Britain’s monarch has long occupied two roles — one as the head of the state and nation, the other as the head of her own family — and over the past 12 months she has been forced to confront crises on both fronts.

Here’s a look back at one of the Queen’s most challenging years to date.

The Duke and Duchess of Sussex said in a bombshell statement on their official Instagram account on January 8 they hoped to continue supporting the monarch but wanted to seek financial autonomy. The pair credited the Queen with providing the encouragement “particularly over the last few years” that led them to make such a dramatic announcement.

But CNN understands

conversations over the couple’s future were already underway and the Queen was “disappointed” that her grandson had opted to reveal as much publicly. The monarch had explicitly told Harry to continue negotiations privately and was said to been left “upset.”

Prince Harry and Meghan depart Canada House on January 7 in London, England

Harry and Meghan had hoped to carve out a role the establishment had never seen before, a hybrid position where they would choose which formal positions they would keep and which they would leave behind while they developed their own private income streams and independence. It’s clear they also felt unsupported and unprotected by the palace machinery against what they felt was

a constant barrage of media abuse and lies.

But royal roles are in the gift of the monarch, and the Sussexes’ “half-in, half-out” model wasn’t seen as workable. The Queen was left in the uncomfortable predicament of trying to give her beloved grandson what he wanted without compromising the institution. It was perhaps the most delicate moment for the British monarchy since the aftermath of

Diana‘s death in 1997.

The situation culminated in a crisis

summit at her Sandringham residence where she was joined by the heir to the throne Prince Charles, his elder son Prince William and Harry. In a statement after the meeting, the Queen said Harry, Meghan and their son Archie would “always be much loved members of my family.”

“I recognize the challenges they have experienced as a result of intense scrutiny over the last two years and support their wish for a more independent life,” she said. “I want to thank them for all their dedicated work across this country, the Commonwealth and beyond, and am particularly proud of how Meghan has so quickly become one of the family.”

The terms of the split stipulated that while the pair would always remain part of the family, they would no longer use their HRH titles; they would receive financial assistance from Charles, and could

supplement their income with appropriate opportunities.

Harry’s frustration over the result was evident. “It brings me great sadness that it has come to this. The decision that I have made for my wife and I to step back is not one I made lightly,”

he told a charity event in London in late January.

“Our hope was to continue serving the Queen, the Commonwealth, and my military associations, but without public funding. Unfortunately, that wasn’t possible.”

By the end of March, Harry and Meghan’s transition out of their royal roles was complete. The current arrangements are due to be reviewed by the Sussexes and the rest of the family in March.

It was a dramatic start to the year, but arguably left the monarchy in a stronger position. The Crown can modernize as much as it likes, but ultimately it’s built on a hierarchy, and the direct line of succession — Elizabeth, Charles and William — showed a united front.

Having settled the family drama, the Queen was immediately presented with one the biggest crises she’s ever faced as head of nation — keeping everyone united as the Covid-19 pandemic hit and the country went into an uncomfortable lockdown.

As Covid-19 spread through the UK, she was prevented from doing what she does best when her busy

diary of public engagements was suddenly curtailed. She made the decision to relocate from Buckingham Palace in London to form a bubble in

Windsor with Prince Philip and key staff “as a sensible precaution.”

Prince Charles is seen on a monitor as he speaks during the opening of the “NHS Nightingale” field hospital, at the ExCeL London exhibition center, in London on April 3.

Those words rang true days later, when Prince Charles announced he had

tested positive for the coronavirus. The Prince of Wales was said to have had only mild symptoms and is otherwise in good health, but the mere fact that the 71-year-old was unwell emphasized to all how the virus did not discriminate.

William also caught Covid-19 in the spring, but only revealed it later in the year, telling an “observer” that he opted not to go public with his diagnosis because “there were important things going on and I didn’t want to worry anyone.” His decision to initially withhold news of his illness from the public sparked some criticism.

