Lebanese Artist Creates Powerful Sculpture From the Ashes of Beirut Port Explosion [Interview]

Though several of her sculptures, all made with upcycled materials, were destroyed by pro-government activists, Nazer was not deterred. In fact, her desire to create art that speaks to the masses only grew and has culminated with this untitled sculpture of a woman proudly standing at the port. Though the sculpture has now been moved for fear that it will be destroyed, Nazer is hopeful that with proper funding she’ll be able to create a larger, permanent memorial, to all those who were lost or injured in the explosion.

We had a chance to chat with the Lebanese artist about what motivated her to create this revolutionary art and the symbolism behind this powerful sculpture. Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

What drove you to begin creating these sculptures?I used to work with the United Nations, then I quit my job to be an artist because I felt the need—it was not the want, but the need—to paint and to do art. So I quit my job around 2016 or 2017. I started painting, and I sold a few paintings in several countries. Then during the Revolution, I went to the streets on the first day, and we did all that we could, but then I felt that I needed to express more, to do more. And the best way for me to express is through art.

What drove you to begin creating these sculptures?I used to work with the United Nations, then I quit my job to be an artist because I felt the need—it was not the want, but the need—to paint and to do art. So I quit my job around 2016 or 2017. I started painting, and I sold a few paintings in several countries. Then during the Revolution, I went to the streets on the first day, and we did all that we could, but then I felt that I needed to express more, to do more. And the best way for me to express is through art.

I saw some guys, some pro-government protesters, they came and they broke our tents—the protester’s tents—in Martyrs Square. And people had put the broken tents under the Fist of the Revolution. So I got the idea to create a phoenix out of the broken tents because I could not see broken things related to the Revolution. I did not want them to break us. And I wanted to fight back through art. And I hadn’t done any sculpture ever in my life before. I did not know how to do it, but I so wanted to do it.

(continued) Then, on the Day of Independence, I woke up and I saw that some pro-government people came and burnt the Fist of the Revolution because they want to end our revolution. So I said to myself, today the phoenix should be born and it will rise and I went to the street and when I went to Martyrs Square and I started removing the metal. Then people—because it was Independence Day and it was a day off—who had come from all over Lebanon to participate in an event to protest started asking me, why are you removing the metal? What are you going to do? I told them that I wanted to build a phoenix out of it because a phoenix is a bird that every time they burn it, it will rise again from its own ashes. Then suddenly, people started helping me build the Phoenix—old, young, children, women, men from all over Lebanon. All religions, sects, all areas, hand in hand, they were helping me without knowing each other’s names.

(continued) Then, on the Day of Independence, I woke up and I saw that some pro-government people came and burnt the Fist of the Revolution because they want to end our revolution. So I said to myself, today the phoenix should be born and it will rise and I went to the street and when I went to Martyrs Square and I started removing the metal. Then people—because it was Independence Day and it was a day off—who had come from all over Lebanon to participate in an event to protest started asking me, why are you removing the metal? What are you going to do? I told them that I wanted to build a phoenix out of it because a phoenix is a bird that every time they burn it, it will rise again from its own ashes. Then suddenly, people started helping me build the Phoenix—old, young, children, women, men from all over Lebanon. All religions, sects, all areas, hand in hand, they were helping me without knowing each other’s names.

We built the Phoenix together and it became a huge symbol of the Revolution. It got a lot of attention and media coverage and everyone was taking pictures next to it—even tourists came to Lebanon to participate in the Revolution and to take pictures of the Phoenix. But a few days ago, those pro-government people broke and burnt the Phoenix. They broke its wings and stole the head of the Phoenix, which broke my heart, actually. That was the first sculpture I’ve ever done. Lots of people cried while we were building it because it was very emotional and lots of people cried and called me when it got broken.

How did you go about gathering the material to create the port sculpture?The explosion happened and I stopped everything. I went to the streets and I started bringing mattresses, tents, food, everything that I could gather to help people who got affected by the explosion. And that’s what I did at the beginning. Then we started cleaning people’s houses and the streets so that people could go back to their homes because the houses were filled with shattered glass, broken furniture, and everything. So I asked for volunteers on my Instagram. Lots of people joined me and we went and cleaned houses, and I did not want to throw away the rubble. I packed it in bags, and I took it with me to my house which is also my workshop.

How did you go about gathering the material to create the port sculpture?The explosion happened and I stopped everything. I went to the streets and I started bringing mattresses, tents, food, everything that I could gather to help people who got affected by the explosion. And that’s what I did at the beginning. Then we started cleaning people’s houses and the streets so that people could go back to their homes because the houses were filled with shattered glass, broken furniture, and everything. So I asked for volunteers on my Instagram. Lots of people joined me and we went and cleaned houses, and I did not want to throw away the rubble. I packed it in bags, and I took it with me to my house which is also my workshop.

Can you describe some of the items that went into making her?I had started a sculpture of a woman before the explosion. I did not know why I was doing it. But I was. Sometimes I don’t know why I do projects. And then, after I do them, I discover why I’m doing them. And, you know, Beirut has been destroyed so many times. It’s not the first time so I felt that the struggle should be part of the creation of the sculpture of the woman and I felt that Beirut is a woman. And to so many people, Beirut is a woman, and she’s a beautiful woman.

Can you describe some of the items that went into making her?I had started a sculpture of a woman before the explosion. I did not know why I was doing it. But I was. Sometimes I don’t know why I do projects. And then, after I do them, I discover why I’m doing them. And, you know, Beirut has been destroyed so many times. It’s not the first time so I felt that the struggle should be part of the creation of the sculpture of the woman and I felt that Beirut is a woman. And to so many people, Beirut is a woman, and she’s a beautiful woman.

So I started creating the sculpture made out of the rubble. I wanted her to look beautiful because Beirut is beautiful, but she had to show the pain of those who died and of those who got injured. There was a thin line between making her look beautiful because Beirut is beautiful. Beirut is so beautiful, that everyone wants a piece of Beirut. And that’s what happens when a woman is so beautiful and everyone wants her and it hurts her sometimes and that’s what happened to Beirut. If you see her face, it’s injured; her legs are made out of broken glass, her dress is made out of broken metal and copper that I also found. It’s all upcycled. There are also broken mirrors that reflect the light.

Can you describe the sculpture in your own words and your thought process in the composition?

Can you describe the sculpture in your own words and your thought process in the composition?

I kept one hand down. She’s too tired, this hand is too tired to even be lifted. And her legs are just standing still as if she doesn’t want to move. The hair looks as if it’s still flowing in the air. And, you know, when the explosion happened there was a lot of force and pressure from the air. So I wanted her hair to feel as if the explosion is still happening. Underneath all of that on the right, there’s the broken clock that I found in the streets and it had stopped at 6:08 or 6:07, which was the time of the explosion.

I included it in the sculpture because so many of us feel like we cannot move on. We are still stuck in time at the time of the explosion, we are not over it, we are still traumatized. And this part expresses the pain that we are going through and the trauma that we are going through. On the left, you see the hand is lifted because she wants to rise, she wants to continue to rise again, she wants strength. Also the leg on the left. If you see it, it’s a bit bent as if she’s just about to walk—she just was about to move to rise. And this is what I wanted to show. It’s reality. We want to rise, but we are in pain.

At first, I made her carry a broken mirror in the shape of a V because I wanted people to see themselves in the reflection. But unfortunately, while moving the statue to the port, the mirror in her hand broke. On October 17 people were carrying torches from all over Lebanon to light a big torch and so I also made her carry one. So first there was a broken mirror and then she was carrying a torch and then I had to remove the torch from her hand on the day of the first anniversary of the Revolution. During that event, I took the torch, which represented the torch carried by people from all over Lebanon, from her hand and used it to light a huge torch which is also at the port.

She was lighting the torch of the Revolution. When I removed the torch, her hand was empty. Someone came and asked me if he could put the Lebanese flag in her hand, and so we made her carry the Lebanese flag. The next day, because of the wind, the flag flew away. So she was left with the wooden stick and looks like she is carrying a sword. So in some pictures, you see her carrying a sword, in some pictures a torch, in some a flag, and some just a mirror. I love that it’s interactive.

What was the reaction of people to the artwork?

What was the reaction of people to the artwork?

So many people have contacted me—those who lost people in the explosion, the families who lost their mothers or their children, some who have the same injury on their faces, they contacted me and they told me they cried. When they saw this sculpture, they told me that they were not able to express how they feel on the inside. Sometimes words cannot express a feeling that is so deep and enormous on the inside and they told me that this sculpture represents exactly how they feel. It was very emotional for them.

Because the Phoenix was burned, you’ve decided to move this sculpture to protect it. Can you talk a bit about that?

Because the Phoenix was burned, you’ve decided to move this sculpture to protect it. Can you talk a bit about that?

