Waves are local—the brushing of the ocean by the wind. Swells roll for thousands of miles across open water, unaffected by the weather of the moment.

On January 24, 2019, the Pressure Drop set off from the port of Montevideo, Uruguay, to dive the South Sandwich Trench, the deepest point of the Southern Ocean. Buckle and his crew had loaded the ship with cold-weather gear, and provisions for more than a month. There was a five-thousand-mile journey ahead of them, and the ship could barely go nine knots.

“Captain, can I have a word?” Peter Coope, the chief engineer, asked. “Is this ship going to be O.K.?”

“Yes,” Buckle replied. “Do you think I would invite on board all the people I like working with most in the world, and then sail us all to a certain death?”

But Buckle wasn’t so sure. A year earlier, when he’d first walked up the gangplank, he wondered why Triton had chosen this ship. The Pressure Drop hadn’t been in service in several years. The hull was watertight, but there were holes in the steel superstructure, and the shipyard had stripped every functional component. The steering system had been wired in reverse; turn one way and the ship went the other. “It’s a classic case of people who have spent a lot of time on boats thinking they know boats,” Buckle told me. “I’ve spent a lot of time on planes, but if Victor said, ‘I want to buy a 747,’ I wouldn’t go up and say, ‘Yes, that one is great—buy that one.’ I’d get a pilot or a flight engineer to do it.” Buckle’s first officer recalled, “The ship was fucking breaking apart.”

After the purchase, Buckle and a small crew of mostly Scottish sailors spent two months living near a dock yard in Louisiana, refitting and repairing the ship. “Stu took a huge risk—not only for himself but for all his officers,” McCallum told me. “He handpicked the guys, pulled them off of very well-paying oil-and-gas jobs, and got them to follow him to bumfuck nowhere.” In the evenings, Buckle and his crew drank beer on the top deck, and tossed pizza slices to alligators in the bayou. The ship came with no manuals, no electrical charts. “It was just a soul-destroying, slow process,” Buckle said.

Now Buckle was steering the Pressure Drop into the Southern Ocean, the site of the most reliably violent seas in the world. After a few nights, Erlend Currie, a sailor from the Orkney Islands, shoved a life jacket under the far side of his bunk, so that the mattress would form a U shape, and he wouldn’t fall out.

“You get these nasty systems rolling through, with just little gaps between them,” McCallum told me. McCallum has seen waves in the Southern Ocean crest above ninety feet. He had carefully mapped out a dive window, between gales, and brought on board an ice pilot and a doctor. “If something goes wrong, there’s no port to go to, and there’s no one to rescue you,” he said.

Albatross trailed the ship for the first several days. Soon they disappeared and the crew began seeing whales and penguins. “Filled with trepidation, we steamed into the teeth of the area where, on the old maps, they used to write, ‘Here Be Monsters,’ ” Vescovo told me.

On the forecastle deck, in the control room, a cheerful, brown-haired Texan named Cassie Bongiovanni sat before four large monitors, which had been bolted to the table. Bongiovanni, who is twenty-seven years old, was finishing a master’s degree in ocean mapping at the University of New Hampshire when Rob McCallum called and said that he needed someone to run a multibeam sonar system for one and a half laps around the world. She graduated at sea while mapping Vescovo’s dive location in the Puerto Rico Trench.

As the head sonar operator, Bongiovanni had to make perfect decisions based on imperfect information. “The sound is generated from the EM-124, housed inside the giant gondola under the ship,” she said. “As it goes down, the width of each sound beam grows, so that in the deepest trenches we’re only able to pick up one point every seventy-five metres or so.” In these trenches, it takes at least seven seconds for sound to reach the bottom, and another seven seconds to return. In that gap, the ship has moved forward, and has pitched and rolled atop the surface of the sea. Bongiovanni also had to account for readings of sound speed at each dive site, as it is affected by variations in temperature, salinity, and depth.

The purchase and installation of the EM-124 cost more than the ship itself, but its software was full of bugs. Each day, Bongiovanni oscillated between awe and frustration as she rebooted it, adjusted parameters, cleaned up noisy data, and sent e-mails to Kongsberg, the maker, to request software patches. The expedition wasn’t merely the first to dive the South Sandwich Trench but the first to map it as well.

Steve Chappell, a Triton mechanic, was one of a few crew members assigned the role of “swimmer,” leaping into the water and disconnecting the towline from the Limiting Factor before it descended.

Steve Chappell, a Triton mechanic, was one of a few crew members assigned the role of “swimmer,” leaping into the water and disconnecting the towline from the Limiting Factor before it descended.

