, there are a wealth of horror games out there well worth your time. The genre had humble beginnings in the late ’80s, with a wave of fantastic games coming out in the three subsequent decades. And thanks to the rise of indie games, there are more scary games out now than ever before.

In 2020 we’ve seen some excellent horror games released, such as Capcom’s follow-up to its Resident Evil 2 remake, Resident Evil 3. But even more are yet to come; we’re still looking forward to horror games like The Dark Pictures: Little Hope and Amnesia: Rebirth to keep genre fans busy this fall.

Whether you plan to work your way through your horror backlog on your own or invite friends over to experience the jump scares with you, we’ve got you covered this Halloween season and beyond. We’ve gathered a list of the most terrifying and memorable games every horror enthusiast should experience this Halloween season. Genre classics like Silent Hill 2, Resident Evil Remake, and Dead Space are represented here, but you’ll also find more surprising and modern choices interspersed throughout. Regardless of their notoriety, the horror games we highlight below (listed in no particular order) are all ones that left us with lasting memories.

Which horror games will you be playing this fall? Shout out your favorites in the comments below.

After creating a phenomenon with Amnesia: The Dark Descent and following it up with the existential horror of Soma, Frictional Games is going back to the series that put them on the map with Amnesia: Rebirth. Taking place in 1937, Rebirth’s aesthetic finds itself somewhere between the Victorian-era castles of The Dark Descent and the hyper-futuristic underwater facility of Soma. Of course, with this being a Frictional game, nothing’s as it seems, and even in the release date trailer, there are signs we’re in for an even wilder and scarier ride than we might think. Amnesia: Rebirth is set to release October 20, which is a great time to get some good, new scares in on Halloween. — Suriel Vazquez

Horror is more fun with friends. Unlike other action-oriented multiplayer horror games like Left 4 Dead and Dead by Daylight, Phasmophobia capitalizes on the lighter social elements of the genre, essentially turning the business of ghost hunting into a party game. Don’t take this to mean the four-player co-op game isn’t played straight–on the contrary, Phasmophobia is a serious paranormal investigation simulator, complete with a sanity meter, an arsenal of tools and surveillance equipment to monitor ghostly activity, and a checklist of objectives to guide you in testing and finally identifying whatever entity is haunting your assigned location. But between its charming early access jank and clever use of voice recognition, a single game of Phasmophobia has the potential to shift from a goofy seance with friends to survival horror at the flick of a switch—sometimes literally.

Working together with up to three other players, you’ll need to navigate haunted homes, farmhouses, and even a school, setting up cameras and other devices in order to monitor, coax, and even aggravate whatever spirit or demon is lingering in the area. Cameras let you detect paranormal activity remotely, while a handheld EMF reader lets you scan for atmospheric changes as you explore. The entity might leave an angry message scrawled in a notebook left in one room while you join your friends scanning for fingerprints or a drop in temperature in another part of the house. A ouija board even lets you communicate with the ghost directly, though sometimes shouting its name or even swearing at the spirit using a microphone is enough to taunt it out of hiding.

This is where some of the party game antics come in. While the stated goal is to collect enough evidence to reasonably guess the nature of the entity haunting the area (poltergeist? demon? banshee? the list goes on), all of the technical setup and ensuing tests to lure some of that evidence out is where the fun of Phasmophobia really lies. Bursting into a room and calling a ghost a dumbass. Hanging out in the surveillance truck out back and watching a live feed of your friends scrambling around in the dark after the front door mysteriously locks. Getting completely owned by a ghost (complete with silly ragdoll physics), then becoming a ghost yourself and following your friends around as they struggle to complete the mission with one person down. While it won’t actually let you play as the ghost and freak out your friends, Phasmophobia is still very, very early in development—at this stage, who knows what can happen? — Chloi Rad

It’s an Early Access title at the moment and thus feels a bit incomplete, but don’t sleep on World of Horror, a lightly animated text adventure that’s all spooky vibes, all the time. Inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft and horror manga artist Junji Ito, the roguelite game sends you out into a strange town beset by twisted people and supernatural horrors. World of Horror feels like you’re playing through one of Ito’s strange short stories, where you might search through a school for a murderous, scissors-wielding substitute teacher with a carved-up face, or investigate the apartment of a researcher who was extremely interested in eels–but, like, in an evil way.

