From My Modern Met/By Sara Barnes /October 27, 2020

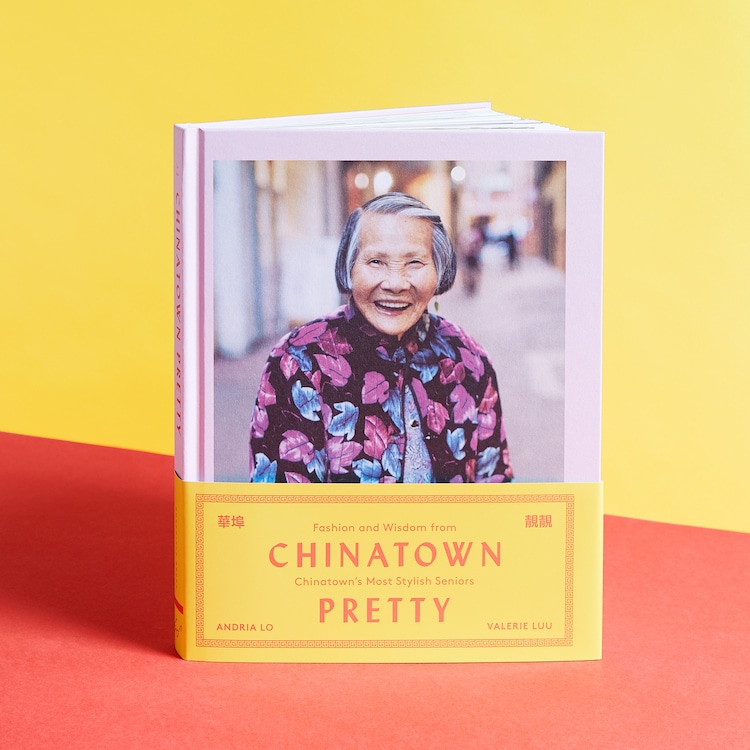

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Senior citizens seem like unlikely sources of statement-making style; but as Andria Lo and Valerie Luu show in their book Chinatown Pretty, grandparents—specifically those in Chinatowns across North America—are unintentional fashion icons. Also known as “poh pohs” and “gung gungs” (grandmas and grandpas, respectively), the authors share portraits of the impeccably dressed city dwellers in San Francisco, Chicago, Vancouver, and beyond.

The folks featured in Chinatown Pretty aren’t afraid to buck fashion conventions. They mix patterns or wear contrasting colors that some might say clash. Floral printed shirts are worn underneath plaid blazers and lighter jackets are layered with heavy coats that are accented with a mismatching scarf. On the hanger, these combinations don’t work. But when on the body and worn with the right mindset, the outfits have a fashionable ease about them. “Some of the magic we observe in the Chinatown style is that it’s quite effortless and unexpected,” the authors tell My Modern Met. “Pieces that shouldn’t really work together, that clash or are from different eras, end up having their own unique harmony.”

Chinatown Pretty includes inspiring fashion as well as the stories of the stylish seniors that Lo and Luu encountered when writing the book. We spoke with the authors about the documenting process as well as what younger people can learn from the older generation. Scroll down to read our exclusive interview.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

What was the inspiration for Chinatown Pretty?

The style was intriguing to us and we wanted to know more—who were these women and where did they get their shoes?

We decided to investigate. We found that asking about their clothes was a great way to learn about this generation and hear some fascinating perspectives that are often not brought to light.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Why do you think that grandmas and grandpas have such a great sense of style?

A lot of the “trends” we see are rooted in Chinatown’s history and Chinese culture. We’ve learned from talking to subjects that their garments are often handmade (women were able to get jobs in garment factories without knowing English) or brought over to the U.S. when they immigrated, and they’ve retained those pieces through the decades.

What about their sartorial choices makes them so fashionable?

There’s a certain je ne sais quoi with Chinatown seniors—it often involves outfits that play with bold colors, patterns, and handmade or customized clothing and accessories. Some of the magic we observe in the Chinatown style is that it’s quite effortless and unexpected. Pieces that shouldn’t really work together, that clash or are from different eras, end up having their own unique harmony.

There is an appreciation for color, pattern, and dressing pragmatically—layering up and keeping warm, while also keeping the sun out with baseball caps or long-billed visors. It’s not uncommon for us to see folks six or more layers deep in clothing, even in the warmer months!

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Is there a look that one subject wore that is particularly memorable for you?

Ms. Yang had a wonderful silver bob that she cut herself and an oversized plaid blazer and pops of color that definitely got our heart racing. She lives in an affordable housing building for seniors in San Francisco Chinatown. We sat down in her apartment to interview her with her daughter, she told us she had Alzheimer’s and can’t remember her past too much. But she says that she’s healthy and her kids and grandkids are also healthy and good. We really liked her attitude, letting go of control, and being happy with what she has.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

In approaching these people about their style, you learned a lot about their backstories. Do you think this informed their overall sense of style?

Chinatown Pretty, in addition to being about interesting fashion, has allowed us to learn more about Chinese American history. Clothes are a gateway to the seniors’ life stories and immigration journeys. San Francisco has a rich immigration history—from people coming here during the Gold Rush to building railroads to working in restaurants and garment factories—and Chinatown has been a landing pad for many of the people profiled in the book. The cultural values and histories of Chinatown seniors are reflected in their clothes. Reusing, repurposing, functionality, making their own clothes, keeping warm (layering) and sun protection are all values that emerge in this style.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

What was the process like in putting together this book?

Putting together the book involved traveling to a few new Chinatowns—Chicago and Vancouver—and going out to shoot new people in all the other cities we’ve been to before. There were lots of rainy days walking around Chicago and New York Chinatown as we went scouting in the spring of 2018.

Were there any unexpected things you learned or challenges with writing it?

With writing, there was a challenge of striking a happy balance between providing Chinatown history and capturing Chinatown as they are today. One would not exist without the other—but our primary goal was capturing the seniors and the neighborhoods as they are right now. So it’s 20% history and 80% a snapshot of the individuals that we were able to meet and the information we were able to gather in the sweet and short serendipitous encounters with them.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

What can the younger generations learn from these fashionable grandmas and grandpas?

We’re struck and inspired by how the seniors live an independent lifestyle well into their 80s and 90s. They are active city dwellers, walking and using public transit, exercising and socializing in public parks, and shopping local!

Also through this project, we’ve gotten to learn about and partner with nonprofits in various Chinatowns that do important work to preserve and protect the community. There is a lot of behind the scenes effort to help Chinatowns continue to be livable neighborhoods.

What can readers expect from your book?

There are a total of 113 stories, many that you won’t find on our Instagram or blog, and a lot of the stories are longer and more in-depth. It’s a book you’ll want to soak up and slowly observe the details of. In COVID times, we can’t mingle or meet up in person as much, but we hope through this book, readers will feel like they’re getting to know some new friends or neighbors.

See more stylish senior citizens from Chinatown Pretty:

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020

Chinatown Pretty: Website | Instagram | Facebook

Chinatown Pretty Book: Chronicle Books | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Green Apple Books

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Chronicle Books.

Brian and Jean Staddon got married at Windsor Parish Church in September 1959

Brian and Jean Staddon got married at Windsor Parish Church in September 1959 The wedding of George and Kathleen Sewell in June 1952 in Deptford

The wedding of George and Kathleen Sewell in June 1952 in Deptford

© Library of Congress

© Library of Congress