A few days ago, some people came and burned and broke the Phoenix. People were very worried that someone would break her, because she now represents the people and their pain and their dreams and everything. So I had to remove her from the port. But my plan, and what people actually want, is to create a replica of her—a huge one. This one is a little less than three meters tall. What we wish to do is to create a huge replica that would last, that would serve as a memorial for everyone who died and for everyone who got injured—physically and emotionally and psychologically. And for that, I need to raise funds to create a long-lasting sculpture that represents the first biggest explosion—nonnuclear explosion—in the world, and the third biggest in the world.

What do you hope that people in Lebanon and beyond take away from your work?

What do you hope that people in Lebanon and beyond take away from your work?

I am an artist and even I did not know the effect and the importance of art before the Revolution. I loved art, but I used to feel that I cannot make a change through art and I’m someone who believes that we have a life purpose and we need to make a change in this world. I’m driven by positive change and I felt that through art I was not going to be able to do that. But during this Revolution, it actually changed my life.

So when I started, many people questioned me. They said, it’s just art, let’s go and do better things like blocking the roads and all of that. Some people—very few—were like, oh, it means nothing. You know, it’s just art. How is it going to make a change? But then they saw international media filming and they saw how we were able to deliver our message all over the world through art. They were like, okay, you were right about doing the sculpture. And then, when the government sent people to remove all the tents from Martyrs Square because of COVID-19, the only thing that stayed was the artwork. And these same people, they called me and told me they were wrong. It’s the only thing that stays, that is still shouting revolution.

And some of the protesters who never even knew anything about art or who did not care about art, they were the ones who helped me build it, who kept on protecting the Phoenix. I received calls from people who never cared about art, they were like, let’s build it again, we can not let them break us. We are ready, whenever you want. They are the ones who take pictures. And they send me pictures of themselves cleaning around the Phoenix, although it’s broken, but they are cleaning and trying to fix it. These are the people who never knew anything about art or industry. Now, through art, they were touched.

Hayat Nazer: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Hayat Nazer.

In Europe and the US, abortion rights are under renewed threat

November 1, 2020

(CNN)The Abortion Dream Team usually receives about 400 calls a month, from women seeking advice and information. Last week, the Polish advocacy group had 700 in the space of three days, according to team member Justyna Wydrzynska.

‘A time for deep concern’

Restrictions across Europe

In the past decade, several countries including Armenia, Russia, and Georgia introduced preconditions that women must fulfill before they can obtain abortion services.

In other countries attempts to roll back abortion rights have been largely unsuccessful, often following a public outcry and large-scale demonstrations, but “they provide a powerful illustration of the extent and nature of the backlash to the advancement of women’s rights and gender equality in some parts of Europe,” according to a 2017 paper published by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights.

Global attitudes about abortions

What If Women’s Suffrage Never Happened?

There’s a tendency, when looking back on the history of women’s suffrage in the United States, to assume that it was inevitable that women would get the right to vote: By the time Tennessee became the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment, on August 18, 1920, 15 states had already granted women suffrage, starting with Wyoming, which became a state in 1890. (As a territory, it gave women suffrage in 1869.) How long could such an electoral-rights imbalance reasonably be expected to survive?

Then again, was it really inevitable? The amendment’s passage was the culmination of probably the longest sustained sociopolitical movement in American history, and even so it came down to a single 24-year-old Tennessee state legislator’s vote—changed from nay to aye after his mother wrote him a letter lobbying him to do so—or it wouldn’t have happened, at least not in 1920. And even then, the 19th Amendment hardly put an end to systematic disenfranchisement (and not only of women) in this country. On a practical basis, Black women in the South, and to some extent Black women anywhere, still didn’t get to exercise their right to vote (as Black men hadn’t and didn’t)—not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 swept away many of the tactics vote suppressors had used for decades to thwart them. Native American women (along with Native American men) didn’t get the vote until 1924, when their citizenship was recognized (they weren’t guaranteed the right to vote in every state until 1962); all Asian-American citizens didn’t get the vote until 1952, when the McCarran-Walter Act granted all people of Asian ancestry the right to become citizens. As an additional point of comparison, women in Switzerland were not granted the right to cast a ballot in their national elections until 1971. Imagine how different this country might be—socially, culturally, politically—if women had been forced to wait 51 more years before successfully seizing the right to exercise their power at the polls. Imagine how different things might be if women never got that right.

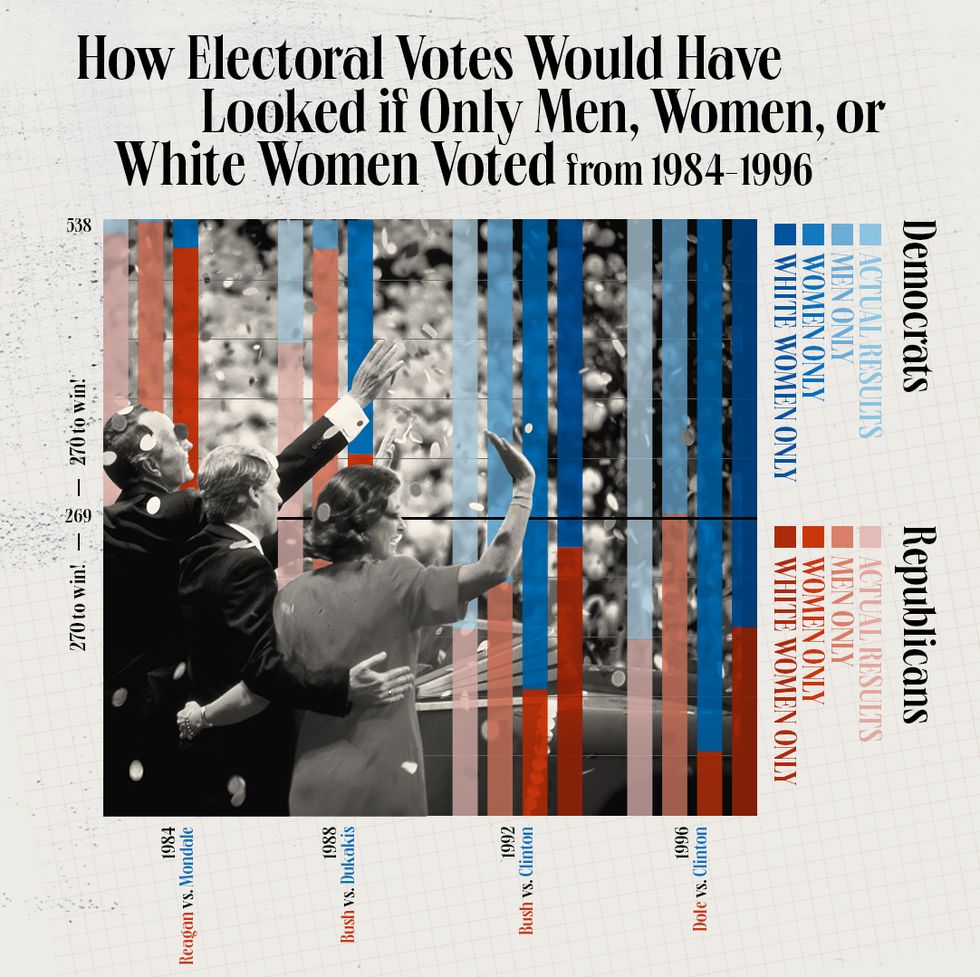

The contemplation of hypothetical, alternative histories—the conjuring of counterfactual scenarios and the spinning of stories about what the world and our lives might be like if this, this, or this had happened or not—is an endlessly fascinating pastime. (The “What if the Nazis had won?” alternative-history subgenre has lately seen a particularly strong resurgence with the bingeworthy Hollywood adaptations of The Man in the High Castle and The Plot Against America.) It’s also a deeply fraught exercise, with each counterfactual pivot triggering an endless range of possible implications and outcomes, each of which in turn sets in motion its own innumerable ripples of “what if.” We can’t say definitively how a century of women voting has shaped the world we live in or what that world would look like in its absence. But we can crunch some numbers and offer some data-driven possibilities. We can, for instance, examine state-by-state exit polling from presidential elections to see whether and how the Electoral College might have swung if men alone had wielded the ballot.