Each of your investigations takes you through various locales, where you’ll meet allies, find weapons, and engage in text-based combat with creatures, all in an effort to discover what eldritch horror is trying to be born into the world so you can put a stop to it. World of Horror is constantly creepy, often funny, consistently challenging, and always compellingly weird, and especially if you like Ito’s works and fresh spins of Lovecraft tropes, you shouldn’t miss it. — Phil Hornshaw

This year’s Resident Evil 3 remake shows a different side of the infamous outbreak we first saw in Resident Evil 2. After surviving the Spencer Mansion incident, Jill Valentine must now escape zombie-ridden Raccoon City while being pursued by the bloodthirsty Nemesis. RE3 requires resource-management, puzzle-solving, and a cool hand to take out the zombies and other monsters that threaten your life. It’s definitely a more brief experience than the Resident Evil 2 remake, but Resident Evil 3 is still worth playing for fans of Resident Evil, horror, and zombies. And once you’re finished your first playthrough, you can partake in victory laps with unlocks like more powerful guns, infinite ammo, and more. — Mat Paget

Until Dawn developers Supermassive haven’t quite found a hit on that game’s scale since 2015, but they’ve slowly been getting their groove back. The first part of The Dark Pictures Anthology, Man of Medan, had a lot of what made Until Dawn shine, so we’re hopeful Little Hope improves on the formula and has some great scares of its own. It’s also primed to be a good Halloween game, releasing on October 30 and likely being short enough to get through in a single sitting with a group of friends — Suriel Vazquez

The remake of a horror classic, Resident Evil 2 released last year and was one of our top picks for Game of the Year. The remake doesn’t change the story of the original, for the most part: You still get the choice to play as either Leon Kennedy or Claire Redfield as they make their way through zombie-infested Raccoon City. The storylines and settings for each character are similar, but there are unique side characters and other differences that make playing each character’s path worth it. Plus, it’s not that long–only about 3-5 hours for each campaign.

Resident Evil 2 is a brilliant remake that improves and expands upon the original. The creepy atmosphere left me constantly on edge, holding my breath as I turned every corner, but it balances that fear with a huge sense of satisfaction at solving challenging puzzles and taking down enemies without exhausting all my ammo. While I didn’t find Resident Evil 2 quite as frightening as Resident Evil 7, it’s still one of the best horror games out there, and I was enthralled by its story until the very end. — Jenae Sitzes

Until Dawn has become a classic among story-driven games. The survival-horror adventure follows a group of friends on a winter getaway to a snowy mountain lodge, where, one year prior, two of their friends disappeared and were never found. It’s the stereotypical setup for a slasher film, complete with flirty teens and a masked stalker on the loose, but the story takes some unexpected and unforgettable turns along the way. Most notably, Until Dawn is driven by player choice, and the consequences of your choices are deeply felt throughout the entire game. On your first playthrough, there are no redos if your action gets someone killed–only in subsequent playthroughs can you go back to specific chapters to make a different decision.

Because the story branches off in so many directions and has multiple endings, there’s a ton of replayability to Until Dawn. While technically a single-player game, Until Dawn is equally fun to play with a group of people. While a bit long for a single session–it’ll take you eight or nine hours to complete–you could easily break Until Dawn into two or three sessions and play through it with friends, with each person choosing a character to control and passing the controller back and forth. Having played it both alone and with friends, I can attest that it’s fun to experience over and over, and there are still characters I haven’t figured out how to keep alive (I refuse to look it up). It’s not on the same level as something like Outcast or P.T. in terms of scariness, but there are some truly terrifying moments in Until Dawn I’ll never forget. — Jenae Sitzes

Red Dead Redemption quickly became one of my favorite games of all time when it was released back in 2010. This was thanks in most part to the wonderful setting, quirky yet lovable characters, and increasingly engaging story. I was ready to take any excuse to spend more time in that world, and you can bet your butt I was excited for a zombie-themed expansion. Undead Nightmare is supposed to be a bit more silly and nonsensical than scary, but I don’t think a single game has unnerved me as much as it. Seeing the familiar Wild West turned into a desolate, fog-filled wasteland of zombies was shocking.