Buckle positioned the ship over the dive site. A Triton mechanic named Steve Chappell was assigned the role of “swimmer,” meaning that he would balance atop the Limiting Factor as it was lowered into the water, and disconnect the towline before it went down. He wore a dry suit; polar waters can rapidly induce involuntary gasping and vertigo, and even talented swimmers can drown within two minutes. For a moment, he lay on a submarine bucking in the middle of the Southern Ocean, fumbling with wet ropes, fingers numb. Then a Zodiac picked him up and took him back to the Pressure Drop, where he warmed his hands by an exhaust vent. Vescovo started the pumps, and the Limiting Factor began its descent.

Dive protocols required that Vescovo check in with the surface every fifteen minutes and announce his depth and heading and the status of his life-support system. But, after forty-five hundred metres, the communications system failed. The ship could still receive Vescovo’s transmissions, but Vescovo couldn’t hear the replies.

Aphids and krill drifted past the viewports. It is customary to abort a dive thirty minutes after losing communications, but Vescovo knew that he might never have another chance to reach the bottom of the Southern Ocean, so he kept going. He liked the sensation of being truly alone. Sometimes, on the surface, he spoke of human nature as if it were something he had studied from the outside. Another hour passed before he reached the deepest point: seven thousand four hundred and thirty-three metres. The point had never been measured or named. He decided to call it the Factorian Deep.

That night, Alan Jamieson, the chief scientist, stood on the aft deck, waiting for biological samples to reach the surface. “Most marine science is gritty as fuck,” he told me. “It’s not just ‘Look at the beautiful animal,’ or ‘Look at the mysteries of the deep.’ It’s all the weird vessels we end up on, the work of hauling things in and out of the water.” Jamieson, a gruff, forty-two-year-old marine biologist, who grew up in the Scottish Lowlands, is a pioneer in the construction and use of hadal landers—large, unmanned contraptions with baited traps and cameras, dropped over the side of a ship. In the past two decades, he has carried out hundreds of lander deployments in the world’s deep spots, and found evidence of fish and critters where none were thought to be. Now, as snow blew sideways in the darkness and the wind, he threw a grappling hook over the South Sandwich Trench and caught a lander thrashing in the waves.

There were five landers on board. Three were equipped with advanced tracking and communications gear, to lend navigational support to the sub underwater. The two others were Jamieson’s—built with an aluminum frame, disposable weights, and a sapphire window for the camera, to withstand the pressure at depth. Before each dive, he tied a dead mackerel to a metal bar in front of the camera, to draw in hungry hadal fauna. Now, as he studied the footage, he discovered four new species of fish. Amphipods scuttled across the featureless sediment on the seafloor, and devoured the mackerel down to its bones. They are ancient, insect-like scavengers, whose bodies accommodate the water—floating organs in a waxy exoskeleton. Their cells have adapted to cope with high pressure, and “they’ve got this ridiculously stretchy gut, so they can eat about three times their body size,” Jamieson explained. Marine biologists classify creatures in the hadal zone as “extremophiles.”

The following night, one of Jamieson’s landers was lost. “Usually, things come back up where you put them, but it just didn’t,” Buckle said. “We worked out what the drift was, and we then sailed in that drift direction for another three or four hours, with all my guys on the bridge—searchlights, binoculars, everyone looking for it. And we just never found it.”

On the Arctic and Antarctic dives, the swimmers wore dry suits; polar waters can induce gasping and vertigo, and even talented swimmers risk drowning within two minutes.

On the Arctic and Antarctic dives, the swimmers wore dry suits; polar waters can induce gasping and vertigo, and even talented swimmers risk drowning within two minutes.

The second one surfaced later that night. But during the recovery it was sucked under the pitching ship and went straight through the propeller. By now, there was a blizzard, and the ship was heaving in eighteen-foot waves. “I lost everything—just fucking everything—in one night,” Jamieson said. Vescovo suggested naming the site of the lost landers the Bitter Deep.

The Pressure Drop set off east, past a thirty-mile-long iceberg, for Cape Town, South Africa, to stop for fuel and food. Bongiovanni left the sonar running, collecting data that would correct the depths and the locations of key geological features, whose prior measurements by satellites were off by as much as several miles. (Vescovo is making all of the ship’s data available to Seabed2030, a collaborative project to map the world’s oceans in the next ten years.) Meanwhile, Jamieson cobbled together a new lander out of aluminum scraps, spare electronics, and some ropes and buoys, and taught Erlend Currie, the sailor from the Orkney Islands, to bait it and set the release timer. Jamieson named the lander the Erlander, then he disembarked and set off for England, to spend time with his wife and children. It would take several weeks for the ship to reach its next port stop, in Perth, where the Triton crew would install a new manipulator arm.