As cases and deaths from the virus across the UK started to spiral in April, so too did criticism of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s handling of the pandemic. In co-ordination with Downing Street, the Queen agreed to address the nation in a televised speech.

“I am speaking to you at what I know is an increasingly challenging time. A time of disruption in the life of our country: a disruption that has brought grief to some, financial difficulties to many, and enormous changes to the daily lives of us all,” the Queen

said in early April.The Queen seldom makes national addresses, save for Christmas and when a new Parliament is installed. The moment was a somber but reassuring acknowledgment of the hardships society was facing. News channels the world over — including CNN — broke in as the pre-recorded video was broadcast to the UK and the 54 nations of the Commonwealth.

In the speech, she drew on her first broadcast alongside her sister Princess Margaret in 1940 to relay that the nation and those watching would overcome the current crisis.

“We, as children, spoke from here at Windsor to children who had been evacuated from their homes and sent away for their own safety. Today, once again, many will feel a painful sense of separation from their loved ones. But now, as then, we know, deep down, that it is the right thing to do,” she said, while also thanking frontline healthcare professionals.

Royal expert and historian Kate Williams said the speech sounded a note of hope that many Britons needed to hear in that moment.

“It’s so rare that she gives an address [and] the address she gave was so striking,” Williams said. “It was dark days when everyone was very isolated, [and] couldn’t go out at all … it was a quite brilliantly delivered speech.”

That optimistic sentiment — which she would echo in other 2020 speeches marking events like Easter and the 75th anniversary of VE Day — reasserted her role as a hands-on leader and set the tone for how she and her family would conduct themselves for the remainder of the year. After imploring the public to remain at home, the royal family transitioned from walkabouts to video calls, embracing a new work-from-home life like millions of other Britons.

“We all knew Brexit was coming, but Covid is what we didn’t see coming … the Queen feels it’s her job to lead by example and to hold leaders to account,” Williams said. “I don’t think it’s been easy for her not being able to have face-to-face meetings with the Prime Minister — that’s what she prefers.

“This is one of the great crises of recent British history. More people have died than in the Blitz. It is like the war. I don’t think that she thought she was going to have a quiet few years in her 90s but … a lot of what she’s seen are political crises and diplomatic conflicts and conflicts, and this is very different. It cannot be solved by getting people together around a table.”

The Queen would not reopen the royal diary of engagements until July 17, when she knighted

Captain Thomas Moore — the 100-year-old World War II veteran who had raised millions for the UK’s National Health Service. Hours earlier, she had attended a private wedding ceremony for her granddaughter

Princess Beatrice. And as the spring wave finally abated, members of the royal family resumed socially distanced engagements with the public at foodbanks, hospitals and businesses hit by the pandemic.

Williams said it has always been very important to the Queen to be there for the public and it will have been hard for her that Covid has limited her movements. She says the Queen knows for monarchy to work “it needs to be seen.”

“It’s part of the contract it has with the people. It doesn’t work if you just sit in the palace,” she added. “Monarchy has had to completely reinvent in the same way that businesses have had to.”

It hasn’t been a year entirely untainted by scandal: lingering questions remain over Prince Andrew’s relationship with the late American financier Jeffrey Epstein. The Queen never said anything publicly about the matter, but she made a major statement in accepting what was billed as Andrew’s decision to step back from public duties. The move came in the wake of Andrew’s disastrous interview with the BBC in late 2019, when he denied having sex with an underage girl and said he had seen nothing suspicious when he was around Epstein, a convicted pedophile. It would have been a painful decision for both Andrew and his mother but ultimately one that again she felt was right for the institution.

The latter part of the year also saw the family face several other challenges.

In October, the Queen undertook her first public engagement since the spring lockdown — a

visit to Porton Down science park in southern England with William. But she was criticized by some for not wearing a mask despite a resurgence in the virus. In response, Buckingham Palace said the Queen had chosen to forego a mask after consulting her own medics and scientists at the military research facility. Social distancing guidelines were in place at the event and everyone the British monarch met had tested negative for the virus. A month later, she appeared in a mask

for the first time at a commemorative ceremony in London.