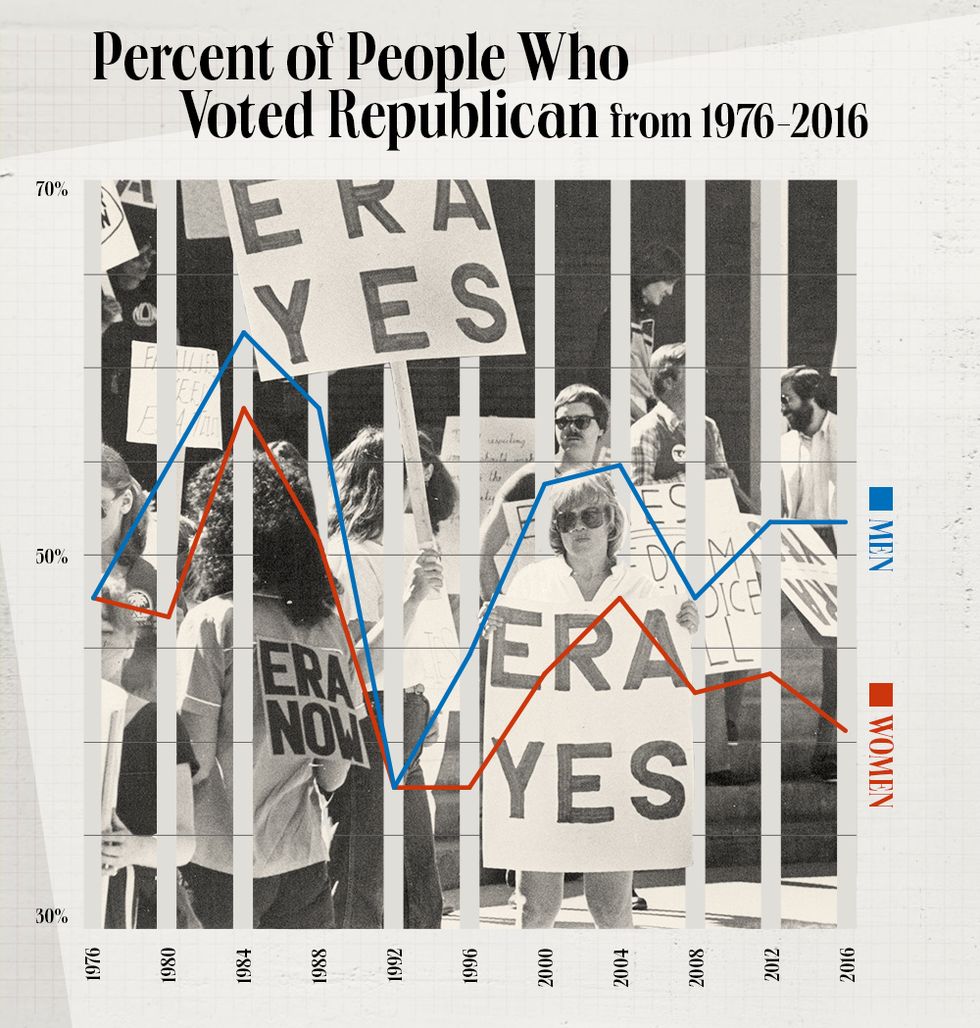

And when we do so, here is what we find: Women’s and men’s votes have been diverging in significant ways for several decades, so much so that at least two relatively recent elections might very well have gone the other way—from the Democratic candidate to the Republican—if women had still been barred from the polls on election day.

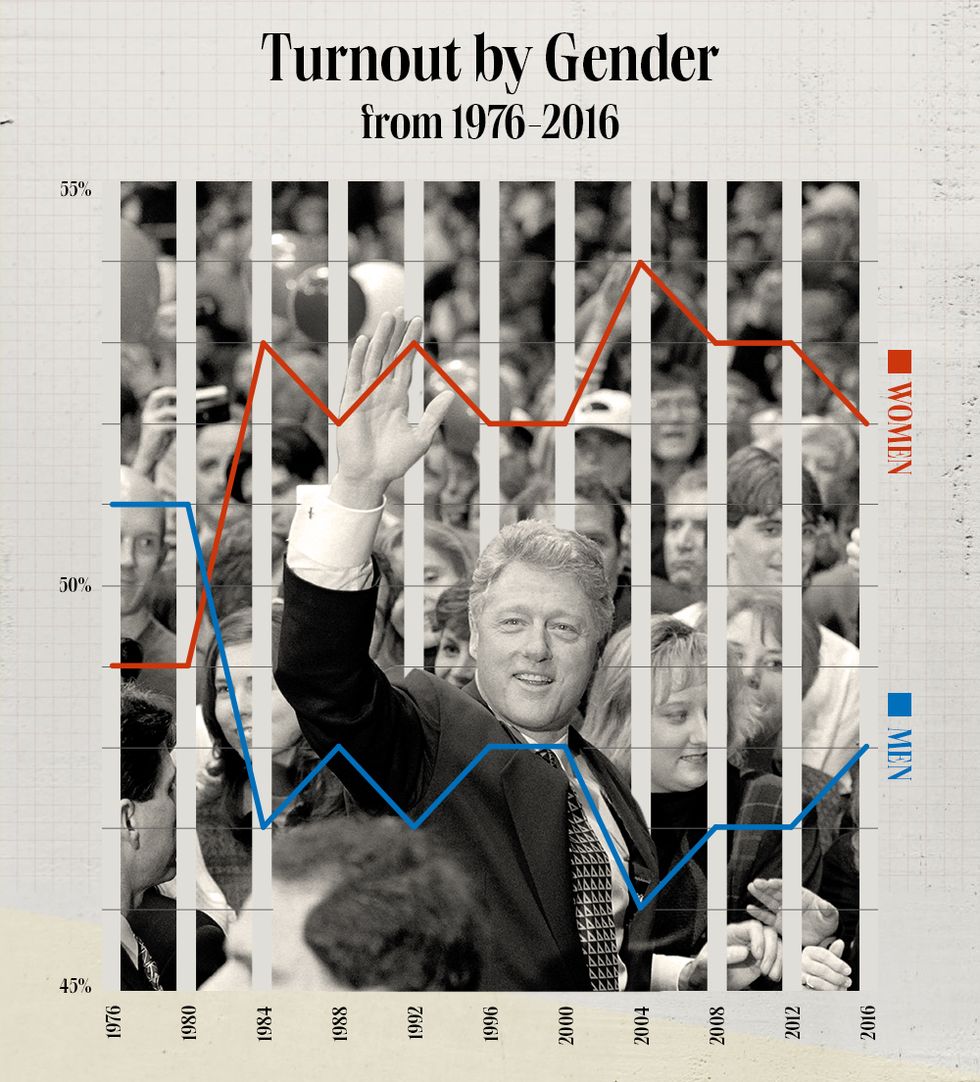

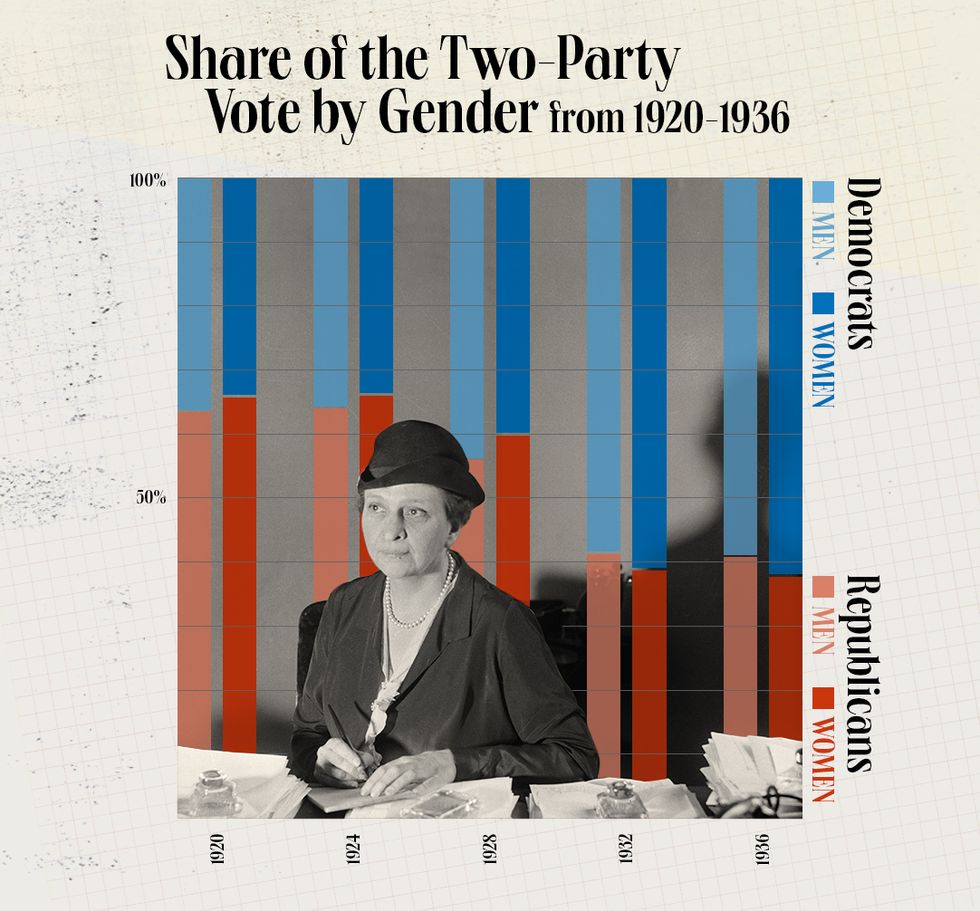

For a while after the 19th Amendment went into effect, it looked as if the entry of women into the electorate would have little or no tangible impact at all. Women didn’t vote at nearly the level men did—36 percent of eligible women cast a ballot in 1920, versus 68 percent of men—and when they did vote, they tended to do so pretty much as men did. “Suffragists get a bad rap because the amendment passes, and then the world doesn’t change,” says Susan Ware, author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. “It wasn’t as if all of a sudden women threw all the politicians out of office and decided to end war and end prostitution and all these things. But suffragists never claimed that the world would change. They didn’t say women would vote as a bloc and war would end.”