At the time, the deepest point in the Indian Ocean was unknown. Most scientists believed that it was in the Java Trench, near Indonesia. But nobody had ever mapped the northern part of the Diamantina Fracture Zone, off the coast of Australia, and readings from satellites placed it within Java’s margin of error.

The Pressure Drop spent three days over the Diamantina; Bongiovanni confirmed that it was, in fact, shallower than Java, and Currie dropped the Erlander as Jamieson had instructed. When it surfaced, around ten hours later—the trap filled with amphipods, including several new species—Currie became the first person to collect a biological sample from the Diamantina Fracture Zone.

The Java Trench lies in international waters, which begin twelve nautical miles from land. But the expedition’s prospective dive sites fell within Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone; according to U.N. conventions, a country has special rights to the exploration and exploitation of marine resources, as far as two hundred nautical miles from the coast. McCallum had spent much of the previous year applying for permits and permissions; he dealt with fifty-seven government agencies, from more than a dozen countries, in order to plan the Five Deeps.

For several months, the Indonesian government ignored McCallum’s inquiries. Then he was bounced among ten or more agencies, to which he sent briefing materials about the submersible, the ship, the crew, and the mission. Between the Atlantic and the Antarctic dives, Vescovo flew to Jakarta to deliver a lecture, and he offered to bring an Indonesian scientist to the bottom of the trench. But when the ship arrived in Bali McCallum still hadn’t received permission to dive.

Officially, this meant that the team could not carry out any scientific work in the Java Trench. But the international law of the sea allows for the testing of equipment, and, after Java, the next set of dives, in the Pacific Ocean, would be the deepest of all. “So we tested the sub a few times,” McCallum said, smiling. “We tested the landers, we tested the sonar—we tested everything.”

The Java Trench is more than two thousand miles long, and the site of violent seismic activity. Surveys in the northern part show evidence of landslides, from the 2004 earthquake that triggered a tsunami with hundred-foot waves that killed a quarter of a million people across Southeast Asia. Farther south, satellites had detected two deep pools, several hundred miles apart. The Pressure Drop mapped both sites, and Bongiovanni discovered that, in fact, the deepest point was between them, in a small pool that had previously gone unnoticed. It may be a new rupture in the ocean floor.

Buckle positioned the Pressure Drop over the pool, and turned off the ship’s tracking and communications equipment. McCallum hoisted a pirate flag. The climate was tropical, eighty-six degrees, the ocean calm, with slow, rolling swells and hardly a ripple on the surface. On the morning of April 5, 2019, the Triton crew launched the Limiting Factor without incident, and Vescovo dived to the deepest point in the Java Trench.

Mountaineers stand atop craggy peaks and look out on the world. Vescovo descended into blackness, and saw mostly sediment at the bottom. The lights on the Limiting Factor illuminated only a few feet forward; the acrylic viewports are convex and eight inches thick. Whatever the true topography of the rock underneath, hadal trenches appear soft and flat at the deep spots. Flip a mountain upside down and, with time, the inverted summit will be unreachable; for as long as there has been an ocean, the trenches have been the end points of falling particulate—volcanic dust, sand, pebbles, meteorites, and “the billions upon billions of tiny shells and skeletons, the limy or silicious remains of all the minute creatures that once lived in the upper waters,” Rachel Carson wrote, in “The Sea Around Us,” in 1951. “The sediments are a sort of epic poem of the earth.”

Vescovo spent three hours at the bottom, and saw a plastic bag through the viewports. In the Puerto Rico Trench, one of the Limiting Factor’s cameras had captured an image of a soda can. Scientists estimate that in thirty years the oceans will hold a greater mass of plastic than of fish. Almost every biological sample that Jamieson has dredged up from the hadal zone and tested in a lab has been contaminated with microplastics. “Does it harm the ability of these animals to feed, to maneuver, to reproduce?” McCallum said. “We don’t know, because we can’t compare one that’s full of microplastics with one that’s not. Because there aren’t any.”

The walls of trenches are filled with life, but they were not Vescovo’s mission. “It’s a little bit like going to the Louvre, putting your running shoes on, and sprinting through it,” Lahey said. “What you really want to do is to go there with someone who can tell you what you’re looking at.” The next day, Vescovo told Lahey that he could take Jamieson to the bottom of the trench. “I don’t want to go to the deepest point, because that’s boring,” Jamieson said. “Let’s go somewhere really cool.”

After a series of failures, Vescovo came close to calling off the expedition. “I think I’m just going to write this whole thing off as bad debt,” he said.

After a series of failures, Vescovo came close to calling off the expedition. “I think I’m just going to write this whole thing off as bad debt,” he said.

Four and a half miles below the ship, the Australia tectonic plate was being slowly and violently subsumed by the Eurasia plate. Bongiovanni had noticed a staircase feature coming out of a fault line, the result of pressure and breakage on a geological scale. It extended more than eight hundred feet up, beyond vertical, with an overhang—an outrageously difficult dive. Lahey would have to back up as they ascended, with no clear view of what was above the sub.