The Queen during a ceremony in Westminster Abbey to mark the centenary of the burial of the Unknown Warrior on November 4.

The latest installment of “The Crown” brought a fresh flurry of international interest to palace gates in November. The fourth season of the Netflix drama heralded the arrival of Princess Diana, and painted Charles as a petulant prince and cruel husband. Critics said the portrayal of Charles — along with a number of other scenes — was inaccurate, and it prompted a call from one UK government official for Netflix to tack an extra disclaimer onto each episode of series.

“It’s a beautifully produced work of fiction, so as with other TV productions, Netflix should be very clear at the beginning it is just that,” Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden told the

UK’s Mail on Sunday. “Without this, I fear a generation of viewers who did not live through these events may mistake fiction for fact.” Netflix refused to add the warning to the show.

And in December, several family members were accused of breaking coronavirus regulations. In pictures published by The Mail Online, William and his family appeared to be walking alongside his uncle Prince Edward and his family during an outing to a Christmas-themed woodland walk. The photographs seemingly contravened England virus rules, which limits outdoor gatherings to just six people.

The Queen and members of the royal family gave thanks to local volunteers and key workers for their work in helping others during the coronavirus pandemic and over Christmas at Windsor Castle on December 8.

Like millions of Britons, the monarch sacrificed the traditional holiday festivities with her family at Sandringham. Instead, for the first time in 33 years, she remained at Windsor with 99-year-old Prince Philip.

The situation is a fitting way to end the year, according to royal historian Williams. “It’s unprecedented for them to be spending it just the two of them. Even in the war, [Christmas] was a big family time,” she said.

The Queen acknowledged what a sad and unusual festive season it would be for many in her

annual Christmas speech, assuring those missing out on time with loved ones, and whose only wish was for “a simple hug or a squeeze of the hand,” that “

you are not alone.”

This year has seen the world grapple with something nobody could have predicted 12 months ago. For the Queen’s part, she has reaffirmed her position as the unifier-in-chief for family, and for nation.

At a time in her life when she might be expected to step back, the Queen has shown she is still in charge, even as she delegates more duties to Charles and William. Any rumors that she plans to abdicate and handover the crown have been quashed for another year.

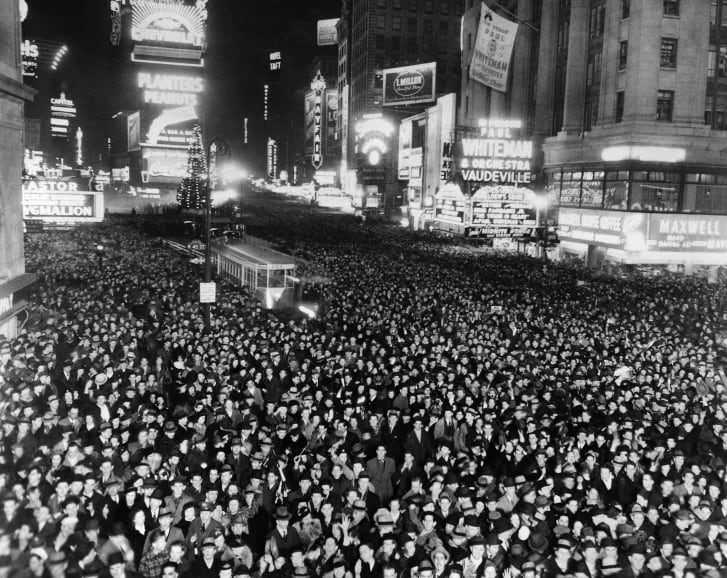

New Year’s Eve has its own set of rituals: the ball drop, resolutions and sealing the new year with a kiss.

New Year’s Eve has its own set of rituals: the ball drop, resolutions and sealing the new year with a kiss. The Times Square Ball has had seven different designs.

The Times Square Ball has had seven different designs.