It was as close as I’ve felt to actually experiencing a zombie apocalypse breakout in my hometown. Even my family had been turned, and though John Marston was reacting in a humorous way, I couldn’t help but be totally stressed out by the entire situation. And these zombies aren’t the slow and lumbering type you find in the halls of Resident Evil 2’s police station: they sprint right at you, make the absolute worst noises, and need to be shot in the head. All of this, and that very sad Sasquatch mission, made me feel incredibly uneasy in a world I had fallen so much in love with.

Red Dead Redemption and Undead Nightmare are both playable on Xbox One, thanks to Microsoft’s backward-compatible program. There’s even a 4K patch for the game on Xbox One X, which looks fantastic. — Mat Paget

Amnesia: The Dark Descent, its expansion, Justine, and the sequel, Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, comprise what is still one of the best horror franchises of all time. You can grab all three of them in the Amnesia Collection, available on the PlayStation and Xbox stores. Amnesia is undoubtedly the series that ignited my love of the horror game genre, and like many, I first experienced the game through Let’s Plays by a then-little-known YouTuber called PewDiePie. It’s terrifying enough to watch someone else to play, but getting behind the screen yourself is another experience altogether.

Released in 2010, Amnesia: The Dark Descent follows a man named Daniel, who wakes up in a dark castle with no memory of who he is, aside from his name. In exploring the castle, Daniel must fight to maintain his sanity while putting together pieces of his past and avoiding the dreadful monsters that lurk in the shadows. The first-person survival horror game was followed by a 2013 sequel, A Machine for Pigs, that begins with a wealthy industrialist waking up in his London mansion with (once again) no memory of the past few months, only the feeling that something is terribly wrong. If Amnesia has somehow flown under the radar for you over the past decade, then wait for a dark night, grab some headphones, and dive in. — Jenae Sitzes

Metro Exodus isn’t strictly a horror game. There aren’t many jump scares, there are no re-animated corpses, and you spend a lot of time on a train chatting with your comrades. What Metro Exodus does have is dark, cramped corridors oozing with a foreboding atmosphere. Sure, Exodus also has a lot of open areas, but some of the most terrifying moments are when you’re trapped in the metro, scrounging for supplies, while avoiding irradiated beasts. — Jake Dekker

With Little Nightmares 2 confirmed to release on February 11, 2021, there’s no better time to play the original. Little Nightmares is a Tim Burton-esque puzzle-platformer first released in 2017 that follows a small, hungry child in a yellow raincoat known only as Six. The child is trapped in a horrifying, mostly underwater island location called the Maw, which is home to numerous strange and deplorable creatures. From a long-armed blind janitor to a chilling, shadowy Lady, Six must avoid capture while navigating her way out of the Maw.

Little Nightmares is far scarier than you might expect–I was on edge during my entire playthrough. Like Playdead’s Limbo or Inside, Little Nightmares has no dialogue, letting the creepy environments and tense atmosphere drive all of the suspense. It culminates in an ending that, while a bit open-ended, is definitely satisfying. The game has also received three DLC chapters, and you can get the whole experience in Little Nightmares: Complete Edition. — Jenae Sitzes

A lot has been said about Silent Hill 2, so I’ll spare you any overt critical analysis I have on this beloved survival-horror sequel and instead share with you why this game still rocks. The premise alone should be enough to captivate you. As the widowed James Sutherland, you travel to the foggy town of Silent Hill in search of your dead wife, who has somehow managed to send you a letter. As a middle-schooler (yes, I played this game in 8th grade), Silent Hill 2’s story was like nothing else I had encountered. There were no action heroes, explosions, or convoluted government conspiracies. Just a crippling sense of dread, an eerie atmosphere, and intriguing characters that kept my hands glued to my PS2 controller.

Silent Hill 2 expertly handles its myriad horrors, pulling you in with disturbing creatures, clever puzzles, and haunting sound design. I can’t help but be in awe of how well it stands up whenever I revisit the game every few years. Its Historical Society area remains one of its crowning achievements and one of horror gaming’s most expertly designed environments, brilliantly handling tense foreboding with unexpected pathways and puzzles. There are some slow moments interspersed between its most terrifying ones, but they’re never enough to detract from the chilling horror and thought-provoking storytelling on display.