The hatch started leaking during the descent, but Lahey told Jamieson to ignore it—it would seal with pressure. It kept dripping for more than ninety minutes, and stopped only at fifteen thousand feet. “I fucking told you it would seal,” Lahey said.

The Limiting Factor arrived at the bottom just after noon. Lahey approached the fault-line wall, and headed toward some bulging black masses. From a distance, they looked to Jamieson like volcanic rock, but as Lahey drew closer more colors came into view—brilliant reds, oranges, yellows, and blues, cloaked in hadal darkness. Without the lights of the submarine, the colors may never have been seen, not even by creatures living among them. These were bacterial mats, deriving their energy from chemicals emanating from the planet’s crust instead of from sunlight. It was through this process of chemosynthesis that, billions of years ago, when the earth was “one giant, fucked-up, steaming geological mass, being bombarded with meteorites,” as Jamieson put it, the first complex cell crossed some intangible line that separates the non-living from the living.

Lahey began climbing the wall—up on the thrusters, then backward. Jamieson discovered a new species of snailfish, a long, gelatinous creature with soft fins, by looking through a viewport. The pressure eliminates the possibility of a swim bladder; the lack of food precludes the ossification of bones. Some snailfish have antifreeze proteins, to keep them running in the cold. “Biology is just smelly engineering,” Jamieson said. “When you reverse-engineer a fish from the most extreme environments, and compare it to its shallow-water counterparts, you can see the trade-offs it has made.”

The wall climb took an hour. When the last lander surfaced, Jamieson detached the camera and found that it had captured footage of a dumbo octopus at twenty-three thousand feet—the deepest ever recorded, by more than a mile.

The Pressure Drop set off toward the Pacific Ocean. McCallum lowered the pirate flag. Seven weeks later, Jamieson received a letter from the Indonesian government, saying that his research-permit application had been rejected, “due to national security consideration.”

By the end of the expedition, the ship and submarine crews had so perfected the launch and recovery that, even in rough seas, to an outsider it was like watching an industrial ballet.

By the end of the expedition, the ship and submarine crews had so perfected the launch and recovery that, even in rough seas, to an outsider it was like watching an industrial ballet.

Buckle sailed to Guam, with diversions for Bongiovanni to map the Yap and Palau Trenches. Several new passengers boarded, one of whom was unlike the rest: he had been where they were going, six decades before. Hadal exploration has historically prioritized superlatives, and an area of the Mariana Trench, known as the Challenger Deep, contains the deepest water on earth.

On January 23, 1960, two men climbed into a large pressure sphere, which was suspended below a forty-thousand-gallon tank of gasoline, for buoyancy. One of them was a Swiss hydronaut named Jacques Piccard, whose father, the hot-air balloonist Auguste Piccard, had designed it. The other was Don Walsh, a young lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, which had bought the vehicle, known as a bathyscaphe, and modified it to attempt a dive in the Challenger Deep.

The bathyscaphe was so large that it had to be towed behind a ship, and its buoyant gasoline tank was so delicate that the ship couldn’t travel more than one or two miles per hour. To find the dive site, sailors tossed TNT over the side of the ship, and timed the echo reverberating up from the bottom of the trench. There was one viewport, the size of a coin. When the bathyscaphe hit the bottom, stirring up sediment, “it was like looking into a bowl of milk,” Walsh said. A half century passed before anyone returned.

The bathyscaphe never again dived to hadal depths. Jacques Piccard died in 2008. Now Don Walsh, who was eighty-eight, walked up the gangway of the Pressure Drop. It was a short transit to the Mariana Trench, across warm Pacific waters, over six-foot swells.

Above the Challenger Deep, Vescovo pulled on a fire-retardant jumpsuit, and walked out to the aft deck. A gentle wind blew in from the east. Walsh shook Vescovo’s hand. Vescovo climbed into the Limiting Factor, carrying an ice axe that he had brought to the summit of Mt. Everest.

Hatch secured, lift line down, tag lines released, towline out—pumps on. Vescovo wondered, Is the sub able to handle this? He didn’t think it would implode, but would the electronics survive? The thrusters? The batteries? Besides Walsh and Piccard, the only other person to go to the bottom of the Challenger Deep was the filmmaker James Cameron, in 2012. Multiple systems failed at the bottom, and his submersible never dove deep again.

The depth gauge ticked past ten thousand nine hundred metres, thirty-six thousand feet. After four hours, Vescovo started dropping variable ballast weights, to slow his descent. At 12:37 P.M., he called up to the surface. His message took seven seconds to reach the Pressure Drop: “At bottom.”