In some ways, the specter of a woman’s vote seems almost to have had more power than the vote itself—at first. “Right after 1920, we get the Sheppard-Towner Act, which provides support for mothers and infant care,” says Christina Wolbrecht, director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the University of Notre Dame and co-author of A Century of Votes for Women: American Elections Since Suffrage (which is where the 1920 voter-turnout stats above come from). “We also get the Cable Act, which says that if you’re a woman and you marry a foreigner, you don’t immediately lose your American citizenship. And then it turned out that women didn’t vote that differently than men and most of them stayed home, so politicians decided that they weren’t really a threat anymore, and so we don’t really need to pay as much attention to their agenda items. So you don’t see as much of those issues in the ’30s and into the ’40s.”

But what you do see in the ’30s and ’40s is women deploying a political savvy honed during the long campaign for suffrage, gathering and exercising a type of soft power to mold policy and shape national agendas from positions just out of the spotlight. “When we think about the impact of women’s suffrage,” Wolbrecht says, “an obvious focus is outcomes of elections. But we also might ask about something we would call in political science the second face of power. One face of power is, something is being debated and you can determine the winner or the loser. The second face of power is just getting that thing to be talked about in public life, to be on the political agenda. And by becoming voters, women had more power to influence the political agenda.”

Ware offers the Social Security Act as an example of this sort of exercise of soft power. “The secretary of labor at the time that was passed was Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in the cabinet,” she says. “And Frances Perkins was a former suffragist.” (In fact, so pervasive was Perkins’s influence on the blossoming of social programs during the FDR administration that Collier’s magazine would later describe those accomplishments as “not so much the Roosevelt New Deal as…the Perkins New Deal.”)

But for the most part, if your hopes as a suffragist, or your aims as a counterfactualist, are to find in the early decades of women’s voting evidence that the ballot was a power wielded by women to bring about sociopolitical change, you are doomed to disappointment. “In eras where there’s a lot of traditional ‘family values’ conservatism, where men are the primary breadwinners, stay-at-home women will support the conservative party very strongly,” says Kevin Corder, a professor of political science at Western Michigan University and co-author with Wolbrecht of A Century of Votes for Women. “In countries where they introduced suffrage at a time when you had a lot of traditional values, women were overwhelmingly voting for the conservative party. And that’s what the U.S. electorate in the ’50s did.”

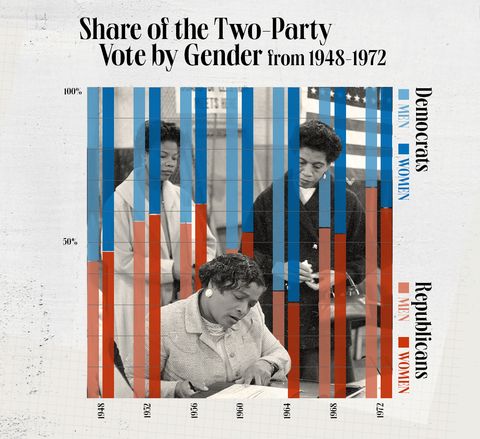

In fact, to the extent that there was a partisan gender gap—a measurable difference between women’s and men’s relative support for the same candidate—throughout the 1950s and into the early ’60s, it showed a tendency for a slightly higher proportion of women than men to vote Republican. That changed by 1964, with both women and men favoring Lyndon Johnson in his trouncing of Barry Goldwater and women favoring the Democrat to a slightly greater degree, a pivot that heralded what became a slowly growing schism between the sexes, driven by some combination of men migrating rightward and women leftward.

“The 1960s is also when the parties become sharply defined on social welfare,” Wolbrecht says. “One party says government is the problem; the other says government is the solution. If you’re economically vulnerable, the party that wants to have a social safety net may be more attractive to you. But even for women who are not economically vulnerable, something like 60 to 70 percent of the growth in middle-class women’s employment comes from the public sector. They are the public schoolteachers for the baby-boom kids. They’re the nurses in public hospitals. They are the social workers in all of these Great Society programs. They’re all these sorts of things that make their own economic interests much more linked to an active federal government.”

There is an insistent article of faith among scholars of women’s suffrage that goes like this: “Women” is not a voting bloc. “The category of ‘women,’ when it comes to voting, is just too broad,” Ware says. “I’ll give you two examples. One is the suffrage movement itself, where you had women who were for the vote and a lot who were against it. And the Equal Rights Amendment, where you had a lot of feminists struggling for the ERA and then you had antifeminists who were vehemently opposed to it. You have to be very, very careful about talking about women as a group and any expectation that there would be a women’s bloc; it just doesn’t hold up.” And with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 opening the electorate up to far greater numbers of Black women, it would soon become clear just how absurd it is to think that women all vote the same.

Ronald Reagan’s 489–49 electoral-vote shellacking of Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election was fueled, not surprisingly, by support from both men and women. What was surprising, or at least notable, was the difference in the scope of support for Reagan between the sexes. Reagan outpolled Carter among men by a whopping 55–38 margin (Independent candidate John Anderson took 7 percent of the votes); among women, Reagan barely squeaked out a 47–46 victory. Feminists seized on the eight-point (55 versus 47 percent) “gender gap” in votes for Reagan (Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women at the time, is generally credited with coining the term) as a way to highlight the importance of the women’s vote and of promoting policies that women care about. (This came at a time when the parties were becoming distinctly polarized around some of those issues; Republicans removed support for the Equal Rights Amendment from their party platform in 1980 for the first time in 40 years.)

The gender gap waxed and waned, though mostly waned, until 1996, when Bill Clinton ran for his second term, against Bob Dole, and the gap ballooned to 11 percent. The interesting thing about this particular shift is what it reveals about the dynamics that underpin it. In the previous election, the gap had been only 4 points, with both women and men favoring Clinton over George H.W. Bush—women giving Clinton 45 percent of their vote and men 41. (The numbers are skewed by the fact that H. Ross Perot performed so well as a third-party candidate, taking 21 percent of men’s votes and 17 percent of women’s.) “What happens in 1996,” Wolbrecht says, “is that women become more Democratic, but it’s also that many men returned to the Republican Party.” This is an important point: The gender gap is not just about how women vote. As Wolbrecht puts it, “1996 is such a great example of how the gender gap can be driven by both men and women.”

And those antipodal shifts by men, in turn, lead us to the first of our “What if women never got the right to vote?” electoral overturns: A close examination of state-by-state exit-poll numbers indicates that if women hadn’t voted in 1996, Bob Dole would have flipped the results in nine states and won a narrow victory, depriving Clinton of a second term. Here are a few other things that an all-male electorate would have deprived Clinton of: credit for four straight years of budget surpluses and the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in U.S. history; a successfully negotiated end to the war in Kosovo; and making Madeline Albright the first female secretary of state. Dole would have enjoyed Republican control of both houses of Congress, giving him the opportunity, perhaps, to achieve more in his first term than Clinton was able to in his second, so maybe he would have managed to abolish the four cabinet departments (Housing and Urban Development, Energy, Commerce, and Education) he had in his sights or to sign a bill (like the one Clinton vetoed toward the end of his first term) to allow drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. One distraction he (and the country) likely would not have faced: the impeachment of a sitting president. Monica Lewinsky would probably not have become the household name she did. And who knows what impact all that might have had on Hillary Clinton’s political career.