If you haven’t played Silent Hill 2, you’re in for quite a spooky adventure. It’s one of the genre greats for a reason, and it only continues to stand the test of time. You can buy it as part of the Silent Hill HD Collection for PS3 and Xbox 360; fortunately, it can also be played on Xbox One due to backward-compatibility. — Matt Espineli

Red Barrels’ Outlast has always stood out to me for how the game presents its world. Mount Massive Asylum is blanketed in absolute darkness, so the only way to see where you’re going most of the time is by using the night vision function on protagonist Miles Upshur’s video camera.

Because I’m terrified of the dark, I use the camera all the time, and this transforms everything I see into a murky green where faraway environmental details aren’t clear and enemies’ eyes shine with a ghoulish glow. Also, this mechanic forces me to explore–batteries need to be found to keep the night vision function on the camera working–and Outlast’s chilling soundtrack makes those unscripted moments of searching very tense.

Looking for batteries isn’t even the scariest part of Outlast, though. It’s the inhuman Variants that create most of the game’s scares. Desperately running through an insane asylum while cannibalistic twins, a scissor-wielding mad scientist, and a seemingly unkillable monster chase after Upshur is terrifying. The worst of these Variants, Eddie Gluskin, appears in Outlast’s Whistleblower expansion. Gluskin, aka The Groom, is a deranged serial killer who mutilates his male victims’ genitalia in order to create the “perfect wife.” Watching what he does–in first-person I might add–to the DLC’s protagonist, Waylon Park, haunted me for days, and is still nauseating to even think about. –

If you buy Outlast, you might as well pick up the Outlast Trinity bundle, which includes Outlast, its Whistleblower DLC, and Outlast 2 (which is also very good). – Jordan Ramee

Three years after Resident Evil 4 squeezed new scares from one of gaming’s best horror series, Visceral Games might have perfected the third-person survival horror formula with Dead Space. Players control engineer Isaac Clarke as he and a rescue team land on a city-sized spaceship to find out why it’s not responding to communications. They quickly discover the reason is that the ship has been overrun by monsters that used to be its crew, which are nearly impossible to kill unless players use various sci-fi mining tools to hack off the creatures’ limbs.

Dead Space is a perfect confluence of modern sensibility and old-school survival horror, pairing fantastic graphics and gameplay, specifically its limb-cutting mechanics, with slightly uncooperative controls and the desperate hunt for items to keep Isaac healthy. The game uses everything at its disposal to scare you. Its industrial setting pairs with sound design that makes you constantly feel like you’re not alone, and every surface is covered in air vents perfect for delivering popcorn-tossing moments as lethal mutated creatures come squirming out, straight at your face. Visceral tops it off with a spooky story that combines Alien, Children of the Corn, and Evil Dead.

Developed for Xbox 360, PS3, and PC, you can also play Dead Space on Xbox One via backward-compatibility. — Phil Hornshaw

Devil Daggers may not be a traditional horror game by any means, but that makes it no less scary every time I play it. It throws you into a dark arena and tasks you with eliminating waves of flying skulls, disgusting, multi-legged beasts, and other demonic monstrosities.

There is no winning in Devil Daggers; death is inevitable, whether that comes after 10 seconds or 100 (if you’re good). It’s minimal in terms of visuals and sound; there’s no music to accompany the onslaught of enemies. Instead, enemies produce terrifying but distinct noises. This serves to assist you by letting you know where enemies are, but it also creates an inescapable sense of dread as these horrifying monsters box you in. I find it hard not to jump out of my seat when I turn and see that I’m face to face with a flying horned monster.

It’s unusual that a game designed around high score runs evokes fear, and the threat of failure is undoubtedly part of what makes Devil Daggers so tense. But it’s the combination of this tension with the haunting imagery and sounds that create a legitimately terrifying experience. — Chris Pereira

I’ll admit to being the perfect mark for Slender: The Eight Pages when it was released for free in 2012. The tiny, minimalist Unity experiment by developer Mark Hadley capitalized on peak Slender Man interest, expounding on the Internet-born folklore creature that was already doing a phenomenal job of absolutely creeping me out. Hadley’s little game was a tightly made little nightmare: you’re exploring a small, darkened park from a first-person perspective, and you’re being hunted by a supernatural creature that you can’t even look at without dying. Players try to gather eight pages from around a park, which detail some other poor victim’s descent into madness, while the thing keeps appearing in front of you, ever closer. It was a perfect storm of jump scares, ambient dread, and a spooky creation of the zeitgeist at the height of its power.