Outside the viewports, Vescovo saw amphipods and sea cucumbers. But he was two miles beyond the limits of fish. “At a certain point, the conditions are so intense that evolution runs out of options—there’s not a lot of wiggle room,” Jamieson said. “So a lot of the creatures down there start to look the same.”

Vescovo switched off the lights and turned off the thrusters. He hovered in silence, a foot off the sediment bottom, drifting gently on a current, nearly thirty-six thousand feet below the surface.

That evening, on the Pressure Drop, Don Walsh shook his hand again. Vescovo noted that, according to the sonar scan, the submarine data, and the readings from the landers, he had gone deeper than anyone before. “Yeah, I cried myself to sleep last night,” Walsh joked.

The Triton team took two maintenance days, to make sure they didn’t miss anything. But the Limiting Factor was fine. So Vescovo went down again to retrieve a rock sample. He found some specimens by the northern wall of the trench, but they were too big to carry, so he tried to break off a piece by smashing them with the manipulator arm—to no avail. “I finally resorted to just burrowing the claw into the muck, and just blindly grabbing and seeing if anything came out,” he said. No luck. He surfaced.

Hours later, Vescovo walked into the control room and learned that one of the navigation landers was stuck in the silt. He was in despair. The lander’s batteries would soon drain, killing all communications and tracking—another expensive item lost on the ocean floor.

“Well, you do have a full-ocean-depth submersible” available to retrieve it, McCallum said. Lahey had been planning to make a descent with Jonathan Struwe, of the marine classification firm DNV-GL, to certify the Limiting Factor. Now it became a rescue mission.

When Lahey reached the bottom, he began moving in a triangular search pattern. Soon he spotted a faint light from the lander. He nudged it with the manipulator arm, freeing it from the mud. It shot up to the surface. Struwe—who was now one of only six people who had been to the bottom of the Challenger Deep—certified the Limiting Factor’s “maximum permissible diving depth” as “unlimited.”

The control room was mostly empty. “When Victor first went down, everyone was there, high-fiving and whooping and hollering,” Buckle said. “And the next day, around lunchtime, everyone went ‘Fuck this, I’ll go for lunch.’ Patrick retrieves a piece of equipment from the deepest point on earth, and it’s just me, going, ‘Yay, congratulations, Patrick.’ No one seemed to notice how big a deal it is that they had already made this normal—even though it’s not. It’s the equivalent of having a daily flight to the moon.” McCallum, in his pre-dive briefings, started listing “complacency” as a hazard.

The crew quickly became accustomed to the expedition’s achievements. “No one seemed to notice how big a deal it is that they had already made this normal—even though it’s not,” Buckle said. “It’s the equivalent of having a daily flight to the moon.”

The crew quickly became accustomed to the expedition’s achievements. “No one seemed to notice how big a deal it is that they had already made this normal—even though it’s not,” Buckle said. “It’s the equivalent of having a daily flight to the moon.”

Vescovo was elated when the lander reached the surface. “Do you know what this means?” McCallum said to him.

“Yeah, we got the three-hundred-thousand-dollar lander back,” Vescovo said.

“Victor, you have the only vehicle in the world that can get to the bottom of any ocean, anytime, anywhere,” McCallum said. The message sank in. Vescovo had read that the Chinese government has dropped acoustic surveillance devices in and around the Mariana Trench, apparently to spy on U.S. submarines leaving the naval base in Guam; he could damage them. A Soviet nuclear submarine sank in the nineteen-eighties, near the Norwegian coast. Russian and Norwegian scientists have sampled the water inside, and have found that it is highly contaminated. Now Vescovo began to worry that, before long, non-state actors might be able to retrieve and repurpose radioactive materials lying on the seafloor.

“I don’t want to be a Bond villain,” Vescovo told me. But he noted how easy it would be. “You could go around the world with this sub, and put devices on the bottom that are acoustically triggered to cut cables,” he said. “And you short all the stock markets and buy gold, all at the same time. Theoretically, that is possible. Theoretically.”

After a maintenance day, Lahey offered to take John Ramsay to the bottom of the trench. Ramsay was conflicted, but, he said, “there was this sentiment on board that if the designer doesn’t dare get in it then nobody should dare get in it.” He climbed in, and felt uncomfortable the entire way down. “It wasn’t that I actually needed to have a shit, it was this irrational fear of what happens if I do need to have a shit,” he said.

Two days later, Vescovo took Jamieson to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. They returned with one of the deepest rock samples ever collected, after Vescovo crashed into a boulder and a fragment landed in a battery tray.