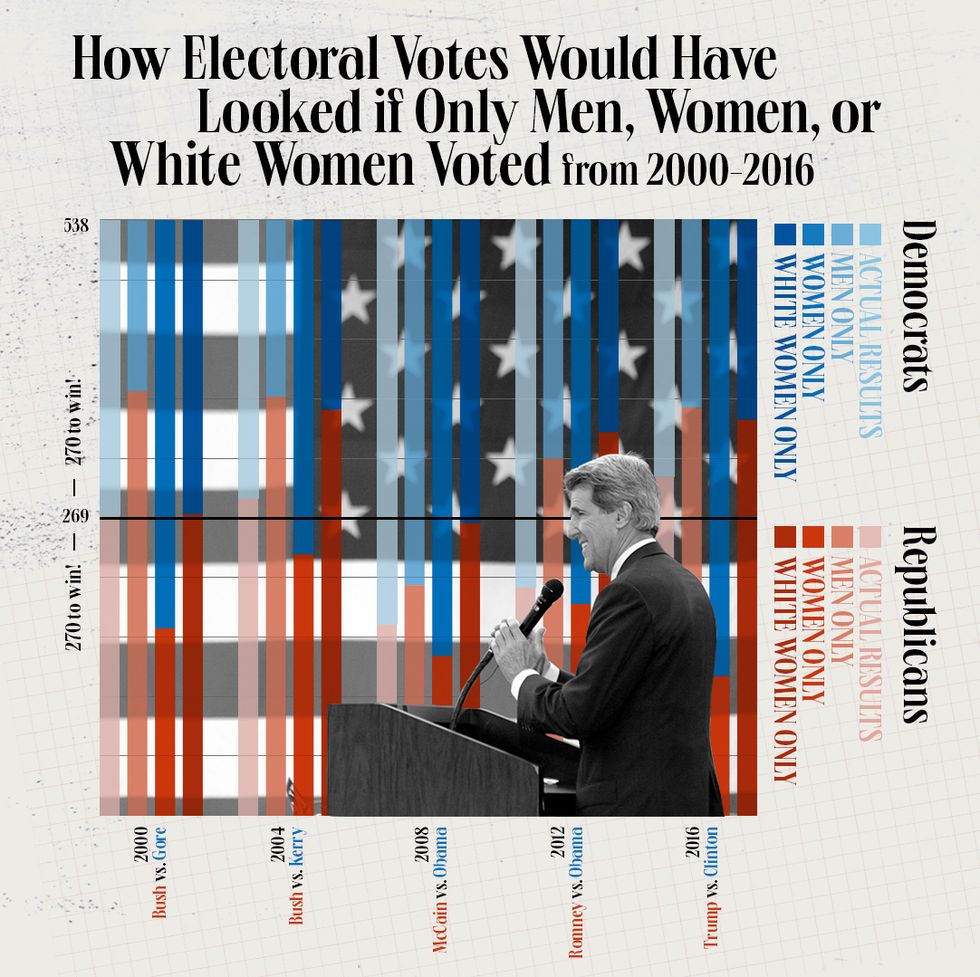

Of course, if that’s the way history had actually gone, all bets would be off for how subsequent elections would have unfolded—since two Dole terms means no George W. Bush hanging-chad victory in 2000, and on and on. So let’s file Dole’s 1996 triumph away in the annals of alternative history and travel ahead another 16 years to take a look at the second upset the all-male electorate would have bestowed. This one, again, is the denial of a second term to a Democratic president, with Mitt Romney snatching nine additional states away from Barack Obama in 2012 and scoring a 322–216 Electoral College win. Here are a few things that happened in Obama’s second term that might thus have vanished into the alternative-history mists: the Iran Nuclear Deal, the Clean Power Plan, the Paris climate accord. One other thing that almost certainly would have gone away if Romney had run in 2016 for his second term: the presidency of Donald Trump. (Didn’t we warn you this was a fraught exercise?)

To illuminate the influence of women’s votes on presidential elections from a different angle, we also crunched the numbers on the opposite postulate: What if only women had the right to vote? A few highlights: Bill Clinton beats George H.W. Bush by a lot more in 1992 and absolutely demolishes Bob Dole in ’96; Al Gore wins with a comfortable 368 electoral votes (and no need for a Supreme Court intercession) in 2000; John Kerry claims a victory in 2004; Obama cruises to two terms; and Hillary Clinton actually does become the first woman president in U.S. history, beating Donald Trump 412–126 and presumably presiding this year over many joyous celebrations of the centennial of women’s suffrage.

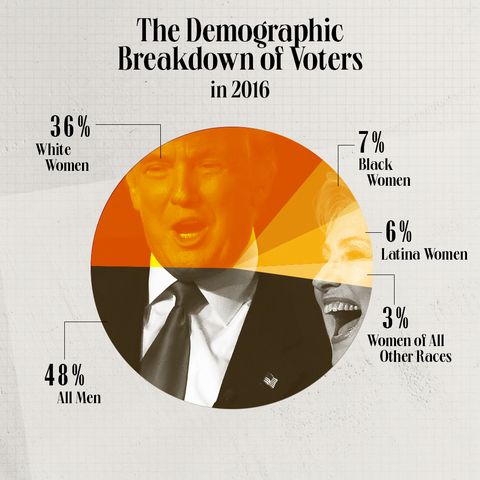

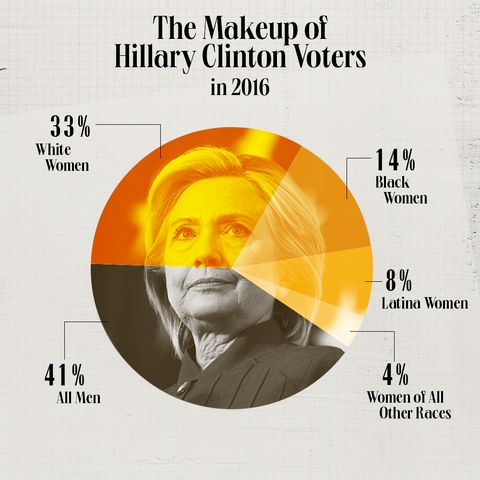

If that litany of outcomes reinforces your belief that women have become a staunchly reliable source of Democratic votes…then you haven’t been paying close enough attention. Remember “‘Women’ is not a voting bloc”? Because a deeper crunch of the exit-poll data reveals just how consequential the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act truly was on the electoral calculus: It’s not “women” who, if they were the only ones with the vote, would have been responsible for sweeping an unbroken string of Democratic candidates into office over the past three decades; it’s Black women and, to a slightly lesser extent, other women of color. If the power to vote had been held by white women only, every presidential election over those 32 years would have had the same outcome, with one exception: Romney would have beaten Obama in 2012 (and by a bigger margin than if only men had voted in that election).

Trump would have won in 2016 by 51 more electoral votes than he did. It’s only the overwhelmingly Democratic votes of non-white women that push the overall category of “women voters” resolutely into the Democratic column. As University of Michigan political scientist Ken Kollman pithily sums up: “Trump won the majority of white women. He got slaughtered among Black women and Latina women.”

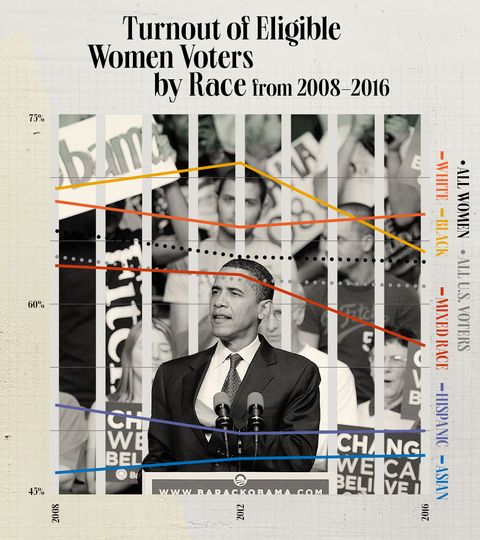

Above: In 2016, nonwhite women made up 16 percent of all voters yet contributed to 26 percent of Clinton’s total votes. If just white women had voted, Trump would have won by an additional 51 electoral votes.

Kollman is far from alone among electoral scholars in anticipating the possibility that the 2020 election might emerge as a gender-gap pivot point—and a harbinger of challenging times to come for the Republican Party. “The data show that Trump is uniquely disliked by women,” he says. “And a lot of that is driven by women under 45. The partisan gap between men and women is increasing in the population as a whole, but it’s really a big step by generation. You go down in age and the gap gets bigger and bigger and bigger. And the modern Republican Party is in trouble. It’s not just that young people are being driven away from the Republican Party, which is true, but that young women are being dramatically driven away from the Republican Party.”

Heading into this centennial year for women’s suffrage, Susan Ware would find herself trying to conjure in her imagination a society where women can’t vote. “I went to my first feminist demonstration in 1970, on the 50th anniversary of women voting,” she says. “That’s not that long ago! I was born in 1950, and women had been voting for only 30 years, and that seems really bizarre to me. I haven’t found a really good way of conveying this to people, but just try to imagine a landscape where half the population is arbitrarily denied the right to vote because of their sex. To me, that’s the importance of suffrage: that we got past that hurdle.”

Ware, who has spent much of her career writing about the early suffragists, also likes to torture herself by trying to imagine what her biographical subjects would make of how far—or not—the country has come since 1920: “If I could bring my women up to the present and say, ‘All right, here’s where we are 100 years later,’ what would they think? Would they say, ‘Way to go, this is much further than we expected!’ or would they say, ‘Come on, Susan, not enough has happened.’ I go back and forth.”

One thing she does know, though, is that the right to vote, and to have a voice, is not something to be won and then taken for granted. “The suffragists needed to get women the vote, and it was a hard and a long struggle, and then it’s been up to women in the years since to figure out what they want to do with it,” Ware says. “And that process is still ongoing. And it will be going on long after I’m not here. But I see myself as being part of something bigger. And I see the centennial as being part of something bigger. I would hope that maybe you will get your readers thinking about that. And then the last line of your story has to be to remind them to vote no matter what.”

Oxford dictionaries change ‘sexist’ and outdated definitions of the word ‘woman’

From CNN/By Christina Zdanowicz/ November 9, 2020

https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/09/world/woman-definition-revised-oxford-dictionary-trnd/index.html

The word ‘woman’ is being redefined in one series of dictionaries.

The word ‘woman’ is being redefined in one series of dictionaries.(CNN)Even the dictionary can be sexist and out of date, especially when it comes to how a “woman” is described.