Slender: The Arrival expanded the game with multiple levels, a full story and prettier graphics to fully realize Hadley’s original concept. It didn’t change the core principle of being hunted, with nothing to help you except fleeing in desperate terror, and hoping that looking away from what stalks you might be enough to save you a few moments more. — Phil Hornshaw

To play Resident Evil 7 is to willingly put yourself in an inhospitable environment. The decrepit mansion where the game begins is filthy, with peeling, yellowed wallpaper, broken drywall, and garbage littering the scarred wooden floor. Wind blows through the cracks in drafts, emitting a low, constant howl. The kitchen, scattered with moldy food and unidentifiable skeletal remains, is unspeakable. You can almost smell the rot.

This is not a place you want to be–and that’s before you meet the family that lives there. There’s the dad, who stalks after you even after you’ve killed him numerous times. Mom doesn’t bat an eye when he severs junior’s hand at the dinner table. Somehow even worse is grandma, a catatonic woman in a wheelchair who can appear and vanish any time and anywhere when you’re not looking.

The horror game improves on the best aspects of the series, while throwing out everything that had grown stale in recent installments. Playing Resident Evil 7 is a thrilling, crazy, scary-as-hell experience. And if you think it’s terrifying on a TV screen, you gotta try it in VR. — Chris Reed

The Xbox 360 had a generally strong launch lineup, despite lacking a killer app like Halo. There was a Majora’s Mask-lite in Kameo: Elements of Power; sports games like Amped 3 and Madden, and for those who passed on the heavily flawed, but creative Perfect Dark Zero, Call of Duty 2 was there to satisfy action fans when WWII shooters were in their prime. With other titles with mass appeal like Tony Hawk’s American Wasteland or Gun, who had time for a psychological horror game?

That juxtaposition between Condemned: Criminal Origins and the rest of the launch lineup was perfectly clear in the music of the title screen. Half Se7en, half Shutter Island, you play as detective Ethan Thomas, who has to track down a serial killer to prove his innocence after his partner is murdered. Along the way, you’re attacked by rattled-up drug addicts and hallucinations of demons who strategically flee, hide behind corners, and fight back in the game’s surprisingly effective first-person melee combat.

What made Condemned such a memorable horror experience was the feeling of being alone in the grittiest, most desolate parts of town, with intimate combat against people who hated you. You could hear them seething around corners, flanking you in the darkness, and that was all before the game throws demonic hallucinations at you. Sprinkle in a memorable final boss, a couple of solid jump-scares, one of the best uses of Xbox achievements in requiring you to forgo using guns, and a level set in a mall with walking mannequins that culminated in one of my favorite video game moments, and you’ve got a horror classic. Not bad for a launch-title. — Nick Sherman

2014’s Alien: Isolation was a bit of tough sell as a horror game. After spending many years as disposable cannon fodder in other Alien games, most notably in Aliens VS Predator and Aliens: Colonial Marines, the Xenomorph was elevated to boss status in Creative Assembly’s survival horror FPS. Serving as a sequel to the original film, it moved away from the shooting galleries and action-horror from previous games, and honed its focus on dread, anxiety, and fearing the lone alien creature that stalks the halls of Sevastopol Station.

As a deep admirer of the original Alien, more so than the sequel Aliens, I longed for the day where we could get a game more influenced by the first film–with its quiet moments of dread and low-fi sci-fi aesthetic in full swing. What I appreciated most about Alien: Isolation was that it not only respected the original film, but it also fully understood what it made it so scary. As you’re desperately scavenging for supplies throughout the corridors, those brief moments of calm would almost inevitably lead to situations where you’ll come face to face with the Alien, who is all-powerful and cunning in its approach to slay any human that comes across its path.