Buckle started sailing back to Guam, to drop off Walsh, Vescovo, and the Triton crew. “It’s quite mind-blowing, when you sit down and think about it, that, from the dawn of time until this Monday, there were three people who have been down there,” he said. “Then, in the last ten days, we’ve put five more people down there, and it’s not even a big deal.”

The Pressure Drop, anchored in the Svalbard archipelago. The least-known region of the seafloor lies under the Arctic Ocean.

The Pressure Drop, anchored in the Svalbard archipelago. The least-known region of the seafloor lies under the Arctic Ocean.

t was early May, and there was only one ocean left. But the deepest point in the Arctic Ocean was covered by the polar ice cap, and would remain so for several months. The Pressure Drop headed south, toward Tonga, in the South Pacific. Bongiovanni kept the sonar running twenty-four hours a day, and Jamieson carried out the first-ever lander deployments in the San Cristobal and Santa Cruz Trenches. “The amphipod samples are mostly for genetic work, tracking adaptations,” he told me. The same critters were showing up in trenches thousands of miles apart—but aren’t found in shallower waters, elsewhere on the ocean floor. “How the fuck are they going from one to another?”

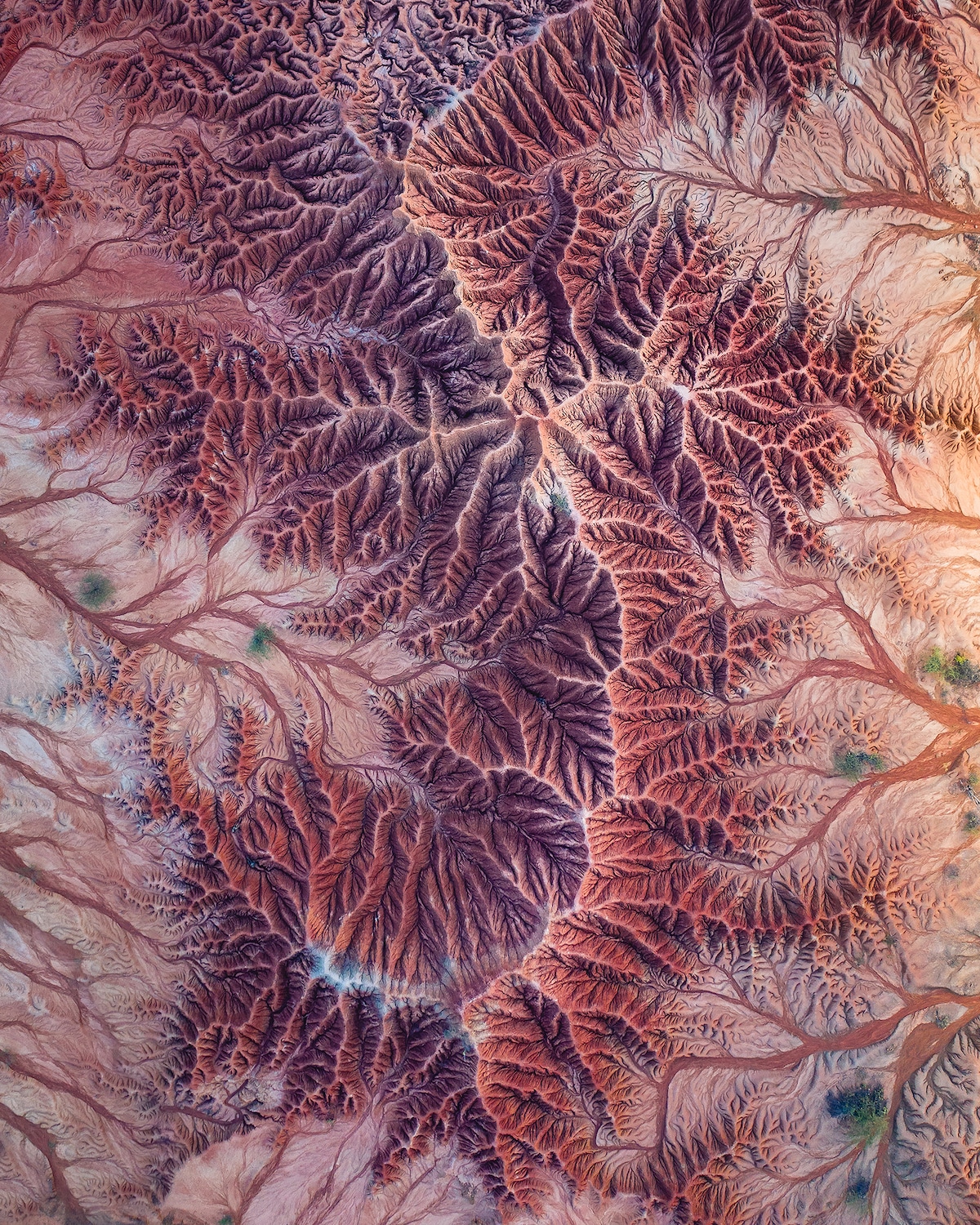

Bongiovanni mapped the Tonga Trench. The sonar image showed a forty-mile line of fault escarpments, a geological feature resulting from the fracturing of an oceanic plate. “It’s horrendously violent, but it’s happening over geological time,” Jamieson explained. “As one of the plates is being pushed down, it’s cracking into these ridges, and these ridges are fucking huge”—a mile and a half, vertical. “If they were on land, they’d be one of the wonders of the world. But, because they’re buried under ten thousand metres of water, they just look like ripples in the ocean floor.”