Through the Window

The first photograph taken by NIEPCE around 1826-1827. View from the place where he took it.

The first photograph taken by NIEPCE around 1826-1827. View from the place where he took it.

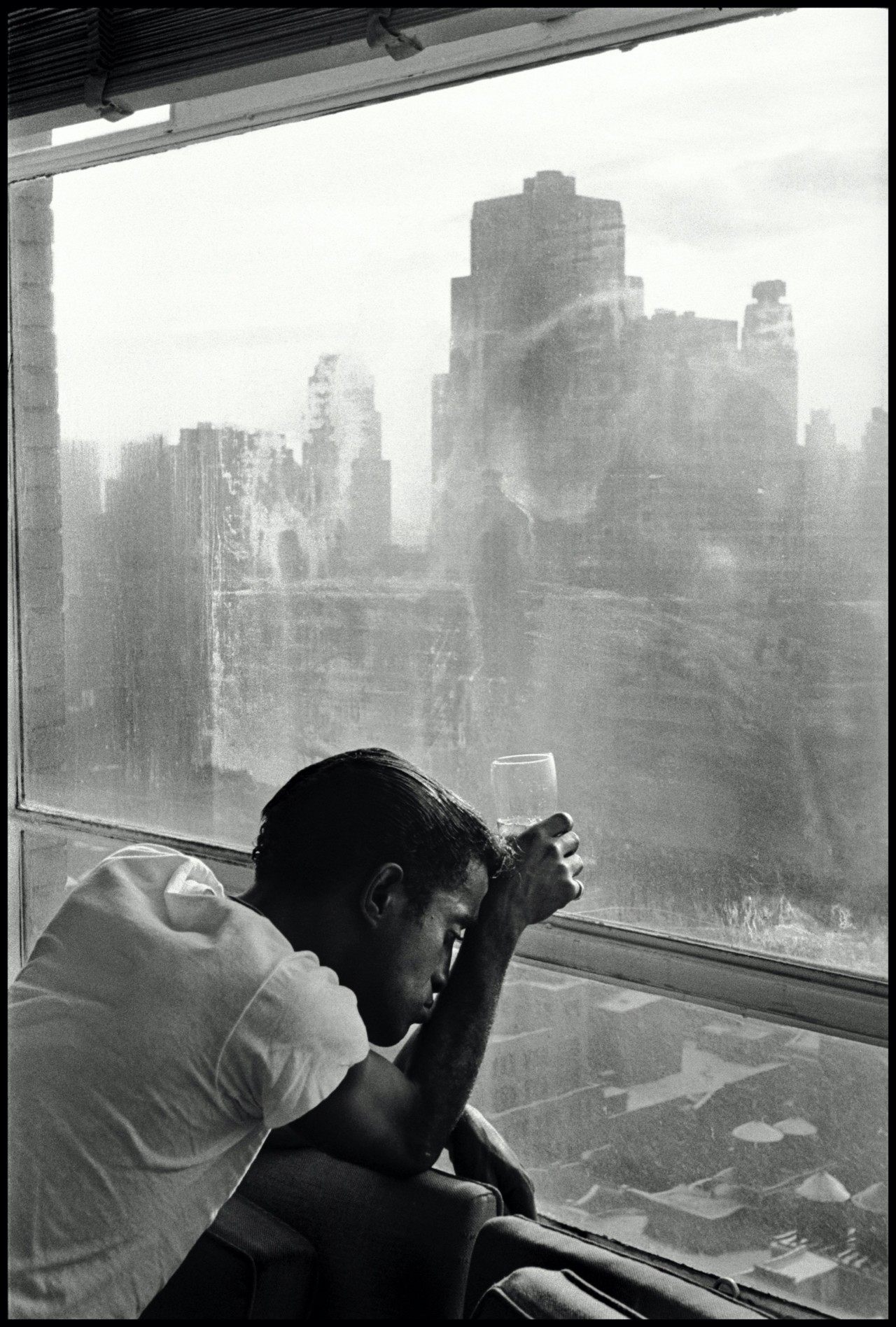

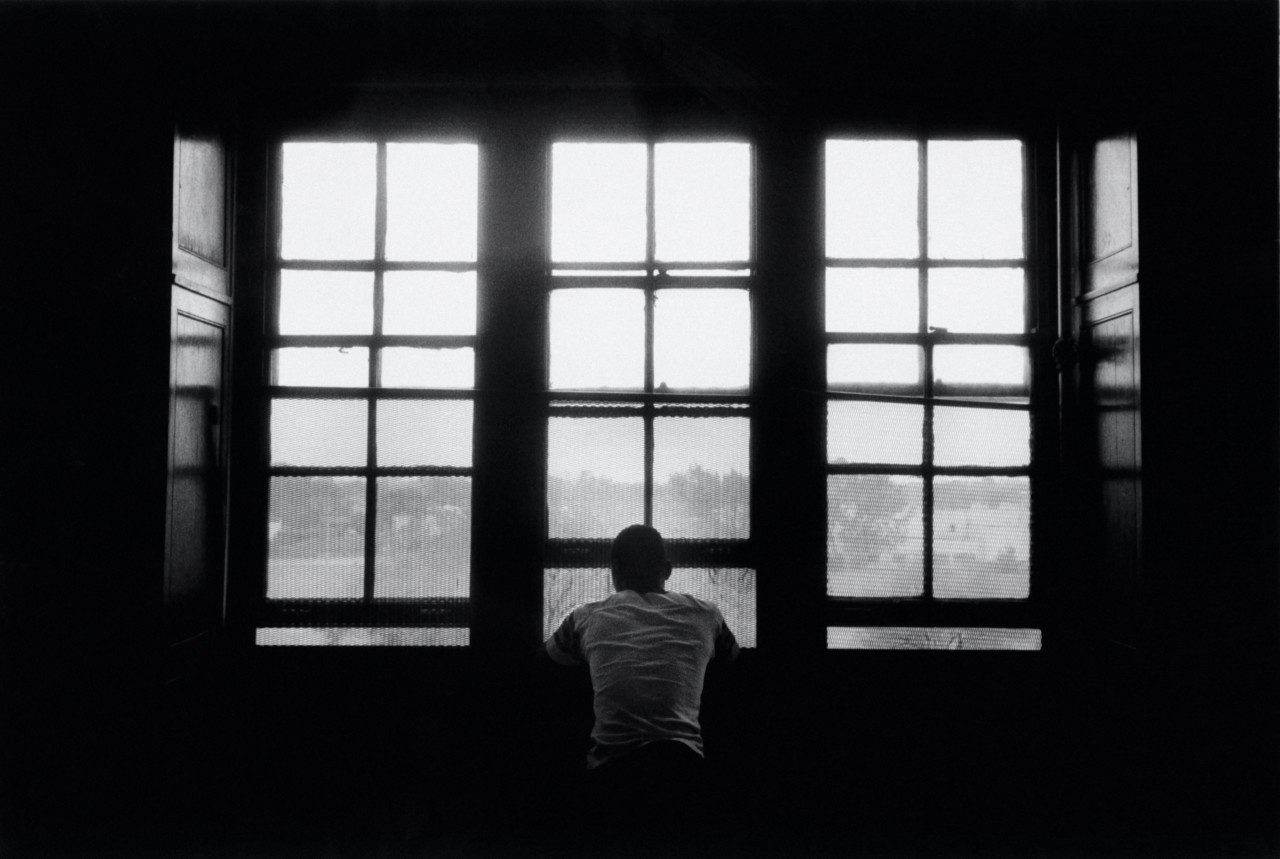

USA. New York City. 1959. Sammy DAVIS Jr. looks out a Manhattan window.

USA. New York City. 1959. Sammy DAVIS Jr. looks out a Manhattan window.

The Midlands, 1964.

The Midlands, 1964.

New housing development.

CANADA. Lambton County, Ontario. 1974.

CANADA. Lambton County, Ontario. 1974.

USA. New York City. 1976. Windows on the World owner Joe Baum, silhouetted against view from the restaurant.

USA. New York City. 1976. Windows on the World owner Joe Baum, silhouetted against view from the restaurant.

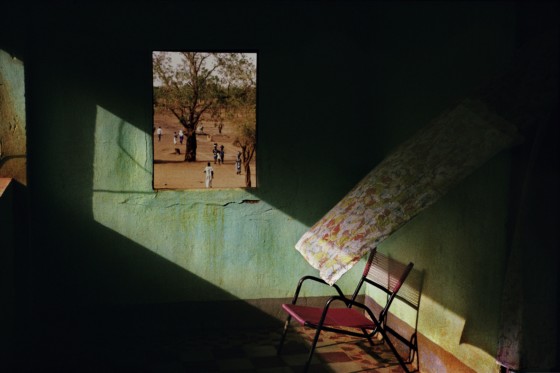

Mali. Town of Gao. 1988.

Mali. Town of Gao. 1988.

Terrace of a local hotel.

USA. Detroit, Michigan. 1988. A state school for orphans.

USA. Detroit, Michigan. 1988. A state school for orphans.