For more of my thoughts on Alien Isolation, check out my retrospective feature discussing why the game is still an unmatched horror experience. — Alessandro Fillari

Don’t judge a visual novel by its cover. Doki Doki Literature Club looks like a simple anime-inspired visual novel packed with tropes; you have a love triangle (or quadrilateral?), the tsundere, the shy one, and the childhood friend as a potential love interest all thrown into a high school club. While the free-to-play game is front-loaded with your typical story progression, it’s expected that you make it past a certain point where things really pick up.

Take note of the content warning presented upfront, as Doki Doki Literature Club uses sensitive subjects and graphic visuals throughout its narrative. It’ll subvert expectations in clever and terrifying ways that can be either subtle and in-your-face. Since this is a PC game, it has the unique ability to be meta; breaking the fourth wall is used to great effect and a few secrets get tucked away within the game’s text files. There are a few moments that allow the player to impact progression, such as dialogue options or choosing which of the club members to interact with at certain moments. But that’s all in service of building you up for when the game reveals its true nature. Even the wonderfully catchy soundtrack gets twisted to create an unsettling atmosphere.

It’s hard to communicate exactly why Doki Doki Literature Club is one of the most horrifying games because it relies heavily on specific story beats and meta-narrative events, and we wouldn’t want to spoil the things that make it so special. You’ll just have to experience it for yourself. — Michael Higham

When Resident Evil first hit the Playstation back in 1996, it revolutionized video game horror and created a new sub-genre in the process–survival horror. Its GameCube remake in 2002–and subsequent remaster for the PS4, Xbox One, and PC–utilized improved graphics and lighting to greatly enhance the haunting atmosphere of the first game.

You have the option to play as one of two STARS members (elite police officers), who have come to a mansion investigating a number of strange murders. Unbeknownst to them, this mansion is home to a number of illegal experiments operated by the Umbrella Corporation, leading to zombified humans and creatures attacking the STARS.

The entire game takes place from fixed camera angles, and you never know what’s on the other side of the door, or around each corner, meaning you’re just moments away from walking into a scare. You’re given limited ammo and even a limited number of opportunities to save your progress, and this formula works perfectly in tandem with the foreboding atmosphere.

In one particular moment, I hadn’t saved in hours and was running through a room I’d revisited multiple times in the past with 0 health left–when suddenly zombie dogs decided to jump through the windows scaring the crap out of me. A room I thought was safe had betrayed me at the worst time. This moment alone is easily one of the most impactful scares I’ve ever had playing a game and cements Resident Evil as a mastercraft in horror video games. It’s available as part of the Resident Evil Origins Collection, which also gets you Resident Evil 0. — Dave Klein

Eternal Darkness took the concept of survival horror–already well-established by games like Resident Evil, Clock Tower, and Silent Hill–and added a brand new element designed exclusively to screw with the player: the sanity meter.

Alexandra Roivas returns to her family’s estate after discovering her grandfather has been murdered. The police have found nothing, so she decides to look for herself, and finds a secret room with a book… the “Tome of Eternal Darkness.” The game then takes place in multiple timelines and locations, with players choosing who they want to follow as characters battle with, or are corrupted by, ancient artifacts and the Eternal Darkness.

This allows the game to utilize a vast array of settings for its horrors, as well as having every character affected by a sanity meter, which slowly drains if players are spotted by enemies. Sanity effects range from statue heads following you, to weird noises and strange camera angles. In one particular instance, I went to save my game, only to find the game telling me it was deleting my save. I jumped off of my couch, ran over to my GameCube to turn off the game, only to realize the game was screwing with me, and my save wasn’t being deleted. You win that round, Eternal Darkness… you win that round. — Dave Klein

In the years since the release of the first game, the Five Nights At Freddy’s series has gone from popular YouTube Let’s Play game to massive phenomenon. As gaming’s Friday The 13th, the horror series manages to get another sequel, even when people are just experiencing the previous game. While the franchise has spiraled out in a big way, the original game still manages to turn a mundane job into nerve-wracking nightmare scenario. As the late-night security guard for Freddy Fazbear’s Pizzeria, your job is to make sure no one breaks into the place, and to ensure that the walking animatronic puppets don’t murder anyone–namely you. That second part is important.