Bongiovanni routinely stayed up all night, debugging the new software and surveying dive sites, so that the Limiting Factor could be launched at dawn. “Day Forever,” she dated one of her journal entries. “Sonar fucked itself.” Now, before taking leave, she taught Erlend Currie, who had launched Jamieson’s makeshift lander in the Diamantina Fracture Zone, how to operate the EM-124.

“When you give people more responsibility, they either crumble or they bloom, and he blooms,” Buckle said. In the next month, Currie mapped some six thousand nautical miles of the ocean floor, from the Tonga Trench to the Panama Canal. “Erlend’s doing a good job,” another officer reported to Bongiovanni. “He’s starting to really talk like a mapper. He just hasn’t quite learned how to drink like one.”

Iboarded the Pressure Drop in Bermuda, in the middle of July, seven months into the expedition. The crew had just completed another set of dives in the Puerto Rico Trench, to demonstrate the equipment to representatives of the U.S. Navy and to the billionaire and ocean conservationist Ray Dalio. (Dalio owns two Triton submarines.) Vescovo hoped to sell the hadal exploration system for forty-eight million dollars—slightly more than the total cost of the expedition. During one of the demonstrations, a guest engineer began outlining all the ways he would have done it differently. “O.K.,” McCallum said, smiling. “But you didn’t.”

We set off north, through the turquoise waters of the Gulf Stream. It would take roughly three weeks, without stopping, to reach the deepest point in the Arctic Ocean. But the Arctic dive window wouldn’t open for five more weeks, and, as Vescovo put it, “the Titanic is on the way.” For several nights, I stood on the bow, leaning over the edge, mesmerized, as bioluminescent plankton flashed green upon contact with the ship. Above that, blackness, until the horizon, where the millions of stars began. Sometimes there was a crack of lightning in the distance, breaking through dark clouds. But most nights the shape of the Milky Way was so pronounced that in the course of the night you could trace the earth’s rotation.

The air turned foggy and cold. Buckle steered out of the Gulf Stream and into the waters of the North Atlantic, a few hundred miles southeast of the port of St. John’s, Newfoundland. After midnight, everyone gathered on the top deck and downed a shot of whiskey—a toast to the dead. We would reach the site of the Titanic by dawn. At sunrise, we tossed a wreath overboard, and watched it sink.

A few years ago, Peter Coope, Buckle’s chief engineer, was working on a commercial vessel that was affixing an enormous, deepwater anchor to an oil rig off the coast of Indonesia. The chain slipped over the side, dragging down one side of the ship so far that the starboard propeller was in the air. Water poured into the engine room, where Coope worked. It was impossible for him to reach the exit.

British ship engineers wear purple stripes on their epaulets. Many of them think of this as a tribute to the engineers on the Titanic, every one of whom stayed in the engine room and went down with the ship. Now Coope, whose father was also a chief engineer, resolved to do the same. “I saw my life blowing away,” Coope recalled. “People say it flashes in front of you. I was just calm. I felt, That’s it—I’ve gone.” The bridge crew managed to right the ship after he had already accepted his fate.

The next day, Vescovo piloted the Limiting Factor down to the Titanic, with Coope’s epaulets, and those of his father, in the passenger seat. The debris field spans more than half a mile, and is filled with entanglement hazards—loose cables, an overhanging crow’s nest, corroded structures primed to collapse. (“What a rusting heap of shit!” Lahey said. “I don’t want the sub anywhere near that fucking thing!”) Large rusticles flow out from the bow, showing the directions of undersea currents. Intact cabins have been taken over by corals, anemones, and fish.

That evening, Vescovo returned the epaulets, along with a photograph of him holding them at the site of the wreck. Coope, who is sixty-seven, had come out of retirement to join this expedition—his last.

The Pressure Drop continued northeast, past Greenland and Iceland, to a port in Svalbard, an Arctic archipelago about six hundred miles north of Norway. Huge glaciers fill the inlets, and where they have melted they have left behind flattop mountains and slopes, crushed and planed by the weight of the ice. Most of the archipelago is inaccessible, except by snowmobile or boat. The population of polar bears outnumbers that of people, and no one leaves town without a gun.