GB. England. ‘I don’t think it’s anything particularly forced on Deborah. We’ve just always enjoyed the same sort of things.’ From ‘Signs of the Times’. 1991.

GB. England. ‘I don’t think it’s anything particularly forced on Deborah. We’ve just always enjoyed the same sort of things.’ From ‘Signs of the Times’. 1991.

USA. Brooklyn, NY. 2009. Marion on bed.

USA. Brooklyn, NY. 2009. Marion on bed.

USA. NYC. 2016. Tatyana Enkin and Warren Estis at their home on the 86th floor of the Trump Tower at United Nations Plaza

USA. NYC. 2016. Tatyana Enkin and Warren Estis at their home on the 86th floor of the Trump Tower at United Nations Plaza

USA. NYC. June 21st, 2017.

USA. NYC. June 21st, 2017.

FRANCE. Paris. 2019. DAU cinematic project.

FRANCE. Paris. 2019. DAU cinematic project.

The US is officially out of the Paris Climate Agreement. Here’s what could happen next

From CNN/By Drew Kann/November 4, 2020

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/11/04/politics/us-exits-paris-climate-agreement-next-steps/index.html

(CNN)The US became the first country to officially exit the Paris climate accord Wednesday, the landmark agreement aimed at protecting the planet from the worsening impacts of the climate crisis.

Biden intends to rejoin if he wins

Top emitters besides the US remain signed up

Young YouTube influencers are increasingly marketing junk food to fellow kid

From CNN/ By Ryan Prior

https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/26/health/youtube-influencers-junk-food-wellness/index.html

(CNN)Kid influencers on YouTube are marketing junk food and sugary beverages to their fellow kids, and they’re racking up billions of page views, according to a new study published Monday in the journal Pediatrics.

A new kind of marketing

A new law to protect children

Captivating case files of the wedding photo detective

Captivating case files of the wedding photo detective

- Charlotte Sibtain, 33, has more than 400 snapshots of strangers’ weddings

- She has collected them from antique shops, car boot sales and markets

- Her work has uncovered stories ranging from lifelong friendship to infidelity and even murder

Like many former brides, Charlotte Sibtain has a number of beautiful wedding photographs dotted around her London home.

Black and white, and in all shapes and sizes, they compose a striking montage of a day which, traditionally, is the happiest of a couple’s life.

Charlotte, 33, has been married for four years but none of these photographs is of her own nuptials.

Instead, they are snapshots of strangers’ weddings — more than 400 in total — which she has lovingly collected from antique shops, car boot sales and markets over the years.

Sonya Diana Fleur Paynter on her wedding day, at St Peter’s Eaton Square on December 1959. Pictured with stepfather Paull Hill

But Charlotte does not see them as people she has never met. ‘I may not know them, but to me they’re still special,’ she says.

‘They’ve got married, they’ve got dressed up. Then these pictures have been tossed away and discarded.

‘So I try to rescue them, look after them and then, in an ideal world, give them back to their families.’

Charlotte’s hobby has led to her being dubbed ‘the wedding detective’.

No wonder, considering her painstaking sleuthing has resulted in many a discarded album being re-united with delighted relatives.

Her work has uncovered some heart-warming — and in some cases eye-popping — stories, ranging from lifelong friendship to infidelity and even murder and led to her becoming the subject of a three-part series on Radio 4.

‘What I love about wedding photographs and albums is that behind these individuals from decades ago are people we can all identify with — the slightly odd uncle, the grumpy bridesmaid, the over-enthusiastic mother of the bride,’ Charlotte says.

‘I also like the fact that when you look at the photographs you can tell what has been going on during that period — in wartime you can see evidence of rationing and the dress fabric is more make-do.’

Brought up in Brighton alongside her older sister, Charlotte has always had a lifelong love of history courtesy of her parents, who worked in education and were avid antique collectors.

She was raised in a house she describes as ‘stuffed to the rafters’ with everything from ancient ice skates to old cameras and sewing machines, and spent many happy hours as a child at antique markets and car boot sales — a hobby she carried into adulthood.

Charlotte Sibtain has a number of beautiful wedding photographs dotted around her home

Her unusual collection was kick-started 15 years ago, when, then aged 18, Charlotte found a small stack of black-and-white wedding photographs nestled between some 1970s postcards in a dusty corner of an antique market in her home town.

‘They were simple examples of 1940s and 1950s weddings and very typical of the time — you could even say they were unremarkable,’ she says.

‘But to me, it felt each one was unique and special: the dresses, the flowers, the venues, the guests. Each picture told its own personal story.’

Moreover, coming from a family where photos are treasured and kept in ‘countless’ albums, she was saddened by the way these pictures had been cast adrift.

‘I thought it was such a shame that they’d ended up discarded in their box somewhere, unappreciated and not looked at,’ she recalled.

‘So I bought three and framed them and put them up on my wall.’

Little did she know it would be the start of a longstanding passion: Charlotte now has hundreds of vintage photographs and wedding albums in her South-East London home, hunted down from charity shops and flea markets to car boot sales.

Ranging from the 1920s to the 1960s, all human life is here, from the four large prints of a wealthy family wedding in the ‘Roaring Twenties’ — all velvet and fur and spats on the groom’s shoes — to a snapshot from a working-class wedding dated 1910 which features the family on dining-room chairs placed on a rug in the middle of the street.

Her detective work began when she realised that one of her albums, from the 1950s, had the names of the bride and groom inscribed at the front — inspiring Charlotte to track down their descendants in North London and hand it over.

‘They were stunned at first because they hadn’t seen it for more than 20 years and had no idea how it got lost, but they were so thrilled to see it,’ she recalls.

‘It made me think this could be a thing I could do more often. But it’s hard as often there is so little information.’

It’s certainly no easy task: often armed with little other than a hastily scribbled date or location of the wedding on the back of a photograph which has come loose from an album — or sometimes just the name of the bride or groom — Charlotte has frequently had to piece together tiny fragments of information and use her instinct.

Since that first reunion she has tracked more families, using local libraries, censuses and newspaper archives, each one with their own compelling story — although arguably none more gripping than that behind the two photographs she pulled at random from a pile earlier this year and which featured in the first episode of the three-part Radio 4 series.

Marked with the name of a local press agency, one featured the name of the wedding venue, St Peter’s Church in London’s Belgravia, while the other was inscribed on the back with the words ‘Paull’ — spelt with a distinctive two ‘ls’ — and Sonya, the ‘impossibly glamorous’ bride.

Sonya Diana Fleur Paynter on her wedding day to Timothy (Tim) on December 1959

The photographs reeked of Hollywood glamour, and turned out to be suitably high society, the December 1959 wedding of Timothy and Sonya Bryant.

Little could Charlotte have known that from this she would uncover a trail that took her to West Cornwall and an extraordinary story involving Einstein, Marconi, landed gentry in decline, infidelity and a trial for murder.

Sonya was the granddaughter of Colonel and Ethel Paynter, who owned Boskenna House in West Cornwall, a mansion and 2,000-acre estate that became a magnet for the rich and famous in the 1920s and 1930s and which was the inspiration for author Mary Wesley’s coming-of-age novel The Camomile Lawn.

Such was Boskenna’s allure that guests as distinguished as Lawrence of Arabia, Albert Einstein and D.H. Lawrence were all drawn there, as well as the Italian radio pioneer Marconi, who is said to have fallen in love with Sonya’s mother, Betty.

Years later, Betty would be caught up in another drama when Paull Hill — her second husband and the man who had proudly walked 19-year-old Sonya down the aisle in 1959 — was charged with murdering his wife’s much younger lover.

Scandalously, aged 61, she’d started an affair with Scott Tuthill who, at 25, was 36 years her junior.

According to court reports from the time, Scott died in 1979 after he was shot in the leg by a 12-bore shotgun — fired by Paull after he tried to confront Betty at their house.

At his subsequent trial, Paull pleaded self-defence — and the jury believed him.

‘The jury was out for just an hour before the foreman gave the judge the ‘not guilty’ verdict,’ recounts Charlotte.

‘Hill walked from the dock out of the court doors. He said: ‘I would do it again without the slightest hesitation.’ ‘

The discovery left her ‘staggered’, she confides.

‘We went from a picture with little detail of a couple in a church in 1959 all the way back to the golden age of a country house in Cornwall. And then we come to a murder,’ she says.

Brian and Jean Staddon got married at Windsor Parish Church in September 1959

Brian and Jean Staddon got married at Windsor Parish Church in September 1959

So what happened to Betty’s daughter Sonya? She and her husband, Tim, had two sons, the first born a year after the wedding.

But their relationship must have broken down quickly, because Tim remarried seven years later. He died in America in 1997, aged 67. Sonya died in 1998, aged just 58.

Charlotte has since returned the photograph to Timothy and Sonya’s two sons — who didn’t want to take part in the documentary.

Not all the stories Charlotte has unravelled proved to be quite so dramatic, but they’re certainly enticing and heart-warming, like the June 1952 Deptford wedding of George and Kathleen Sewell.