McCallum brought on board two EYOS colleagues, including a polar guide who could smell and identify the direction of a walrus from a moving ship, several miles away. By now, McCallum had adjusted the expedition schedule ninety-seven times. The Pressure Drop set off northwest, in the direction of the Molloy Hole, the site of the deepest point in the Arctic Ocean. The least-known region of the seafloor lies under the polar ice cap. But scientists have found the fossilized remains of tropical plants; in some past age, the climate was like that of Florida.

It was the height of Arctic summer, and bitterly cold. I stood on the bow, watching Arctic terns and fulmars play in the ship’s draft, and puffins flutter spastically, barely smacking themselves out of the water.

The sun would not set, to disorienting effect. When I met John Ramsay, he explained, with some urgency, that the wider, flatter coffee cups contained a greater volumetric space than the taller, skinnier ones—and that this was an important consideration in weighing the consumption of caffeine against the potential social costs of pouring a second cup from the galley’s single French press.

Ice drifted past; orcas and blue whales, too. Buckle sounded the horn as the ship crossed the eightieth parallel. One night, the horizon turned white, and the polar ice cap slowly came into view. Another night, the ice pilot parked the bow of the ship on an ice floe. The Pressure Drop had completed one and a half laps around the world, to both poles. The bow thruster filled the Arctic silence with a haunting, mechanical groan.

Bongiovanni and her sonar assistants had mapped almost seven hundred thousand square kilometres of the ocean floor, an area about the size of Texas, most of which had never been surveyed. Jamieson had carried out a hundred and three lander deployments, in every major hadal ecosystem. The landers had travelled a combined distance of almost eight hundred miles, vertically, and captured footage of around forty new species. Once, as we were drinking outside, I noticed a stray amphipod dangling from Jamieson’s shoelace. “These little guys are all over the fucking planet,” he said, kicking it off. “Shallower species don’t have that kind of footprint. You’re not going to see that with a zebra or a giraffe.”

The earth is not a perfect sphere; it is smushed in at the poles. For this reason, Vescovo’s journey to the bottom of the Molloy Hole would bring him nine miles closer to the earth’s core than his dives in the Mariana Trench, even though the Molloy is only half the depth from the surface.

On August 29th, Vescovo put on his coveralls and walked out to the aft deck. The ship and submarine crews had so perfected the system of launch and recovery that, even in rough seas, to an outsider it was like watching an industrial ballet. The equipment had not changed since the expedition’s calamitous beginnings—but the people had.

“This is not the end,” Vescovo said, quoting Winston Churchill. “It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

He climbed inside the Limiting Factor. The swimmer closed the hatch. Vescovo turned on the oxygen and the carbon-dioxide scrubbers. “Life support engaged,” he said. “Good to go.”

For the first few hundred feet, he saw jellyfish and krill. Then marine snow. Then nothing.

The Triton crew piled into the control room. Lahey found a box of licorice from Svalbard, took a bite, and passed it around. “Just fucking heinous,” he said, grimacing. “Who the fuck makes candy like that? Tastes like frozen shit.”

There was a blip on the communications system. For a moment, the room went silent, as Vescovo called in to report his heading and depth. Then Kelvin Magee, the shop foreman, walked into the control room.

“Try it, Kelvin, you bastard!” Lahey said. “It’s from Svalbard. It’s local. It’s a fucking Norwegian candy.”

“Get it while there’s still some left!”

“It’s that ammonium chloride that really makes it—and that pork gelatine,” Buckle said.

“Pork genitals?”

McCallum stood quietly in the corner, smiling. “Look at these fucking misfits,” he said. “They just changed the world.”

“Filled with trepidation, we steamed into the teeth of the area where, on the old maps, they used to write, ‘Here Be Monsters,’ ” Vescovo said.

“Filled with trepidation, we steamed into the teeth of the area where, on the old maps, they used to write, ‘Here Be Monsters,’ ” Vescovo said.

Source:The New Yorker

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/05/18/thirty-six-thousand-feet-under-the-sea

“蒂芙尼T代言人”易烊千玺佩戴Tiffany T1系列18K黄金及白金新作,演绎无可T代的摩登魅力

“蒂芙尼T代言人”易烊千玺佩戴Tiffany T1系列18K黄金及白金新作,演绎无可T代的摩登魅力

据朝中社2日报道,顺天磷肥工厂竣工仪式于5月1日举行,朝鲜国务委员会委员长金正恩出席竣工仪式。

据朝中社2日报道,顺天磷肥工厂竣工仪式于5月1日举行,朝鲜国务委员会委员长金正恩出席竣工仪式。