Charlotte found their wedding album in a charity shop several years ago, and it has long been one of her favourites.

‘It was so lovingly put together, with these really lovely photos of this very smiley happy couple, along with some wedding telegrams and honeymoon receipts.

It gives a real sense of the couple they were,’ she says.

After sourcing their marriage certificate, Charlotte was able to ascertain that the 36-year-old bride was a nursing officer, while her older 52-year-old groom had marked his profession as ‘film director’.

‘That caught my attention,’ says Charlotte.

In fact, George was something of a pioneer: a passion for moving pictures had been forged in the unlikely setting of the World War I trenches, when, aged 18 and serving in the London Regiment, he had volunteered to play background music on the piano when a silent movie was screened for the entertainment of the troops.

By 1932, he had written the first book on amateur film-making.

The same decade, he founded the Institute of Amateur Cinematographers, an organisation that exists to this day.

The wedding of George and Kathleen Sewell in June 1952 in Deptford

The wedding of George and Kathleen Sewell in June 1952 in Deptford

‘George is dead — it seems unbelievable as he has been part of the movie-making scene as long as there has been a movie-making scene,’ the obituary reads.

‘In fact, he was the ringleader of the small group that started it way back in the 1920s.’

What’s more, some of his filmmaking also survives to this day, including a short film called The Gaiety Of Nations about the origins and effects of the Great War.

‘It was made 91 years ago but shows real expertise and love of the medium,’ says Charlotte. ‘It was spine-tingling watching it.’

After the war, George became a journalist and professional director, while he and Kathleen continued to live in the Middlesex home they moved into when they married.

Sadly, as the couple had no children, following Kathleen’s death in 2013 there was no one to take ownership of their album which, like so many others, was likely to have been lost through house clearance.

Unable to find any living relatives, Charlotte ultimately handed the album over to the Institute of Amateur Cinematographers.

‘It felt like the right place to go and I think George in particular would have been pleased,’ she says.

She found a home, too, for the wedding album of Brian and Jean Staddon, who had married at Windsor Parish Church in September 1959 and whose pictures had been taken by a well-known local photographer Kingsley Jones — a useful starting point for research.

Like Kathleen and George, the couple had no children, but after learning that Brian had died in Weymouth in 2017, Charlotte contacted the funeral directors who had organised his funeral and were put in touch with Philip and Maureen de Havilland, who had overseen the arrangements and turned out to be the couple’s best friends of 40 years standing.

Charlotte learned the story of their enduring friendship, which started in 1977 when Brian and Philip both started work as prison officers at a prison in Portland.

The couples loved to socialise together, while Jean and Brian had lovingly adopted the role of godparents to two of the de Havillands’ daughters.

‘Jean had made both their wedding cakes and decorated their wedding car,’ says Charlotte.

It was the de Havillands whom Jean asked to accompany her and Brian on a valedictory cruise on the QE2 after learning in 2006 she had terminal stomach cancer and, following her death the following year, the de Havillands continued to look after her widower.

‘They were best friends who were more like family,’ says Charlotte.

‘Brian and Jean just came across as lovely ordinary people who were so in love with each other until the end — and giving their friends their wedding album felt like the right thing to do.

And while she confides that parting with her photographs can be difficult, she hopes nonetheless to do it many more times in the future.

‘You do become attached,’ she admits. ‘At the same time, I don’t think of myself as their owner but their custodian.’

With the rapid advance of technology there is, of course, every chance that in due course the wedding album could become a thing of the past, as young newlyweds increasingly place their memories on their laptops and mobile phones.

‘It kills me to say it but there is definitely less emphasis on albums — although I think people still like to have a framed photograph or two in their home,’ Charlotte says.

Either way, she has one message for those newlyweds picking up their prints from the developer.

‘I really encourage everybody to label their photos,’ she says. ‘One day someone will thank you for it.’

The second of three parts of The Wedding Detectives can be heard on Radio 4 today at 11am.

Last week’s episode can be found on BBC Sounds.

Meet the first woman to run for president

Meet the first woman to run for president

The hill/ by Morgan Chalfant

https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/518301-meet-the-first-woman-to-run-for-president

© Library of Congress

© Library of Congress

The first woman to formally declare herself a candidate for president of the United States did not build a national campaign or make a splash in debates. In fact, when Victoria Woodhull ran for office in 1872, she could not even vote for herself.

Woodhull, an unconventional social reformer who advocated for “free love” and women’s suffrage, was nominated to run for president by the newly established Equal Rights Party. Her run came decades before the ratification of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote.

Born Victoria Claflin, she came from humble roots in Homer, Ohio. She received essentially no formal education, though she and her sister Tennessee Claflin worked as traveling medical clairvoyants.

Woodhull fell ill at the age of 14 and eventually married the man who treated her, Canning Woodhull, when she was 15. He was her first of three husbands, one who didn’t bother to stop womanizing.

“She was fully aware at that time that there were men who had affairs like her husband and women were just stuck,” said Teri Finneman, an associate professor in the University of Kansas’s school of journalism and author of “Press Portrayals of Women Politicians.” “She found that to be grossly unfair and hypocritical, and that would help to greatly influence her views during the campaign.”

Woodhull and her sister established a relationship with Cornelius Vanderbilt, a wealthy railroad magnate, through their work as traveling clairvoyants. With his backing, they settled in New York in the 1860s and together started the first female-run stock brokerage company, which attracted plenty of press coverage and brought her to the attention of suffrage advocates.

The sisters used money they earned from the firm to establish a women’s rights and reform newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, which published the first English translation of “The Communist Manifesto” and served as an outlet for discussion of women’s suffrage and other issues. The newspaper advocated for issues like a single moral standard for the sexes and legalizing prostitution.

Woodhull became an unusual and prominent advocate for women’s suffrage at the height of her public career, which paved the way for her run for president.

She became the first woman to address a House committee on Jan. 11, 1871, delivering a speech before the House Judiciary Committee about women’s suffrage.

Woodhull, joined by famed women’s suffrage advocates Susan B. Anthony and Isabella Beecher Hooker, argued in her address that the 14th and 15th amendments implicitly afforded women the right to vote. She implored the committee to draft legislation giving women the right to vote, but they rejected her appeal.

Woodhull clashed with more conservative suffrage advocates like Anthony, who found Woodhull’s ideals too liberal.

Woodhull was nominated for president by the Equal Rights Party to run against incumbent Republican Ulysses Grant and Horace Greely, the Democratic nominee, in 1872. The party platform covered a range of issues, including abolishing monopolies, a single form of currency, an end to war, direct and equal taxation, help for the unemployed and free trade.

“While others of my sex devoted themselves to a crusade against the laws that shackle the women of the country, I asserted my individual independence; while others prayed for the good time coming, I worked for it; while others argued the equality of woman with man, I proved it by successfully engaging in business; while others sought to show that there was no valid reason why woman should be treated socially and politically as a being inferior to man, I boldly entered the arena of politics and business and exercised the rights I already possessed,” Woodhull wrote in a letter to the editor published in the New York Herald announcing her candidacy.

“I therefore claim the right to speak for the unenfranchised women of the country,” she wrote.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was nominated as Woodhull’s running mate, though he did not accept.

Woodhull did not win any electoral votes, but her run represented a step forward for women seeking a seat at the table in politics.

“I think it did send a signal to political elites and members of our political institutions that this was an issue they would need to address,” said Jennifer Lawless, a politics professor at the University of Virginia. “Questions of women’s political inclusion were not only going to be about the right to vote.”

The press coverage of her presidential run was overwhelmingly critical. Cartoonist Thomas Nast depicted Woodhull in demonic garb and labeled her “Mrs. Satan.”

“Being the first is always difficult, and so the fact that she did that, that she put herself out there, she definitely put the crack in the ceiling,” said Finneman. “What is frustrating today is how some of that same media vilification that she faced in 1872 has continued to be a thread in culture and media coverage of women even to this day.”

Finneman pointed to the coverage of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run and of former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin when she was chosen as Sen. John McCain’s (R-Ariz.) running mate in 2008.

Woodhull is not typically listed among the names of prominent women’s rights advocates in present day, and experts say she has been overlooked likely because of her unconventional background and embrace of some controversial ideas.

In the waning days of her presidential campaign, Woodhull found herself embroiled in controversy. She and her sister were arrested three days before Election Day and thrown in New York City jail on obscenity charges for publishing a report in their newspaper about an alleged affair between Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and a married parishioner.

They were acquitted after several months of litigation, but Woodhull spent Election Day in prison, preventing her from any attempt at casting a ballot for herself.

Woodhull eventually sought a new start with her sister in England, after divorcing her second husband in 1876. She married an English banker in 1883 and went on to publish a number of works, including the magazine Humanitarian, which was focused on eugenics.

She died in England in 1927, at the age of 88.

An anti-abortion protest “National March for Life,” demanding a ban on abortions, in Bratislava, Slovakia on September 2019.

An anti-abortion protest “National March for Life,” demanding a ban on abortions, in Bratislava, Slovakia on September 2019.